Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 40

Monday, December 07, 2015

Between 1986 and 2006, Rhode Island ran a gauntlet of scandals that exposed corruption and aroused public rage. Protesters marched on the State House. Coalitions formed to fight for systemic changes. Under intense public pressure, lawmakers enacted historic laws and allowed voters to amend defects in the state’s constitution.

Since colonial times, the legislature had controlled state government. Governors were barred from making many executive appointments, and judges could never forget that on a single day in 1935 the General Assembly sacked the entire Supreme Court.

Without constitutional checks and balances, citizens suffered under single party control. Republicans ruled during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; Democrats held sway from the 1930s into the twenty-first century. In their eras of unchecked control, both parties became corrupt.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTH Philip West's SECRETS & SCANDALS tells the inside story of events that shook Rhode Island’s culture of corruption, gave birth to the nation’s strongest ethics commission, and finally brought separation of powers in 2004. No single leader, no political party, no organization could have converted betrayals of public trust into historic reforms. But when citizen coalitions worked with dedicated public officials to address systemic failures, government changed.

Three times—in 2002, 2008, and 2013—Chicago’s Better Government Association has scored state laws that promote integrity, accountability, and government transparency. In 50-state rankings, Rhode Island ranked second twice and first in 2013—largely because of reforms reported in SECRETS & SCANDALS.

Each week, GoLocalProv will be running a chapter from SECRETS & SCANDALS: Reforming Rhode Island, 1986-2006, which chronicles major government reforms that took place during H. Philip West's years as executive director of Common Cause of Rhode Island. The book is available from the local bookstores found HERE.

Part 4

40

Redistricting Revenge (2000–02)

Redistricting may be the deadliest political weapon — and the one that voters understand least. The U.S. Constitution assigns state legislatures responsibility for Congressional elections, and state constitutions require the redrawing of legislative and congressional districts every decade. But state legislative leaders often manipulate the mapping process for partisan advantage or to cull mavericks. Redistricting rewards allies, demolishes enemies, and drives American politics.

Devious redistricting began with America’s founders. Elbridge Gerry, who signed the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation, became governor of Massachusetts in 1810. In 1812, Gerry oversaw the redrawing of state senate districts that packed Federalist voters into a contorted district that allowed his Democratic-Republicans to win extra seats in the surrounding districts. Though Gerry despised partisanship, he signed the new districts into law.

The Federalists felt cheated, and the editor of their newspaper, the Boston Gazette, likened the bizarre district to a salamander. A cartoonist added wings to create the dragon that merged Gerry’s name into a new word that functioned as either a noun or verb: “gerrymander.”

Exactly 170 years later, Rhode Island Senate Majority Leader Rocco A. Quattrocchi and his backers, nicknamed “Rocco’s Robots,” gerrymandered Senate Minority Leader Lila M. Sapinsley and maverick Democrat Richard A. Licht into a single district on the East Side of Providence. No matter which one lost, Quattrocchi expected to eliminate one troublemaker, but his gerrymandering ravaged neighborhoods and provoked lawsuits in both state and federal courts.

On June 3, 1982, Superior Court Judge James Bulman struck down Quattrocchi’s Senate maps for violating constitutional standards of compactness and diluting the African-American vote.

Too late to redraw districts before the 1982 election, the General Assembly revived the decade-old Senate districts, and Republicans promptly sued in U.S. District Court.

In February 1983, Senior U.S. District Judge Raymond J. Pettine ruled that Quattrocchi’s gerrymanders violated the one-person, one-vote principle established by the U.S. Supreme Court. Pettine ordered that new districts be drawn for a special Senate election that June. Beyond holding over a lame duck Senate, the debacle wasted $1.5 million in tax dollars.

Payback came in the June special election. Voters tripled the number of Republican senators to twenty-one. The surviving Democrats ousted Quattrocchi from his post.

In a defensive interview, he told the Providence Journal: “I didn’t rob a bank, I didn’t kill anyone. If I did, it would be justified. But I treated all those people fairly.” Ironically, Quattrocchi’s heavy-handed redistricting empowered the very mavericks he meant to harm. Public support prompted both Sapinsley and Licht to run for lieutenant governor, ironically against each other. In the 1984 statewide election, Licht won by less than one percent.

Since the Bloodless Revolution of 1935, factions of Democrats had often battled for control of the General Assembly. Leadership contests resembled family feuds more than policy debates. After the 1988 election, two Democrats — David R. Carlin Jr. and John J. Bevilacqua, son of the former chief justice — had battled to lead the state Senate. Carlin won a narrow majority among Democrats and became majority leader, but Bevilacqua forged an alliance with Minority Leader Robert D. Goldberg that gave him de facto control. Goldberg reaped his reward when his wife, Maureen McKenna Goldberg, vaulted from serving as the Westerly town solicitor to a Superior Court judgeship.

In 1990, after a majority of Democrats chose John Bevilacqua as their leader, some Carlin supporters — particularly East Providence Sen. William V. Irons — kept railing against him. In November 1992, Bevilacqua allies lost to Republican challengers in four key races, which shifted the balance again, and Senate Democrats elected North Smithfield Sen. Paul S. Kelly as majority leader. Bevilacqua loyalists lost their committee leadership positions, offices, and prime parking places.

Although Bevilacqua chose not to seek re-election in 1994, survivors from his faction remained at odds with Kelly’s troops through several election cycles. As the 2000 legislative session ended, the Senate seethed with caustic comments, hostile glances, and clenched jaws. One afternoon, I bounded up a zigzagging back stairway and crashed a furtive huddle of senators who had been Bevilacqua stalwarts. Too late to turn away, I made a joke. “Sorry,” I said, “is this your office now?”

Sen. Stephen Alves shifted position to let me pass. “It’s all we’ve got,” he quipped, “at least for now.”

Barely two weeks after the session ended, smoke cleared from the battlefield. One of Majority Leader Paul S. Kelly’s long-time supporters, East Providence Sen. William V. Irons, launched a hostile take-over. Though he had long been Bevilacqua’s implacable foe, Irons now formed an alliance with Bevilacqua survivors and made no secret of his ambition. “This is not about Paul Kelly,” he told reporter Christopher Rowland. “It’s about me wanting my opportunity.”

