Scoundrels: Chapter 2, Real Estate Is Not the Only Thing for Sale

Monday, December 26, 2016

Each week, GoLocalProv will publish a chapter of the book Scoundrels: Defining Corruption Through Tales of Political Intrigue in Rhode Island, by Paul Caranci and Thomas Blacke.

The book uses several infamous instances of political corruption in Rhode Island to try and define what has not been easily recognized , and has eluded traditional definition.

The book looks at and categorizes various forms of corruption, including both active and passive practices, which have negative and deteriorating affects on the society as a whole.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTBuy the book by CLICKING HERE.

Chapter 2

Real Estate Is Not the Only Thing for Sale

The Saturday morning of February 16, 2002 was fairly cold. For Rhode Island, it was a typical winter day. For Lincoln Administrator, Jonathan F. Oster, it was not that much different than most Saturdays. As he so often did, Oster was heading to his private law office at 1525 Louisquisset Pike. Prior to his election as Town Administrator, Oster spent countless hours at his office meeting with clients and shuffling through papers. By most accounts, he had built a fairly successful law practice. On this particular Saturday he was planning to meet with his old friend and fundraiser, Robert Picerno. But as Oster would soon learn, nothing on this day would be like any other day in his life. Before nightfall, Oster would begin a six-year battle to protect his reputation and preserve his freedom.

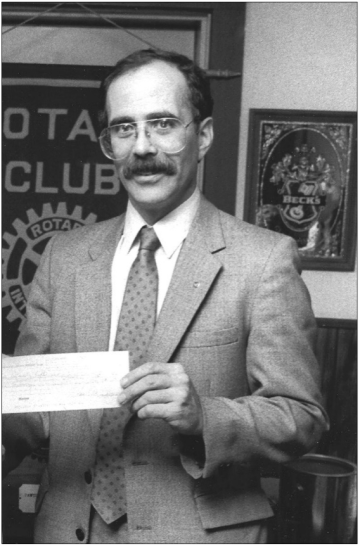

Though Oster had been involved in politics for only a few years, he was no stranger to the game. He grew up in a political environment as his father had served as the town’s very first town administrator. The younger Oster earned his bachelors’ degree at the University of Rhode Island in 1973, his masters from the same school in 1976, and his law degree from Suffolk University in 1981. By 1996 he was a partner in the firm of Oster & Sawyer and was already actively involved in the community having previously served as president of the Cumberland/Lincoln Rotary. He was also a Trustee of the Town’s Land Trust and co-coordinator of the Lincoln Watershed Watch Program. In that year he made his entry into elected politics with a successful run for the Rhode Island State Senate. Already a successful lawyer, Senator-elect Oster, who was married and had two children, was sworn into his first political office in January 1997.

Following two short, relatively uneventful terms in the State Senate, Democrat Oster decided to challenge Republican Burton Stallwood, Lincoln’s Town Administrator since 1972, for the town’s highest elected office. Robert R. Picerno played a key fundraising role in this election. According to Michael Hill, a Cumberland accountant and campaign treasurer for all three of Oster’s election efforts, Picerno raised $10,655, or more than 25% of the $43,284 total that Oster raised in his 2000 run for town administrator.

Oster was a scrappy fighter, and despite long odds, he managed to edge out Stallwood in a tense and hotly contested political battle. The hard feelings created during the election didn’t end on election day, however, and Oster’s planned inauguration was delayed one month, to January 2001, after the State’s highest court granted an injunction that was filed by Stallwood. The two politicians had a dispute over when Stallwood’s term should end and Oster’s begin.

L. Robert Smith, who was recruited by Picerno to do some interim engineering work for the Town’s Planning Board, said Picerno served on Oster’s transition team and helped Oster put his office together in early 2000.

One of Oster’s first acts as town administrator was to pay “almost $1,000 to an electronic surveillance company to scour Town Hall for illegal listening devices. It was a display charged as much with arrogance as paranoia and no bugs were found.” Oster justified his actions at the time by saying, “there ‘were a number of issues that raised the level of concern. There was some behavior going on in office just prior to the other administrator leaving.’ Given that, Oster said, ‘we thought it prudent to conduct a search.”

