Rhode Island Government Failure: RISDIC - Collapse of Credit Unions in 1991

Monday, April 01, 2024

Editor's Note: We take a look at how the Rhode Island government has failed in the past to protect Rhode Islanders. The ongoing investigation into the failure of the Washington Bridge may be the newest breakdown and failure of providing basic protections and services. We take a look back for similarities and lessons.

H. Phillip West, Jr. wrote the book SECRETS & SCANDALS: Reforming Rhode Island. GoLocal has previously published the entire book -- we reprint this chapter. Part One: DiPrete, RISDIC Chapter Five: Collapse of Credit (1991)

Bruce Sundlun’s inauguration and a new year fell together on January 1, 1991, one of the worst days in Rhode Island’s history. I leaned into a stiff wind, crossing brittle frozen grass toward the inauguration on the south plaza of the State House. With temperatures well below freezing, the crowd’s glove-muffled applause faded quickly.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTSundlun stood, triumphantly bareheaded, on white marble steps amid flags and dignitaries. At the age of seventy, he had finally toppled the scandal-tainted DiPrete. The campaign had touted Sundlun’s decorations for flying bombers in World War II. When German anti-aircraft fire crippled his B-17, Sundlun and his crew parachuted into enemy territory, where he evaded capture for ninety-five harrowing days and nights. Sundlun, who was Jewish, often told audiences how a network of Catholic priests protected him and helped him escape to neutral Switzerland.

The growling rumble of heavy propeller-driven planes sounded suddenly as a formation of four-engine olive drab military aircraft rose over College Hill and swooped toward the inauguration. They roared in low, their acrid diesel exhaust punctuated by artillery that thudded nearby and echoed sharply from the marble State House. Puffs of white smoke blasted upward and then dispersed in the wind.

In his inaugural address, Sundlun spoke of two storms that the people of Rhode Island must fly through with his new administration: a banking crisis that few understood and an unprecedented budget crisis. “On the approach,” his voice boomed, “The storm cloud is ominous and dark. Once inside, it’s a rough, difficult, tumultuous ride. But once you get to the other side, there is sunlight once again.” He promised to restore the public confidence that DiPrete had shattered. “Nothing can withstand the weight of public cynicism,” he roared. “Without the people’s trust, our task will become an arduous, sullen struggle doomed to failure.”

Afterwards, in the warmth of the State House, word spread that Sundlun would hold a press conference. I squeezed into his formal office, where television lights blazed.

With cameras rolling, Sundlun signed two executive orders. In the first, he pledged high ethical standards of government and established an ethics task force to recommend systemic reforms. The new governor required companies and individuals who received more than $1,000 in state business to report their political contributions over $200. In the second executive order, Sundlun closed forty-five credit unions, seven loan-investment companies, and three banks — the entire ensemble insured by the Rhode Island Share and Deposit Indemnity Corporation (RISDIC). Sundlun saw himself in the mold of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had been inaugurated during a bank crisis in 1933. Roosevelt suspended banking nationwide, but euphemistically called his shutdown a “bank holiday.” Sundlun used the same term for his RISDIC closure. He said some of the insured institutions were healthy and could reopen quickly; others were shaky, but could be put on firmer footing and then reopened. But he said little about the rest — credit unions that were insolvent and must be liquidated.

News of the shutdown reverberated like a bomb blast. a third of all Rhode Islanders had their checking, savings, and mortgages in RISDIC-insured credit unions. The collapse plunged Rhode Island into its worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

For years, the insurer had run reassuring television commercials featuring muscular hands that chiseled a slab of rock. Dust and stone chips flew, revealing the logo: an eagle holding a clutch of arrows above the letters RISDIC. an authoritative voice assured viewers that RISDIC’s security was “carved in stone.” Within hours, RISDIC’s commercials became the butt of bitter jokes. Three years earlier, as Anne and I prepared for our move to Rhode Island, our realtor took us to the east Providence credit Union for a mortgage. Anne asked him why the decal on the door said RISDIC and not FDIC.

“It’s just how we do it in Rhode Island.” At the time, I had no job, and Anne’s salary might not qualify us for a mortgage, so we went along with him. Now our accounts were frozen, too.

In the aftermath of RISDIC’s collapse, furious depositors swarmed the State House. Thousands who had never before set foot inside their splendid capitol came tramping past silent Civil War cannons and faded battle flags, up the broad marble stairs. They waved protest signs and screamed their rage: “We want our money! We want our money!”

Each barrage of shouts echoed from the frescoed dome, two hundred feet above. Mobs of depositors surged past offices and committee rooms. Some kicked thick oak doors, making them bend inward and snap back against their jambs like gunshots. Volleys moved as battles shifted. Outside the House chamber, a huge ship’s bell clanged incessantly until custodians removed its striker. Protesters spewed blame indiscriminately against any public officials they encountered and against government itself.

I found myself at the edge of one depositors’ rally when word spread that two women standing nearby were state representatives. The mob pressed in around them.