In a legislature where the pivotal battles involved factions of Democrats, Irons and Kelly targeted the all-important September 12 primary election. Each recruited surrogates, helping them with money and expertise. On primary night, four of Irons’ candidates defeated Kelly backers. “With tonight’s elections,” Irons declared, “the tide has turned. The momentum is now in our camp.”

One contest had racial overtones. Irons backed incumbent Robert T. Kells, a Providence police lieutenant and former Bevilacqua ally who was white, against Juan M. Pichardo, a Latino challenger supported by Kelly. Kells won by 94 out of 2,466 votes cast. Late in September, Irons snagged Kelly’s Deputy Majority Whip Thomas R. Coderre, and the contest ended. Other senators fell into line. “I almost felt like I had swallowed a bowling ball when I had to make the decision,” Woonsocket Sen. Marc A. Cote told a reporter. “That’s the way the dynamics of leadership politics takes place.”

Well before the November 2000 election it became obvious that Irons would lead the Senate. The question remained: in the redistricting soon to begin, how would Irons treat Kelly and the fifteen senators who stuck with him?

Since the 1980s, Common Cause had promoted rules that would make redistricting independent, fair, and open, but we achieved little. For the 2001–02 remapping, we set out to build a coalition that could expose gerrymanders and discourage the manipulation of racial minorities. We began meeting with civil rights leaders, community organizers, lawyers, and clergy. Most were amazed at the maps from 1991–92, where — like fossils in layers of shale — the gerrymandered districts were obvious.

Leaders of the Urban League and the NAACP had challenged racial gerrymanders in the 1982 Senate plan and eventually prevailed in federal court. From that victory came new Senate districts and the special 1983 election in which Charles D. Walton became Rhode Island’s first African-American state senator.

At the Urban League’s squat, fortress-like headquarters on Prairie Avenue, I unrolled maps for executive director Dennis B. Langley and several staff members. “Our community knows both the pitfalls and the promise of redistricting,” Langley said with a soft Caribbean inflection. “The influx of Latinos creates a new dynamic that we need to handle with great care.” He asked who might lead a coalition to fight for fair redistricting.

I suggested Angel Taveras, a young Latino lawyer who had gone from public schools in South Providence to Harvard University and Georgetown Law School. At twenty-nine, Taveras had run a credible campaign for Congress in the 2nd District, winning hundreds of votes in white suburbs and villages across South County. In Providence, he ran a close second behind incumbent Congressman Jim Langevin.

A week later, Angel Taveras sat with his back to a glass wall in a conference room at Brown Rudnick, the Providence law firm. Behind and below him lay a patchwork quilt of historic houses. “Why me?” he asked with a smile. “You’re not even letting me catch my breath.”

I talked about his personal biography and influence in the Latino community. I said the coalition would need his intellect and skills.

Slim and geeky behind rimless glasses, he was not eager. “Why not Juan Pichardo?” he asked.

I said Pichardo had been aligned with Paul Kelly in 2000 and planned to run again in 2002. “Part of our job will be to prevent the drawing of districts that pit blacks against Latinos on the South Side.”

“What would you want me to do?”

“Lead the coalition,” I said. “I’d be glad to serve as secretary and do a lot of the legwork. We can run it out of the Common Cause office, but you would be the coalition’s face and voice.”

“Let me read these materials,” he said. “It’s a highly specialized area of the law. I’ve never done this work or read the Supreme Court cases.”

On a bitter December night, I made my way along the side of a huge church, up steep stairs into a former convent that was now home to Progreso Latino, the leading social services agency in Central Falls. Tomás Avila, its executive director, invited the dozen visitors around a square of tables to introduce ourselves.

Patrick Tengwall described the Urban League’s work in previous rounds of redistricting. “We’ve seen huge changes in technology,” he said, “but redistricting remains the ultimate insiders’ game. It will take strong voices to protect our communities.”

Nancy Rhodes introduced herself as president of Common Cause. “I don’t know the technicalities, but I know the only way we can get this right is by working together.”

Next to her was Joe Buchanan, a burly community activist from South Providence. “I represent the black community and the Green Party,” he began. “I don’t know about this computer stuff, but I know the way they’ve messed with black people’s lives, and I don’t like it.” He brought down a massive fist next to Rhodes’ elbow, but she did not flinch.

“I know my community,” he rumbled on. “Black people have been here a long time. When people see new minorities coming in, it pits minority against minority. I’m mad about our always getting the crumbs, and I’m ready to do anything it takes. Anything.”

Next in line was Joseph T. Fowlkes, a former professional football player who now headed the Providence NAACP and an umbrella group called the Civil Rights Roundtable. Fowlkes laid a large hand on Buchanan’s arm. “I understand Joe Buchanan’s anger,” he said gently, “and I want to make sure we address these most basic issues of community representation.”

Tony Affigne, a professor at Providence College and a leader in the Green Party, worried aloud about the danger of conflict between the African-American and Latino communities. “We need solutions that both communities perceive as fair. The problem is that there is no preprinted definition of fair. Fair is what we negotiate.”

Angel Taveras arrived as the introductions ended. “Angel Taveras,” he said simply and sat down.

I projected acetate transparencies of gerrymanders that legislative leaders had proposed in ten years earlier. Under public pressure, they had retreated from the most egregious, but improvements in computers and software had vastly increased their ability to protect incumbents. Shapes of districts could be shifted with the click of a mouse. Their database contained income levels, race, and voting patterns. Any change in the lines instantly produced new data calculations. Within months the General Assembly would pass enabling legislation, create a redistricting commission, and appoint its members.