Perhaps this initial behavior should have been a premonition of things to come. But other than the most vocal of his political opponents, no one really seemed to pay too much attention to his actions. Many politicians understand that the public is apathetic and inattentive. That apathy, in fact, is one of the reasons that corruption flourishes.

Oster settled right in and began addressing several of the routine issues that confront an administrator on a daily basis - examination of expenditures and tax revenues, the appointment of qualified department heads and an evaluation of existing programs and policies.

He also addressed some matters that were not so routine. On January 11, 2001, just days after taking office, Oster’s friend and political confidant, Robert R. Picerno, asked businessman Robert J. Campellone, “if he wanted to buy the H&H Screw Co. property on Route 116” in Lincoln.

The town had taken title to the property in 1991 for taxes owed. No one purchased it at the tax sale because the property was known to have significant environmental problems. The site contained an undetermined amount of industrial waste that an old report issued by the State’s Department of Environmental Management estimated would cost between $400,000 and $2 million to clean up. Although Banneker Industries had occupied the property for the past seven years, they had never paid a penny to the town for rent. When Oster inquired about the arrangement, the once cordial relationship between Banneker and the town soured.

Campellone, an automobile dealer, had known Picerno for at least a year before Oster’s election and the two had developed a close business relationship. In late 1999, Campellone sold Picerno a car that included a free alarm system and a free set of tires. He also included the extended use of his dealer plates. Although only dealership owners, corporate officers or their salespeople normally use dealer plates, state law allows the purchaser of a new vehicle to use them for up to 20 days. This allows a buyer some time to register the car and pay Rhode Island’s 7% sales tax. Allowing Picerno to use the plates for more than a year enabled him to postpone payment of the sales tax on the $22,000 vehicle as well as to avoid payment of the town taxes that would normally have been assessed.

Now Picerno was offering Campellone the H&H property on behalf of the town, a good place Picerno thought, for Campellone to locate his car dealership. However, Campellone was offering only $50,000 for the site, a price that most agreed was too low. Eventually, “Campellone agreed he would pay the town $105,000 for tax title to the six-acre property and pay Picerno $25,000 in cash. Campellone seemed a bit anxious to close the property and take title and was dismayed when he learned that there would be a delay. Responding to Campellone’s question about the timing, Picerno said at one point ‘we can’t move too quickly; my guy’s only been in ten days,’ a reference, Campellone said he assumed, to the recently inaugurated Oster.” Campellone, however, expected that the closing would take place by January’s end.

For Picerno, this might have been the easiest money he ever made. He would soon learn, however, that even easy money takes some work. The deal dragged. Winter turned to spring and still no closing. In June 2001, an impatient Campellone called Oster directly to determine the status of his “bid.” Oster “told him it had to be approved by the Town Council and that Picerno ‘is not lying to you.’ ” During this conversation, Campellone never told Oster that he paid Picerno $25,000 although it is certainly clear that Oster knew of Picerno’s involvement in the transaction. But interestingly enough, after the phone call, the deal started to move along quickly. Picerno brought a letter to Campellone to sign regarding his interest in the property, and Oster prepared tax documents and argued to the Town Council that the deal should be accepted.

But the letter that Picerno and his lawyer, Donald Lembo, presented Campellone with “would create a partnership of him (Campellone), Lembo and Picerno to own the property.” This took Campellone by surprise because he wasn’t looking for partners, especially partners who would not be participating in the financing of the property. Feeling less enthusiastic, but still interested in the deal, Campellone asked his attorney, Joseph DeAngelis, to review the documents. DeAngelis advised Campellone not to proceed, saying of the deal, “it stinks.”