Rep. Sandra J. Campbell, a newly elected Republican from rural Foster, stood her ground. “Listen,” she shouted, “I was just elected. I had no part in making this mess.” She made eye contact with a burly man in the front row and held his gaze. “I’m as mad about this as you are. I’m here to make it right.” Her sheer courage kept them at bay and the surge eased. Jack Kayrouz, the leader of the newly organized citizens for depositors’ rights raised a chant through his bullhorn. Protesters shifted their attention back to Kayrouz.

Stitt Report

Only days after this disaster hit a confidential report surfaced. Written more than five years earlier, it predicted RISDIC’s collapse with uncanny precision. Arlene Violet, a former Sister of Mercy, had won the election as the state’s top prosecutor in 1984, the first woman in the United States to be elected state attorney general. In that role, she prosecuted the 1985 scandal involving top officials at Rhode Island’s housing agency, RIHMFC. When she noticed irregularities in a routine report from RISDIC to the Department of Business Regulation, Violet appointed retired New York banking lawyer Robert Stitt as a $1-per-year assistant attorney general and set him loose to probe the insurer’s practices. to back him up, she assigned a former banker, Charles O. Black.

Stitt delivered his report to Violet on December 13, 1985, five years to the month before his nightmare scenario played out. He warned that many credit unions and loan companies were engaging in “all sorts of dangerous, indeed reckless management practices.” He detailed seven hazards that ranged from “large, risky, improperly documented loans” that had produced “high delinquencies and substantial losses” to “unorthodox accounting/management practices” that attempted “to give an appearance of solvency to their balance sheets.” One section of Stitt’s report described “Unduly concentrated loans to Officers, directors and other ‘Insiders.’” The next described “Microscopic reserves.” audits of RISDIC had been irregular and superficial; worse still, officers at several credit unions had intimidated state bank examiners. One employee at the Greater Providence Deposit Corporation was suspected of letting air out of bank examiners’ tires, and also brandished an M-16 rifle in the room where auditors were working. Three institutions — including the East Providence Credit Union where Anne and I had gotten our mortgage and opened our accounts — were in serious financial condition, so that a run on any of the three “would exhaust RISDIC’s available resources” and would probably bring down the entire system.

“The Stitt Report,” as it was quickly called, noted that state-chartered credit union insurers had failed recently in Nebraska, Ohio, and Maryland. RISDIC “would perform no better.” Stitt concluded: “to allow $1 billion in deposits of some 300,000 persons to be held by financial institutions with no federal insurance is archaic and dangerous.”

Atty. Gen. Violet had understood that Stitt’s dire warning could trigger a run on credit unions and bring the system crashing down. She delivered a confidential copy to DiPrete, who ordered a follow-up analysis by one of his lawyers. Normand G. Benoit validated Stitt’s description of a disaster waiting to happen: RISDIC-insured institutions would fail as their counterparts had in Maryland and Ohio.

Violet also gave copies to Rhode Island’s Board of Bank Incorporation, a regulatory body where she served with the general treasurer, director of business regulation, one state representative, and one state senator. All received both Stitt’s original report and Benoit’s confirmation, yet the board took no action. As for DiPrete, he fired off a three-sentence memo to his director of administration, Fred Lippitt, acknowledging the “extremely serious potential” of these revelations, but apparently did nothing further.

Stitt’s report had remained secret for five years, and most Rhode Islanders had never heard of him before his dire warning landed on front pages and television news on January 4, 1991, shortly after Sundlun’s inauguration. The Providence Journal printed what became known as “the Stitt Report” in its entirety. Stitt’s unheeded warning hit me with a jolt of adrenalin. How could officials have known this for five years and ignored it? Why were ordinary people left vulnerable and unprotected?

On the Providence Journal’s editorial page, Brian Dickinson wrote that he had called a national rating service in Wisconsin. “We’ve been flagging RISDIC for two years,” an expert told him. Several Rhode Island credit unions were ominously overextended. Dickinson connected other dots and backtracked to a meeting of the House Finance Committee in 1986, which had rebuffed Violet and dodged the question of RISDIC’s peril. His column rang a bell for me. Hadn’t there been a case before the old Conflict of Interest Commission? Deep in files transferred to the Ethics Commission, I found proof that Arlene Violet and Bob Stitt were not the only ones who agonized over the risks that RISDIC posed.

J. Robert Bergeron had been president of the Woodlawn Credit Union. In that role, he sat on the RISDIC board. He read what he believed were improper audits and raised hard questions, but other officers scorned his warnings. Bergeron gave up on RISDIC and persuaded the Woodlawn board to switch its insurance to the National Credit Union Administration. With his credit protected Bergeron might have dropped the issue, but instead, he reached out to Rep. Francis A. Gaschen, a Democrat from Cumberland. He asked Gaschen whether legislation could require all Rhode Island credit unions to do what Woodlawn had done: obtain federal credit union insurance. He believed some RISDIC institutions would qualify for federal insurance, while others that were overextended or weakened by risky loans might have to close.