We appointed working groups and scheduled a larger coalition meeting in January. One group would propose ways to lessen tensions between blacks and Latinos in Rhode Island’s cities; another would reach out to organizations we hoped would join; a third would draft legislation to introduce in the General Assembly. Angel Taveras agreed to serve as temporary chairperson. He closed with a warning that the districts drawn in 2001 would shape political life for the next decade. “Even with the holidays,” he said, “we have a lot of work to do before our next meeting. If we don’t set the agenda, others will set it for us.”

Our next meeting took place on a January night with sleet splattering in windy gusts against the windows at the Urban League. Taveras congratulated coalition leaders who made it through the storm. “If this is the worst we face, we’ll be in great shape,” he said cheerfully. I thought everyone understood English, but he paused to translate into Spanish.

“When you study our legislation tonight,” he went on, “its elements may look technical but you can summarize them in three words. Every time you boot your computer, three letters pop up on your screen: DOS. Let DOS remind you what we demand: Diversity, Openness, Standards.”

Joseph M. Fernandez passed out photocopies of the draft legislation. A son of Philippine immigrants and now in his mid-thirties, Fernandez had graduated from Harvard Law School. “Everything we want is fair and reasonable,” he began with a smile. “We may not get all we ask for, but this legislation gives us the high ground to plant our flag.” Fernandez proposed standards for mapmakers: districts must, wherever possible, conform to existing municipal boundaries; and no district should dilute the representation of communities that were identifiable by race or national origin.

“I think,” said ACLU director Steve Brown, “that we need to add an explicit requirement that would say something like: ‘In compliance with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, no district shall dilute the representation of communities that are identifiable by race or national origin.’”

“Absolutely.” Fernandez noted the suggestion in his draft, then moved on. “Here’s the standard they’re most likely to resist: ‘The places of residence of incumbents or candidates shall not be identified or considered.’”

“No kidding!” Joe Fowlkes peered over his text at Fernandez. “They are not going to like this one bit.”

“It’s the key,” Fernandez replied. “Without it, they win.”

The most radical section spelled out appointments to the redistricting commission. “In the past,” Fernandez said, “House and Senate leaders appointed all members of redistricting commissions. Our drafting committee proposes to divide and spread that appointing power. We would argue that a broad range of appointing authorities produces a more responsible body.” The legislation listed elected officials who would choose commissioners. General Assembly leaders would appoint eight of thirteen members, but the governor and the four members of Rhode Island’s congressional delegation would appoint five others. On that rainy winter night no one believed we could wrestle even five of thirteen appointments away from General Assembly leaders, but we agreed to try.

Within a few weeks twenty-six grassroots groups joined what we began calling the Fair Redistricting Coalition.

Finding sponsors was a struggle. Senators and representatives skimmed the text of our bill and raised their eyebrows. A few who had supported William V. Irons over Paul Kelly for majority leader took copies to review, and I knew they would show him. In the days that followed, several said they had decided to co-sign legislation Irons would introduce.

Senators who had stood with Paul Kelly in the leadership fight clearly understood what they risked with the Fair Redistricting Coalition’s bill. “No offense,” said Sen. Charles D. Walton, the state’s only African-American senator. “If you can find someone else to lead, that would be better.” The Providence waterfront limited how far east his South Providence district could go, and preliminary census figures showed a huge influx of Latinos across Broad Street to the west. “If you can’t find someone else,” he offered, “come back to me.”

Sen. Mike Lenihan welcomed me to the tiny office he got after Irons ousted him from chairing the Senate Finance Committee. In the previous redistricting, Bevilacqua’s commissioners gave him a district that wrapped around another they chose to protect. Lenihan looked up from our redistricting bill and drew a long breath. “Do you know what you’re asking?”

“Probably not as well as you,” I said. “What will this cost you?”

“With Billy Irons running the Senate, I’m never quite sure.”

“So is that a yes or no?”

“If you can’t find anyone else, it’s an extremely reluctant maybe.”

On the House side, Rep. Joseph S. Almeida, who headed the Black Caucus of State Legislators, was less anxious. “Understand I’m not saying this will pass,” Almeida said. “But we might get some provisions into the final bill.”

Word from the tiny House Republican Caucus was that several would sign as co-sponsors and that they would speak at a press conference where we would unveil the bill.

But unpleasant surprises came quickly. First was a furtive word from one of the thirteen House Republicans that House Minority Leader Robert A. Watson had changed his mind. “That’s my prerogative,” Watson declared as I sat in his first floor office. “We’re filing our own bill tomorrow.”

“You know it’ll never pass,” I said.

“Neither will yours,” he shot back. A bust of Abraham Lincoln sat on the bookcase behind him. Outside his window, heavy snow fell, blotting out sounds of traffic on Smith Street.

“We were hoping for a bipartisan counterforce to Harwood’s juggernaut,” I said.

“I don’t think you’ll have any House Republicans on your bill.”

The second shock came when Joe Almeida failed to appear for a 3 o’clock press conference called to announce the Fair Redistricting Coalition’s bills. We waited fifteen minutes and finally began without him.

Sen. Mike Lenihan walked reporters through his Senate bill. A broad range of elected officials would appoint the commission; redistricting commissioners must stay at arms’ length from the General Assembly; numerous public hearings would inform communities; and clear legal standards would make it difficult to “pack or crack” communities into weirdly shaped districts. Lenihan coined a phrase for the difficulty and danger of this effort. He said, “I liken it to carrying a handful of balloons through a roomful of cacti.”

Later that afternoon, I entered the Senate chamber and saw senators, staff, and lobbyists clustered at the left side, studiously ignoring a scene that instantly made my face burn. With his back toward me, Irons excoriated Lenihan, who sat in his high-backed seat facing the diatribe. Lenihan said nothing, maintained eye contact, and let the smaller man’s petulance run its course.

Our press conference landed on the front page of papers across the state: “Forget about the shape of the state’s new political districts,” wrote Ariel Sabar in the Providence Journal. He described the opening skirmish as a “quarrel over whether the bargaining table should be octagonal or oval.” Our bill brought “a first whiff of gun smoke in a battle where no detail is too small to fight over and no one has delusions of an easy victory.”