Following his attorney’s advice, Campellone “told Picerno he was out and wanted his bribe back. To convince Picerno to refund it, he told him he had tape-recorded one of their conversations about the payoff.” Not sure that he was telling the truth, but not wanting to chance finding out, Picerno eventually made a partial repayment “with a $15,000 check made out to Campellone from Major Construction Associates, a company doing business with the town. Major Construction is owned by Robert Gelfuso,” someone who would eventually play a prominent role in the transaction.

Around this same time, David Wayne Daniel, a West Warwick contractor, was working to complete his contractual obligations to build a new concession stand and bathhouse, and to make other improvements to the Fairlawn playground in Lincoln. The relatively small job was being paid with a $150,000 federal grant. According to Daniel, “he and his crews were regularly pestered by town officials who complained about the quality and pace of the work. Daniel was also called to three Friday morning meetings in a row in Oster’s office, where the main business, according to Daniel, was ‘jumping on my back.’ ”

While he was berated for the delays, many were not his fault and were certainly not of his doing. One of the problems Daniel encountered was that the playground was located near a wetland requiring a special permit that the town was expected to obtain, but didn’t. At one point, Daniel was told to relocate the bathrooms they were set to build, but the town changed its mind after the hole was dug. Daniel had to bury the hole.

Federal Funds Coordinator, Stephen Balestra, was the most frequent visitor to the construction site. Gelfuso complained that Balestra, along with Picerno, pressured him to inflate his billing statements and kick back the overcharges to them. Parks and Recreation Director Paul Prachniak and Public Works Director David T. Harrison also regularly visited the site. These visits made Daniel nervous but he dealt with it. Then, on the Monday following “the third Friday meeting in Oster’s office, one in which Daniel told Oster that he wanted to be on his team, Planning Board member Picerno showed up at the site. “‘He asked me how things were going and I told him they’re busting my…and he started to laugh a little slyly’ Daniel said. ‘Picerno then took out a pack of 100 Oster fundraiser tickets worth $50 a piece - $5,000 total – and asked if he, Daniel, could take care of them. I said, ‘If you can get those…guys off my back,’ Daniel said he told Picerno. ‘He said, No problem.’ ” Picerno then described the H&H Screw deal in an obvious effort to spark Daniel’s interest.

Rather than paying the full $5,000 requested, Daniel presented Picerno a check for $4,750 “because he had already donated $250 to the Oster campaign, and he didn’t want to double pay.” Picerno wouldn’t accept the check and told Daniel, “I’m going to need it in a nicer way.” Daniel knew that meant he wanted cash, which he later presented to a grateful Picerno.

The name of Daniel’s company was Major Construction Associates and his partner was none other than Robert Gelfuso, the same man that had provided the $15,000 check used by Picerno to partially return the bribe he received from Campellone. Shortly after the playground exchange, the pressure ceased and Oster commended Daniel on a job well done with the site.

Picerno used the Administrator’s office to enhance his own economic status. Many of his actions were self-serving and the more that people visiting Town Hall saw the ease with which he could gain access to the Administrator, the more the perception of his power was exaggerated. He was frequently seen on the rear deck of Town Hall, the deck that “had access to the rest of Town Hall through a sliding door into a conference room that was next to Oster’s private office. It was rarely, if ever, used by the public.”

In 2001, Picerno’s wife Joyce filed suit against the Town of Lincoln “contesting the way the town assessed taxes on the family’s Preakness Drive home. She challenged the method the town used to assess taxes from 1998-2000, refusing to pay about $22,000 in property taxes over those three years, some before Oster took office.” Emerson Johnson, the Tax Assessor at the time, wanted to settle the suit for $11,000, but Oster said he felt comfortable enough in the friendship to convince Picerno to agree to $15,000. According to a secret tape recording of the November 20, 2001 Town Council executive session, Former Assistant Town Solicitor William Dickie suggested that the Council allow Picerno to pay $15,000 of the $22,000 tax bill owed because the $7,000 loss would be less expensive than litigation. The Council voted to support Dickie’s recommendation, but after only a few days, Councilman Dean Lees, Jr., who abstained in the executive session vote, questioned the manner in which the suit was being settled and threatened to contact the state police. It was only after Lees’ threat that Dickie said he conducted additional research and found that the Picernos “hadn’t filed a timely appeal with the assessor, or paid the taxes, both requirements that must be met before a suit can be filed. He said he then recommended that the Council fight the suit.” Regarding the filing of the appeals, Dickie said he relied on the word of the tax assessor. He also said he had assumed that if the taxes had not been paid, the assessor would have informed him of that. However, the law regarding the filing of timely appeals and payment of taxes was contained in the document that Dickie filed before the executive session. Dickie said that the document was boilerplate and that he “hadn’t specifically read the statute the document he filed cited.”