I knew from talking with Almeida several times in January that he supported the Fair Redistricting Coalition’s principles. When I asked why he missed the press conference, he mumbled excuses. There was no need to tell me that Harwood had pressured him. I had badly underestimated the heat that he and Lenihan would take for putting our proposals in play.

The U.S. Supreme Court and many state courts viewed legislative redistricting as an inherently political process, and only a handful of state legislatures had ever relinquished control. In 1980, Iowa established a nonpartisan process for redrawing its congressional and state legislative districts in accord with strict criteria. The law declared that those drawing the maps could not consider the addresses of incumbents or candidates. Previous election results were also out of bounds. Redistricting plans went to public hearings and then a vote in the legislature, where lawmakers could not change the panel’s plan, only vote it up or down. If they rejected a plan, they would get a second plan that they could approve or reject but not amend. In contrast to Iowa, Rhode Island seemed paternal, petty, and profligate.

In a Machiavellian move, legislative leaders asked individual representatives to draw the districts they preferred. For loyalists they chose to protect, that would be easy. But how should those at odds with their leaders respond? Should they reveal their ideal districts or offer a ruse?

Three weeks after he upbraided Mike Lenihan for sponsoring the Fair Redistricting Coalition’s proposal, Senate Majority Leader Bill Irons filed his own bill. A quick reading made me think Irons had studied our bill and deliberately tacked in the opposite direction. He followed previous redistricting laws in having legislative leaders appoint the entire commission. There were no restrictions as to whom could be appointed: lobbyists and political hacks would be welcome, along with community people House and Senate leaders felt they could control.

Nor would Irons allow Rhode Island’s Republican governor or four Democratic members of Congress to make any appointments.

Where the Fair Redistricting Coalition’s bill called for districts to stay within municipal boundaries and geographic barriers wherever possible, Irons declared that districts should “reflect natural, historical, geographical and municipal and other political lines, as well as the right of all Rhode Islanders to fair representation and equal access to the political process.” His laundry list of vague standards would legitimize oddly drawn or distorted maps.

The Irons bill also ignored the coalition’s requirement that mapmakers not identify or consider the residences of incumbents and candidates. Without that restriction, mapmakers could slip incumbents or challengers into districts they were bound to lose; maps could exclude incumbents from districts they had served or challengers from districts where they planned to run. During the 1991–92 round of redistricting, Irons had protested vehemently when Bevilacqua’s forces tabled a Common Cause amendment to create a nonpartisan redistricting commission. He raged when the Bevilacqua panel gerrymandered his East Providence district. Now he copied those rules he had once condemned. Irons’s bill would empower him to control the commission and bend boundaries to suit his strategic interests.

The census bureau reported in March 2001 that Rhode Island’s Hispanic population had doubled since the 1990 count and produced a net growth in the state’s population. The capital city — now thirty percent Latino — showed more population growth in the 1990s than in any other decade since European immigrants swelled the count in 1910. The census confirmed what people on the city’s South Side already knew: Broad Street had filled with bodegas, jewelry shops, and car repair businesses that flew Dominican flags. Pawtucket, Central Falls, and Woonsocket experienced similar surges, mostly from the Dominican Republic, Colombia, and Guatemala.

A notable rise in non-Hispanic populations had occurred west of Narragansett Bay, where Washington County grew 12.3 percent. In Kent County, rural West Greenwich almost doubled in population as developers carved new neighborhoods out of forest and farmland — most with quaint names like Arcadia Farms, West Country Farms, and Wickaboxet Hills. Meanwhile seven cities or towns had lost population. Newport and Middletown, where Navy cuts had taken a toll, lost most. These changes would shift the shapes of East Bay districts.

Angel Taveras phoned me at Common Cause, speaking so softly that traffic noise almost blotted him out. House Majority Leader Gerry Martineau had called him. “Martineau says he’s handling redistricting for the speaker. He said they haven’t picked all the members of the commission, but they want me to serve.”

“That sounds positive.”

“That’s what I thought,” Taveras replied. “I told him that after the legislation passes, I would consider an appointment. Until then I would continue with the coalition. That didn’t seem to bother him.”

“Any compromise on elements of our bill?”

“They’re reluctant about specific reference to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. His argument is that including it could throw a challenge into federal court.”

“A challenge could throw it into federal court even without that reference.”

“I said that but got nowhere,” Taveras replied. “Martineau also insists that — as in past redistricting — all the commission appointments be by legislative leaders. He doesn’t want criteria for public members.”

“So all they’re offering is to put you on the commission?”

“Martineau said they would actually hold more public hearings than the fourteen we called for.” Taveras hesitated. “I also talked with Bill Irons, who said he wants me on the commission. He told me people will be happily surprised with the way they do this.”

“Excuse my skepticism,” I said. “Irons always says stuff like that. What else did he say?”

“Only that his bill will be the vehicle. And that it will go from the Senate to the House.”

“Angel, there’s an advantage to having you on this commission, even if you’re only one. But I think they’re trying to peel you away from the coalition.”

“I agree,” he said. “But I’m staying with the coalition, and I hope these calls show that they’re taking us seriously.”

The Providence Journal’s political columnist M. Charles Bakst wrote in May that Taveras had landed a seat on the redistricting commission. His profile opened: “It’s a good time to be Angel Taveras.” Bakst speculated about future races, such as mayor of Providence or lieutenant governor. Taveras replied modestly that he was young and learning. “I have an opportunity to help people. I’m developing as a lawyer. I’m developing in politics.”

Taveras told Bakst about a moment of truth in the parking garage below his law firm. A driver had rolled in and asked if he worked there. When Taveras said yes, the driver started to get out, assuming he was a parking attendant.

“No, no,” the young lawyer laughed. “I work upstairs.”

Instead of grumbling about being stereotyped, Taveras told Bakst: “It keeps you humble.”

The Senate Judiciary Committee finally took up redistricting legislation on June 5, 2001. From his seat at the center of the top row, Chair Joseph A. Montalbano explained and defended Irons’ bill, which he had co-sponsored. He described lawsuits over the 1982 Senate plan that had cost the state $1.6 million, and contrasted that with the 1991–92 round of redistricting when he served on the panel: “We traveled across the state, and the end product was not challenged. Senator Irons’ bill sets forth standards that we considered important ten years ago.”

Next, Lenihan presented his redistricting bill. “At the time I introduced this legislation on behalf of the Fair Redistricting Coalition,” he began, “there was no other bill. Subsequently, Majority Leader Irons also filed a bill. If elements of my bill could be incorporated in his, I would be happy.”

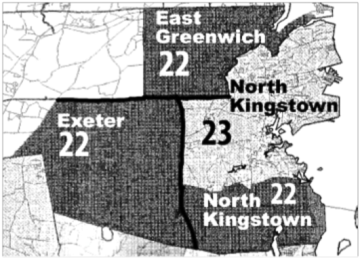

Lenihan looked up over half-frame glasses. “Nine years ago, my experience was horrific. My district slithered southward and wrapped around the district of another senator who was in better standing with the leadership at that time.”

Protests from Lenihan’s constituents and the reform community were fruitless, and the gerrymandered Senate District 22 became law. Since then, Lenihan had tried to keep up with town councils in East Greenwich, Exeter, and North Kingstown.

Ironically, the Bevilacqua stalwart who should have benefitted from his compact district in North Kingstown had lost to a Republican in 1992.

Angel Taveras led an array of witnesses for the Fair Redistricting Coalition. “This time is historic,” he announced. “What we do, people will remember. The public needs to feel confidence in this process. Everyone needs to see how the maps are drawn. We don’t want this to end up in litigation.”

He outlined the coalition’s aims. “One of the standards in this legislation needs to keep communities together. If you follow municipal boundaries wherever possible, most senators will have to deal with only one city council. When you go into multiple cities and towns, that makes it harder for those reps and senators. We think it’s hard to justify two senators crossing the same border and covering parts of the same two towns.

“We also need to take race into consideration,” Taveras continued. “We’ve proposed that Senator Irons’s bill, which we assume will finally pass, be amended to include reference to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. We believe that law is crucial, and if you require the commission to comply, you will almost surely avoid the kind of legal challenge that overturned the Senate’s 1982 plan. We think that’s just practical.”

Joe Fernandez, the lawyer who drafted our bill, explained its details. He said that any state redistricting that violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965 could be overturned. “So,” he suggested, “why not incorporate those requirements in the text of the redistricting law you pass for Rhode Island?”

A dozen witnesses — all representing groups in the Fair Redistricting Coalition — testified to the need for stronger anti-gerrymandering standards, as in Lenihan’s legislation.

Nellie M. Gorbea, the head of the Rhode Island Latino Political Action Committee (RILPAC), urged the Judiciary Committee to take elements from both bills. She rejected the notion that downsizing necessarily hurt minorities: “What matters is how you structure redistricting. If you establish clear standards, you’ll have room to say, ‘Those were the rules of the game, and we followed them.’” Without threatening in words or tone, she eyed each member of the committee.

“Finally,” she said, “I think that members of the General Assembly have a conflict of interest on this issue. It would be a positive step if you would put this process in the hands of people who don’t have a vested interest in the outcome.”

Predictably, members of the Judiciary Committee praised Irons’s legislation, rejected all amendments, and recommended passage to the full Senate. No one from outside the General Assembly spoke in support of Irons’s bill.

The Irons bill became law during the rush toward adjournment in early July. It specified that the speaker and Senate majority leader each appoint six commissioners, half of them lawmakers and half public members; the minority leaders in the House and Senate would each name two legislators. A 12 to 4 majority of Democrats ensured no surprises.

The Fair Redistricting Coalition offered House and Senate leaders a diverse list of community leaders who would be willing to serve as public members of the sixteen-member Redistricting Commission. All were intelligent, pragmatic, and rooted in their communities. We still expected that Angel Taveras and at least one other community advocate would be appointed.

The lists announced by legislative leaders felt like a backhand slap. Although House leaders appointed two people of color — Rep. Joe Almeida and Luisa Murillo — no one from the coalition’s list was named, and Majority Leader Gerry Martineau reneged on his public promise to appoint Taveras.

When Providence Journal reporter Kathy Gregg phoned for comment, I asked why House leaders had changed their mind. “What would be so dangerous about having Angel Taveras on the commission that they would risk publicly breaking their word?”

Taveras was characteristically diplomatic. “We have a lot of talented people in the state,” he told Gregg. “It is a tremendously difficult job, and I wish them the best.”

At the end of July, Irons appointed three powerful senators and a trio of public members that included two Latinas: housing developer Alma Felix Green and banker Yahaira Placencia.

Joe Fowlkes objected that Irons had failed to appoint even one African-American. “The group that has bled more, cried more and tried to ensure voting rights for everybody is a group that should be at the table,” he told reporters. “To say the least, I was not only disappointed but felt insulted.”

Irons replied that he thought Yahaira Placencia was black because of her “non-Caucasian” skin color and the fact that a black constituent had recommended her.

Republicans, with four seats on the sixteen-member panel, might protest partisan abuses but lacked the votes to change any outcomes. The five women and four people of color gave an impression of diversity, but they had little experience with redistricting, and seasoned legislative loyalists would surround them on the panel. Would legislative leaders try to entice them with legislative grants for nonprofits several ran? Would they risk retaliation by challenging gerrymanders? Without strong standards or independent commissioners was the game rigged?

The first public hearing was posted for September 11, 2001.

The shock of hijacked jetliners crashing into the Twin Towers, Pentagon, and a Pennsylvania field overwhelmed all else. While Rhode Islanders watched nonstop live coverage, the Redistricting Commission postponed.

The second hearing went ahead on September 13 at South Kingstown High School, but the shadow of 9/11 made it seem surreal. In a nearly empty auditorium, spectators clumped together among hundreds of vacant seats.