Leon A. “Lee” Blais served Oster from January to June 2001, first as a consultant, then as the Director of Public Works, and eventually as the Assistant Town Administrator. Blais was concerned about more than the perception of power that easy access afforded Picerno. He was uncomfortable from the start that Picerno “seemed to have the run of Town Hall.”

Picerno had served on Oster’s transition team – a position that extended for several months. It is fair to say that the two were very close. Upon taking office, Oster assigned Picerno an office next to his and provided access to what may have been a private entrance in Oster’s personal office. From this vantage point, Picerno interviewed staff personnel and did other work for Oster.

Blais continued to warn Oster about letting Picerno enter into areas of Town Hall that were not accessible to the public. He explained that he was troubled by Picerno’s behavior and recommended that Oster stop associating with him. Despite his warnings, Blais would frequently see Oster and Picerno together at the Lodge, a local tavern frequented by town politicians. One day, while Oster was sitting at the Lodge’s bar Blais approached him. “I basically used a raspy voice and characterized Mr. Picerno as Darth Vader" Blais said. "Oster said he would ‘take steps’ to rein in Picerno, but invariably, Picerno would return.” Oster justified the relationship by telling Blais that Picerno was an integral part of his campaign organization, capable of raising large sums of money and rallying the town’s Italo-American population on his behalf.

But Blais’s fears seemed to be founded in fact. In the fall of 2001, two private citizens, filed two separate state police complaints involving Picerno, alleging “that they had been approached about paying a bribe to a town official.” The subsequent investigation would involve “the first-ever state court authorized wiretap into public corruption.”

At a meeting held on Thursday, February 14, 2002, the state police had the video and audiotape running when David Wayne Daniel and Picerno discussed the details of the bribe payments. Gelfuso was to pay Picerno $25,000 for the tax title document that would allow Daniel and his partner to take over the land.

Wired for sound by the state police, Gelfuso did meet with Picerno at Stuffie’s Restaurant in North Providence. Police took photographs as Gelfuso handed over a bulging envelope containing a $5,000 partial payment to Picerno when the two were in the parking lot.

But the payment plan morphed several times. During a taped conversation that took place on December 4, 2001, Picerno suggested that instead of cash, Picerno could pay Gelfuso $75,000 for a piece of property worth $100,000. Daniel would make a payment of $15,000 to cover legal fees. He would also pay the town $105,000 as a purchase price for the property. “There were no formal names in Picerno’s patter; it was ‘Frankie’ and ‘Bobby.’ ‘Fifty green’ was $50,000. He would hint and imply, using phrases like – ‘you know what I’m saying?’ – rather than say things directly. And there were repeated hints at nebulous future deals.”

At the time of this meeting, Picerno was serving on the Lincoln Planning Board, a body that was able to determine the fortunes of a developer with a “yes” or “no” vote. During the session, Picerno alluded to future deals, spoke of lessons from prior dealings and boasted of his clout while talking about failed deals that he could have saved. They also spoke of potential tenants for the property. They included Campellone’s car dealership and a 7-Eleven store that Campellone had talked about building. Picerno told Daniel he could match or pay 10% more than what another contractor could do.

On Friday, February 15, 2002, Gelfuso met with Picerno and delivered the $20,000 bribe balance for the purchase of the H&H property. The payment was made with money that the state police had convinced Citizen’s Bank to provide through a cooperative agreement with the bank. Citizen’s also provided a phony bank check made out to the Town of Lincoln for $105,000 as the agreed upon payment for the land.