Commissioners appeared quietly from the wings and took seats behind individual microphones on white-draped tables. Chairperson Rep. Denise C. Aiken welcomed the audience and television viewers. She introduced Vice Chairperson Sen. Joseph A. Montalbano and her fellow commissioners. They would begin with six information-gathering sessions around the state; then, during five public workshops at the State House, they would work on the plans. Finally, they would travel around the state again to solicit feedback.

You’re going to like our new software,” Kimball W. Brace told me on my first visit to the mapping room at the State House. The president and CEO of Election Data Services, was back. He still wore aviator glasses, but gray had lightened his hair and beard since his Virginia-based redistricting firm remapped the General Assembly in 1991–92. “This software’s more powerful and more user friendly than what we had ten years ago,” he said as if we were old friends.

A dozen jet-black PCs with flat-screen monitors stood on tables along the walls behind him. “Each of these can create alternative statewide maps quickly and precisely,” Brace said. “You get access to all of our data and maps. You can schedule appointments, and my staff will help you learn the software.”

I asked if he would share the software and data so neighborhood groups could create maps and bring them to the public hearings.

“Sorry,” he smiled. “Software’s proprietary. But if you’re suspicious of anyone looking at your files, bring a zip-drive to save your maps and data. Better than that I can’t do.”

As news media reported on the commission’s hearings around the state, attendance grew. Brace projected vividly colored maps on a huge screen and handed out packets that contained three separate sets of maps: Senate and House versions were separately labeled Plans A, B, and C, for the three plans being considered. With the maps came population data tables for hundreds of possible districts. Brace told audiences that they knew their neighborhoods better than his technicians or members of the redistricting commission. “Compare these various plans,” he suggested, “and come to the workshop sessions ready to make specific recommendations.”

The alternate maps sparked questions of geography, populations, neighborhoods, and political power. The process looked and felt transparent.

Members of the Fair Redistricting Coalition attended all the hearings and provided testimony in their home counties. Angel Taveras and Kevin McAllister had battled a year earlier in the Democratic primary for the 2nd District Congressional seat. Now they pushed the coalition’s principles with a single voice: follow municipal boundaries wherever possible; never crack a community into multiple Senate or House districts if it can be kept whole; keep districts compact and contiguous; pay special attention to representation of ethnic minority communities, particularly groups that have suffered historic discrimination; and avoid creating “voting pockets” of fewer than 200 voters, which are costly and confusing.

After the audience left one hearing, I stood virtually alone with Sen. Joe Montalbano in a vast auditorium. I reminded him that the population of Providence warranted 6.29 Senate seats, and minorities now constituted sixty-five percent of the capital city. I argued that those numbers obliged the commission to create at least two senate districts where African-Americans and Latinos could choose senators who would represent them authentically. I told him resentment was brewing in the black community as Dominicans filled Broad Street with new businesses, and I warned against Senate maps that might force an ethnic showdown. If new districts were to pit the state’s only black senator against a Latino — especially if those maps enabled white incumbents to keep four or five other Senate seats in Providence — ethnic tensions might boil over.

“I hear you, Phil,” Montalbano said in a soothing voice. “Watch and see what we produce.”

My cautious hopes for reasonable redistricting crashed on November 8. During a State House hearing, Kim Brace distributed two new pairs of alternative plans — Senate plans D and E, and House plans D and E. As I sat in the audience comparing maps, suspicious shapes emerged. Blatant gerrymanders appeared like boulders in a stream, forcing other districts to bend around them.

Both Senate plans protected the turf of Federal Hill Sen. Frank T. Caprio, an Irons ally who now chaired the Senate Finance Committee. Caprio’s district maps reminded me of a castle with sturdy battlements. Both versions seized predominantly black blocks that were part of Sen. Charles Walton’s district. Both alternatives would force Walton into the heavily Hispanic neighborhood where Leon Tejada had crushed Marsha Carpenter, an African-American, only a year before. If either plan were enacted into law, the only African-American ever to serve in the Rhode Island Senate would lose.

In the East Bay, both Senate plans created a district that straddled the wide Sakonnet River, joining bucolic Little Compton and parts of southern Tiverton on the mainland with densely populated Middletown and Newport on Aquidneck Island. In either configuration, Middletown’s popular Republican incumbent June N. Gibbs would trounce Tiverton Democrat William Enos, a stalwart of former Majority Leader Paul Kelly. But the two communities had little in common, and serving towns on opposite shores of the Sakonnet River made no sense. A one-way trip from Gibb’s home in Middletown to Town Hall in Little Compton would take her north on Aquidneck Island, across a bridge to the mainland, and then south to Little Compton — four miles by helicopter but more than twenty by car. This bizarre configuration would force her to drive through two other Senate districts to cover her own. Gibbs blasted the maps as “pure gerrymander” and told reporter Edward Fitzpatrick about her family tree, which traced directly to Elbridge Gerry.

During a brief chance for public testimony, several of us deplored what looked like blatant gerrymandering in both proposed Senate plans. On my way out, I reached to shake Bill Irons’s hand, but he pulled away. “You talk like that,” he roared, “and then want to shake my hand? You are utterly disingenuous! I will never shake your hand again in this building.”

A few days later, the Providence Journal published my critique of the new Senate maps. I called the Federal Hill district that would protect Irons’s ally “Caprio’s Castle,” and the East Bay plan that would oust Sen. William Enos “the Sakonnet Swim.” I noted that earlier Senate maps had offered more neighborhood-friendly districts but those had now been “swept into the trash.”

I wrote that both Senate plans contained variants of a Coventry district that looked like a land-locked riverboat. It lay stranded across the backyards of four communities — its waterline stretched along the boundary between Coventry and West Greenwich, its smokestack rose toward Cranston, and its prow plunged through East Greenwich and West Warwick into Warwick. I dubbed it “the Coventry Steamboat.” What could possibly justify it?

The map made no sense until I checked on representatives who might run for the Senate seat. An aggressive and ambitious Warwick Republican, Rep. Joseph A. Trillo, lived in the prow, at 19 Gilbert Stuart Drive in Warwick. The “steamboat” presented Trillo with unpalatable choices: run in a Coventry Senate district he could never win, move elsewhere in Warwick, or stay put in the House of Representatives.