Following that meeting, Campellone was arrested and charged with bribery. He entered a guilty plea and was offered a five-year deferred sentence in exchange for his cooperation against Oster and Picerno.

So, on that cold, winter, Saturday morning of February 16, 2002, Oster and Picerno met for almost an hour. Oster had no way of knowing that Picerno, who had already been arrested on February 14th, was also wearing a police wire. “The meeting started in Oster’s office, but moved outside after he told Picerno about how lawyers’ offices can be bugged by law enforcement. While they are outside, Oster told Picerno that Gelfuso had been talking to state police, accusing Picerno of extorting money from Gelfuso’s partner Daniel in exchange for getting town inspectors to ease up on their inspections of a job site the contractors had in town.” The police also videotaped a portion of the meeting that took place outside the law office. During the meeting, Picerno put an envelope with $10,000 in $100 bills “in a metal mailbox, saying “’All right, that’s from Wayne, for that H&H [expletive].’ The envelope with the cash was found in Oster’s office later in the day when police searched it.”

A few hours after their meeting ended, Oster was arrested and charged with two counts of bribery and two counts of conspiracy. His six-year legal odyssey was just beginning. The bribery charges alone could bring a jail term of up to 40 years and fines of up to $100,000.

Oster was quick to proclaim his innocence saying that he would stay in office and fight the bribery charges. His critics were just as quick to call for his resignation. On February 17th, just one day after his arrest, several town officials said that Oster should resign his elected position immediately. “Several questioned whether he could effectively govern the town and whether his continued presence would tarnish Lincoln’s generally positive image. ‘Should he continue? Given these charges, I say no,’ said Town Council President Raymond Dapault,’ ” Just a week earlier, Depault had announced his intention to oppose Oster in the 2002 Democrat primary.

Even Oster’s strong supporters, such as Democrat Councilman Dennis Auclair, agreed that Oster would probably have to resign. Republican Burt Stallwood, whom Oster had taken down in the election of 2000, said, “‘it’s a big disappointment. The town was always considered one of the best-run in the state.’ Noting that his predecessor, Barry J. Farrands, was convicted soon after leaving office, Stallwood said, ‘This turns the clock back 30 years.’ ” Ironically, Stallwood had just been appointed U.S. Marshal.

Jonathan Oster was arrested by state police on February 16, 2002 and charged with two counts of bribery and two counts of conspiracy.

Councilman Dean Lees, Jr., a long-time Oster critic promised court action to prevent Oster from entering Town Hall if he did not resign. He added that the news didn’t surprise him because of “what he perceives to be the administration’s ‘numerous charter and ordinance violations since coming to office.’ ”

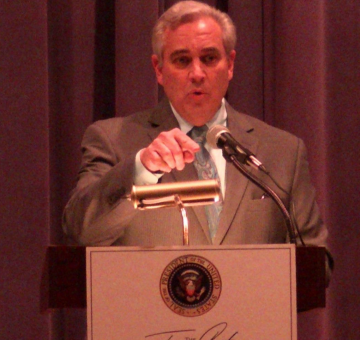

Attorney General Sheldon Whitehouse, who at the time was a candidate for Governor and has since gone on to the United States Senate, said of the case, “Rhode Island residents, who pay some of the highest local taxes in the nation, deserve to be protected by aggressive efforts to root out corruption. Such corruption drives up the cost of services, scares off business and fuels apathy and cynicism, poisoning a system of local government that thrives on citizen involvement. Municipal officials must get the message that the law is watching, and that they face serious trouble if they condone corruption or accept bribes in the course of their official business.”

On February 19, 2002, Oster told reporters that he was innocent of the charges against him. Speaking outside Town Hall Oster said, “I am going to have an opportunity to prove that in court. I have no further comment until then. As any other innocent individual, I’m coming to work to do my job as I was elected to do by the people of the town of Lincoln. I fully intend to fulfill my functions at my job. Thank you very much.”