House leaders also produced cartoon-like maps. I called one the “West Warwick Warbler.” It sat squarely at the southern end of West Warwick with its neck stretched east into Warwick, as if it were pecking at Interstate 95. Its tail feathers spread westward into Coventry, where it seemed to be laying an egg — Tiogue Lake. The new district would fracture representation for West Warwick, one of Rhode Island’s poorest cities. Two of the three House districts in the city would reach needlessly both east into Warwick and west into Coventry, mocking the principle of keeping districts within municipalities wherever possible.

As Irons had done in the Senate, Harwood thrust his antagonists into districts they would find hard to win. Rep. Charlene M. Lima, an early separation of powers sponsor, who often challenged House leaders, would have to battle two incumbent female Democrats: Beatrice A. Lanzi and Mary Cerra. Rep. Elizabeth M. “Betsy” Dennigan, who also pushed separation of powers, found her East Providence district flipped north into Pawtucket with little more than her own block on familiar turf. The bulk of the proposed new district had belonged for twenty years to Mabel Anderson, who was retiring but had bestowed her political mantle on her son.

The Providence Journal analyzed the redistricting maps and found that sixty-seven percent of women in the House would have to campaign against other incumbents, while only forty-one percent of their male colleagues would. On the Senate side, seven of the ten female senators were pitted against other incumbents, but fewer than half the men were.

Sen. Rhoda E. Perry declared the Senate still “a boys’ club.” Like Lima, she had sponsored separation of powers bills since 1995 and had remained loyal to ousted Majority Leader Paul Kelly; now she found herself among the women forced to square off against other incumbents. “I think it will reduce the number of effective women legislators,” Perry told reporters, “and we are a minority group within the General Assembly.”

The Senate plans also overwhelmed people of color. White incumbents held three Senate districts with large minority populations, while the sole African-American senator would probably lose to a Latino. I warned publicly that if that were to happen, “Senator Irons will rue this day, and there will be lawsuits.”

Irons fired back that I was being “disingenuous” and blamed me for pushing to downsize the legislature. He declared that I had created the dilemma being visited upon minorities and accused me of jeopardizing their future.

As the Redistricting Commission finished its final public hearings, the real drama played out in private meetings as Irons and Montalbano summoned senators individually to Irons’s office and unrolled their final maps. With no hope of change, the Fair Redistricting Coalition notified the press that it would make an announcement half an hour before the commission’s next-to-last public hearing.

Dozens of clergy and community leaders arrived at the hearing room but found its door closed. Bishop Robert E. Farrow, an imposing presence and long-time pastor of the Holy Cross Church of God in Christ on Broad Street, pushed it open and looked inside. There, at the long witness table, Irons and Montalbano sat with Charles Walton. Maps lay between them as they humiliated Walton and prevented others from entering the room.

“Out here in the hall,” Farrow declared in a booming voice and slammed the door. “We shall not be put to shame!” His King-like cadences filled the hallway. “We shall not be defeated! All of us together, we shall not be moved! Let us join hands and pray!” Farrow began calling down fire on the Senate’s gerrymandering. Shouts of “Amen!” drove his message through the thick oak door.

From the hallway protesters raised their voices. Dr. Pablo Rodriguez, a respected obstetrician and president of the Rhode Island Latino Political Action Committee, blasted the Senate maps. “We will not allow African-Americans to be pitted against Latinos in a struggle for political crumbs,” he declared. “We are here today together, we will protest together, and we will go to court together, if that is the path we are forced into.”

Former Rep. Harold Metts, now head of the Minority Reapportionment Committee, bellowed that the issue was racial packing: “One super majority-minority district of eighty-one per cent that pits blacks against Hispanics is not the answer. Two districts could easily be created to protect the interests of both communities, but they have not done that.”

Irons later spoke with reporters. He insisted that the commission had “done its best to empower the minority community.” He accused his critics of simply trying to elect both Walton and Pichardo. “That’s not about empowering minorities for the future,” he insisted. “That’s about anointing a few minority candidates.”

Irons also criticized Paul Kelly. “We have no split, no faction,” Irons insisted. “Right now there is a great degree of collegiality, and we went for eight years with tremendous discord and rancor under Kelly.”

For the first time, Kelly fired back at the gerrymandering that would eliminate him and his supporters. The proposed Senate map would leave Kelly with less than nine percent of his old Smithfield and North Smithfield district. He found himself in a district that looked like water sloshing over the top of an aquarium that was Glocester and Burrillville — with his house in the splash. To continue in the Senate, Kelly would have to run against his ally, Sen. Paul W. Fogarty, on Fogarty’s home turf, a move he would never attempt.

“It seems to me a blatant abuse of redistricting,” Kelly told reporter Edward Fitzpatrick, “to come from Glocester through Burrillville to my house on Victory Highway in North Smithfield. I wonder what their position would be if I moved over two streets. Would they reconfigure the maps again?”

Neighborhoods and entire towns were being dismembered so that Irons and his faction could oust Kelly loyalists. Irons seemed to be multiplying the very mistake Rocco Quattrocchi had made twenty years earlier, and the consequences could again be ugly.

On December 11, all sixteen members of the Redistricting Commission approved the Senate leadership’s plan. The closest thing to a protest came from Rep. Joe Almeida, who chaired the Black Caucus of State Legislators. He asked to vote separately on the House and Senate plans. He said he could not vote against the House maps, which were fair for his district, but neither could he approve the Senate maps, which were not. In an extraordinary ruling, Chair Denise Aiken rejected Almeida’s request to vote on the legislation by sections. Almeida expressed his disappointment: “I know that the new census figures show more than half of Providence’s population is now nonwhite. We are not going to wait ten years or five years or even three years.”