The Town Council was unmoved. That same night they voted unanimously to ask Jon Oster to resign his office. Oster, who is required under the Town Charter to attend all council meetings, did not show up despite having reported to work that day. The Council passed a second resolution asking lawyers to draft a complaint to the State Ethics Commission, a body that has the legal authority to remove Oster from office, a power that the council did not have. Finally, the council voted to hire an independent counsel to review every transaction the town undertook during Oster’s term of office.

Over the course of the next month, several town officials were subpoenaed to appear before a statewide grand jury called to investigate government corruption in Lincoln. Investigators also subpoenaed municipal records from several different departments of town government and state police questioned several key town officials.

In 2004, the Picerno and Oster cases were separated. Picerno pleaded no contest to four counts of soliciting bribes and three counts of conspiracy to solicit bribes. He was sentenced to eight years, three to serve, at the Adult Correctional Institution (ACI) in Cranston, Rhode Island.

Over the next several years, lawyers wrangled over legal motions. Motions to exclude certain evidence from trial and motions to prohibit certain witnesses from testifying. One motion was to suppress evidence obtained through what was alleged to be an unlawful search and seizure that turned up four guns, a .380-caliber handgun, an Ingram 9mm\.45-caliber Mac 10 automatic machine gun, a 12-gauge shotgun and a .22 caliber rifle that were found in Oster’s office. Finally, “after several years of pretrial appeals over admissibility of evidence and trial procedure that included an appeal to the state Supreme Court, Oster’s trial was scheduled to begin in early January 2008.”

Part of the defense strategy became apparent even in pretrial hearings. Clearly, the strategy would be to “attack the credibility of Picerno. Oster’s lawyer, C. Leonard O’Brien, called Picerno a liar at more than one pre-trial hearing and in late November 2007 used a disclosure request to try to further tarnish the reputation of what he called the state’s core witness. He asked the judge to order the state to specify what Picerno would be testifying to during the trial, saying Picerno had given differing accounts of some events in police interviews and during other hearings.”

In January 2008 Superior Court Associate Justice Gilbert V. Indeglia issued his final pre-trial motion ruling paving the way for the long awaited trial to begin. But on February 5, 2008, just 3 days after it began, the trial came to a halt again as two jurors came down with the stomach flu. The one-day delay didn’t seem to disrupt the state’s momentum, however, as the jury heard damaging testimony against Oster for several consecutive days.

Finally, on February 19, 2008, the 12-member jury was ready to begin deliberating “on whether ex-Lincoln Town Administrator Jonathon F. Oster is guilty of bribery and conspiracy or just bad judgment in his choice of friends.” But first, Judge Indeglia explained to the jurors “that if a criminal conspiracy existed, that in itself is a crime. The state wouldn’t have to prove a bribe was ever paid, only that Picerno and Oster schemed to get it. All members of a conspiracy are culpable for the acts of other conspirators whether they knew what they were doing or not. One conspirator could even order another not to commit a specific crime, but if the other did it anyway, both are equally liable.”

On Thursday, February 21, 2008, little more than two days into their deliberations, the jury returned, and, “After listening to a case that relied heavily on tapes of Picerno’s conversations with bribery targets and with Oster, found the former state senator guilty of two counts of bribery and two counts of extortion for actions he took while town administrator from 2000 – 2002.”

Judge Indeglia set Oster’s sentencing for May 8, 2008. At that time, he would be allowed to sentence Oster to a maximum of 20 years in prison on each bribery charge, and 10 years on each conspiracy count; a total of 60 years. Oster’s attorney, C. Leonard O’Brien immediately promised an appeal and Oster was released pending sentencing.

Friday morning, less than a day after his guilty verdict, 56-year old Oster drove to his Louisquisset Pike law office just as he did on most other days. He entered his second floor office at about 7:00 A.M., the same office where his friend, Robert Picerno, had betrayed him 6 years earlier. He walked into the conference room, held a gun to his head and pulled the trigger.