“It didn’t have to be this way,” declared Pablo Rodriguez, head of the Rhode Island Latino PAC. “We could have had two districts where minorities could have been elected.” Rodriguez blamed the three Latinas — Alma Felix Green, Yahaira Placencia, and Luisa Murillo — who sat virtually silent on the commission throughout the process. All three voted for the plan; none raised the challenges that an array of community groups sought. Had the women been naive participants in this performance? Would their nonprofits receive legislative grants or other favors?

One January afternoon at the State House I stepped into a men’s room. From the back, Bill Irons’s familiar shoulders and neatly trimmed gray hair were unmistakable at the next urinal. For an instant, we stood shoulder to shoulder in silence.

“How are you?” I asked.

“Fine,” he said, trapped. “How are you?”

“Fine.”

“Good.” He stepped away to the marble sinks.

We dried our hands in awkward silence, both aware of his pledge never to shake my hand again in the State House. Our eyes met for the first time. I offered my hand.

He shook it. “Take care,” he said and left.

Only days before final votes on redistricting, Sen. Charles Walton met with the Fair Redistricting Coalition. “I’ve talked with a lawyer in Washington,” he said. “She thinks we’ve got a strong case that this is racial gerrymandering. She suggests that we file in U.S. District Court. We’ve laid a good foundation. We pushed to incorporate the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and they refused. That’s unmistakable legislative history.”

Walton said Irons knew he was establishing a record but took that as a sign of mistrust. “At one point,” Walton added, “he stormed by me and said: ‘I will never forget this.’”

“He thinks he’s righteous on race,” said Kevin McAllister. “He’s protecting incumbents who are loyal to him, and the U.S. Supreme Court has said they can consider incumbency. They’ll argue that they carved your district up because they had no choice.”

Walton nodded. “My answer is that you can’t come in legally and destroy the largest cohesive minority district in the state. They carved the only predominantly black district into three pieces.”

McAllister agreed that Walton’s point was strong. The question remained whether protecting minority communities of interest would trump protecting incumbents.

Walton focused his indignation. “I would argue that — downsizing aside — Juan Pichardo ran hard against Bob Kells in District 10. We got so close that it was a photo finish. Now they’ve split that district, too, and they force me to run against Pichardo on his turf. For two decades we’ve had steadily increasing minorities on the South Side, and every time we get close, they redraw lines to favor Caucasian incumbents, in this case Caprio and Igliozzi.”

Irons’s redistricting bill landed on the Senate calendar for February 7, 2002. Its street-by-street description of boundaries filled ninety-two pages.

Only a handful of senators dared to attack the Irons-Montalbano maps. None expected to win, but their strategy was to force public votes on two sets of amendments. The first set aimed to make the East Bay Senate districts “compact and contiguous” under the requirements of the Rhode Island Constitution. The second set would establish Providence districts that would pass muster under the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Newport Sen. Clement Cicilline offered an amendment that would restore an early alternative plan in place of what I dubbed “the Sakonnet Swim.” In one stroke, Cicilline’s motion harmonized the entire map of East Bay Senate districts so that no senator would need to cross through any other senators’ districts to reach distant constituents. The amendment went down to defeat, 39–8.

Then Mary Parella of Bristol offered a similar amendment. The Senate leadership’s plan fractured her historic town into three pieces, each joined with parts of neighboring towns. With Parella’s replacement plan, as with Cicilline’s, the scrambled districts could become whole and compact, despite the area’s picturesque peninsulas and islands.

Sen. Bill Enos — the majority whip under Kelly — spoke for Parella’s amendment and blamed Senate leaders for fracturing the entire East Bay to knock him out. “Gerrymandering is bad,” he roared at Irons, “but ‘Billy-mandering’ makes Gerry’s plan look good.” I had never heard Enos attack in such a personal way. “Hear me, Senator Irons. You’re a proud man. I know you are, Billy. Don’t leave your legacy this way — that you decimated Newport County.”

Murmurs spread as Irons sought recognition from the lieutenant governor. “I wish Senator Enos would stop haranguing other senators,” Irons growled. “It is totally out of the decorum of this chamber.”

When Parella’s amendment failed, 34–11, Enos presented his own amendment and reargued his case for keeping Tiverton and Little Compton — both on the Massachusetts side of the Sakonnet River — as a single district. His amendment went down in a blaze of red lights on the electronic tote boards: 36–9.

Finally, Charles Walton rose to present the first of four amendments. He asked his colleagues to take parts of Upper South Providence away from Frank Caprio’s district and create two majority-minority districts on the South Side. Even in the supercharged heat, he spoke with the quiet modesty of his North Carolina childhood: “After all this time, to have only one minority district — shame on us for not having the vision to be more inclusive.”

Montalbano defended the commission’s plan against Walton’s amendments but seemed to be only going through the motions. “To suggest that we either ignored or disrespected minority voting rights,” he insisted, “is disingenuous, at best.” He claimed Providence would have five majority-minority districts in spite of the downsizing. “In two, four, ten years from now,” he insisted, “if the population trends continue, these districts will be very good targets for minority voting strength.”

As if he had been waiting for that, Walton reached for a book. “I’ve been here twenty years, ever since a civil rights lawsuit proved racial gerrymandering in 1982. I keep hearing the same refrain: ‘Wait a little longer. Your time will come.’ ” He raised Dr. Martin Luther King’s book Why We Can’t Wait so all could see its title. “This is a real chance to enfranchise the community. How long do we have to wait for the representation we deserve in Rhode Island?”

Predictably, each of Walton’s four maps fell under columns of mostly red lights. In a few months he would lose in the Democratic primary to his friend, Juan Pichardo. The stage was set for lawsuits.

Read the Rest of the Chapter Here

Related Slideshow: Rhode Island’s History of Political Corruption

Related Articles

- Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 24

- Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 23

- Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 25

- Secrets and Scandals: Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 26

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 27

- Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 22

- Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 21

- Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 18

- Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 19

- Secrets and Scandals - Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 20

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 28

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 29

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 37

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 36

- Newport Manners & Etiquette: Secrets for A Successful Thanksgiving

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 38

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 39

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 35

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 34

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 30

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 31

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 32

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 33

- Secrets and Scandals: Reforming Rhode Island 1986-2006, Chapter 40