Oster’s suicide stunned the community – maybe as much as the charges against him and the guilty verdict did. “Attorney General Patrick C. Lynch, whose office had won the conviction, said, ‘this is a tragedy upon a tragedy and, obviously, a heartbreaking loss for Mr. Oster’s family and loved ones. I offer them our sincerest sympathies.” Many other elected officials expressed shock and spoke of better days with their friend Jonathon Oster.

The suicide had a devastating impact on the jurors as well. Noting that, “he could not recall a case where a defendant killed himself so soon after a verdict,” Superior Court Presiding Justice Joseph F. Rodgers, Jr. offered all 12 jurors and 4 alternates counseling with a specialist with the RI Critical Incident Stress Management Team. At least 14 of the 16 jurors took advantage of the offer as did Judge Indeglia, defense attorney Bethany Macktaz, prosecuting attorney William Ferland and Attorney General Patrick Lynch.

The entire tragedy that is the story of Jonathan Oster was to have one more ironic twist of legal fate. As a result of a unique Rhode Island statute, a convicted person who dies prior to sentencing is considered to have died without guilt. Guilt, in other words, is conferred only upon completion of sentence imposition by a judge. In that sense, Jonathan Oster, having been lawfully convicted by a jury of his peers on all four felony counts charged against him, left this world one day after his conviction, an innocent man.

Paul F. Caranci is a historian and serves on the board of directors for the RI Heritage Hall of Fame. He is a cofounder of, and consultant to The Municipal Heritage Group and the author of five published books including two produced by The History Press. North Providence: A History & The People Who Shaped It (2012) and The Hanging & Redemption of John Gordon: The True Story of Rhode Island’s Last Execution (2013) that was selected by The Providence Journal as one of the top five non-fiction books of 2013. Paul served for eight years as Rhode Island’s Deputy Secretary of State and for almost seventeen years as a councilman in his hometown of North Providence. He is married to his high school sweetheart, Margie. They have two adult children, Heather and Matthew, and four grandsons, Matthew Jr., Jacob, Vincent and Casey.

Thomas Blacke has devoted his life to marketing, media and public relations and currently runs his own marketing, PR and security consulting firm. He has worked on many high level political campaigns, served as a lobbyist, and has held leadership positions in the local Democrat Party. Thom is also a professional magician and escape artist who holds multiple Guinness® World Records for escape artistry with ten world records in all. Blacke is the Editor/Publisher of an international magazine and the co-creator of a TV reality show. This is his seventh book.

Related Slideshow: Rhode Island’s History of Political Corruption

Related Articles

- “Scoundrels” Introducing Paul Caranci and Thomas Black’s Book on RI Political Corruption

- Scoundrels: Chapter 1, Bugs in City Hall

- NEW: Central Falls’ Mayor Unveils Plan to Tackle Corruption

- State Report: Medical Pot, Central Falls Corruption & Educating Poll Workers

- The Scoop: Candidate Levies Corruption Charge Against Taveras

- Timeline of Events in Providence Scrap Metal Corruption Lawsuit

- Rhode Island’s Biggest Political Corruption in Modern History

- NEW: Former Central Falls Mayor Pleads Guilty to Corruption Charges

- NEW: Moreau Pleads Guilty to Federal Corruption Charges

- Travis Rowley: Crowley’s Corruption, Not Flanders’ Folly

- Special 920 WHJJ Radio Report: Corruption in Providence

- Podcast: Corrente on Corruption in PVD Play Download

- GoLocalTV: Collins Takes On Big Government, Corruption

- Block Calls for End of Political Corruption in Rhode Island

- RI Corruption Topped National News 20 Years Ago: What’s Changed?

- Moore: Only Voters Can Stifle RI Corruption

- Cheat Sheet 49, FBI Files: Las Vegas Casinos, RI Corruption, Callei Murder, Bonded Vault

- Bob Whitcomb’s Digital Diary: 38 Studios is More Sloth and Stupidity than Corruption

- Raimondo’s Preferred Hedge Fund is About to Plead Guilty to Federal Corruption Charges, Say Reports