Gaschen was not a banker and knew nothing about the Attorney General’s investigation, but he had heard worrying stories from RISDIC depositors in his district. He drafted legislation that would require all Rhode Island credit unions to get federal deposit insurance, a move he knew would end RISDIC’s role as insurer. a copy of Gaschen’s bill went to Sen. John R. D’Amico, a Cranston Republican, who introduced an identical version in the Senate.

It was clear that RISDIC’s allies in the General Assembly had a lot to lose if Gaschen’s bill became law. Rep. Robert V. Bianchini of Cranston was president of the Rhode Island Credit Union League, RISDIC’s trade association; thus, his livelihood depended on the in-state self-insurance system. Because Bianchini also served as vice chair of the powerful House Finance committee, under the conflict of Interest law, then in effect, he should have disclosed his conflict of interest and recused himself from further action on Gaschen’s bill.

Instead, three days before the hearing on the Gaschen bill, Bianchini hosted a dinner for his fellow committee members at the posh Aurora Club on Federal Hill. He and RISDIC President Peter A. Nevola pitched their case against federal insurance. Bianchini gambled the entire RISDIC system on a bet that its most reckless and overextended institutions would not fail.

Violet spoke to leaders of the committee and offered to present Stitt’s report in a confidential executive session, subject only to the condition that Bianchini not be present. They refused.

Despite his blatant conflict of interest, Bianchini had presided over part of the committee’s five-hour hearing on May 12, 1986. Prepped with talking points from their Aurora Club dinner, RISDIC’s backers hung tough. They cross-examined Gaschen as if he were a hostile witness and swatted away the warnings from within the credit union movement. During that tumultuous hearing, Robert Stitt met Frank Gaschen for the first time and handed him a copy of his report, which Violet kept confidential for fear of triggering a run on credit unions.

RISDIC’s obstruction crushed the federal deposit insurance bills in both the House and Senate. As I tried to piece these fragments together, the wrongs of 1986 came alive. The governor had been so busy running his pay-to-play scheme and amassing campaign contributions that he ignored clear warnings of the coming collapse. To protect Bianchini, the Finance Committee ganged up on Gaschen and trashed his bill. Just as Bob Stitt had feared, RISDIC’s powerful allies at the State House won. With the help of generous campaign contributions, well-connected lobbyists, and inside players like Bianchini, RISDIC stayed in business. Gov. DiPrete and the General Assembly failed to protect the public.

But Robert Bergeron refused to let go. He spelled out the details of Bianchini’s behavior in a complaint to the Conflict of Interest Commission, and his allegations led to a full hearing behind closed doors. Five votes were required to convict, but only four voted that Bianchini had “knowingly and willfully violated” the law. One of the votes to exonerate him was cast by Michael A. Morry, the President of the Warwick Municipal Employees Credit Union, which relied on RISDIC insurance. Thus it seemed painfully clear that Morry had his own blatant conflict of interest on the very panel that was supposed to protect the public. Only a few days after Morry voted to clear Bianchini, DiPrete signed the law that put the Conflict of Interest Commission out of business and created the Rhode Island Ethics Commission. On the recommendation of House leaders, DiPrete named Michael Morry to the new panel.

No amount of hindsight could undo that history: Bianchini was protected by the constitution from being charged a second time for the same conflict of interest. Yet with our complaint pending against DiPrete and more complaints likely against key RISDIC players, it seemed absurd that Morry should be in a position to acquit his cronies in the future. Common Cause demanded that Morry resign, but he refused, and his fellow commissioners did nothing, while the media paid little attention. Our concerns about one credit union executive vanished like a paper airplane swept up in a hurricane.

Within days of RISDIC’s collapse, Bianchini became the villain. angry depositors chanted his name as a curse. Protesters taunted him at the State House. On January 7, the beleaguered official resigned from his two powerful posts in the House leadership: deputy house majority whip and vice chair of the House Finance committee. In a letter to House Speaker Joseph DeAngelis, he acknowledged his lead role in killing Gaschen’s 1986 legislation. “I am saying openly and honestly today that I was mistaken.”

A few days later, I stepped out of a rotunda full of protesting depositors and into the relative quiet of a gallery that overlooked the House chamber. a steep stairway gave access to benches on either side. In the red-carpeted aisles below, representatives were chatting or collecting signatures on bills while they waited for the afternoon session to start. I took my usual seat in the gallery’s front row and opened a folder of bills.

“Which one’s Bianchini?” a man in a pale polyester suit had entered after me. His hair was white and neatly trimmed. I glanced at representatives on the floor. Bianchini was nowhere in sight, and I told him that.

“I’ve got a gun,” he said softly, his right hand deep in a pocket. “I’m going to kill that son-of-a-bitch.”

“That wouldn’t solve anything,” I said, trying to look calm despite a rush of adrenalin. Even with rage smoldering and flaring up everywhere across Rhode Island, the State House still had no metal detectors. Three entrances stood wide open and unguarded, with no checks of bags or briefcases. Anyone could walk in or out. Chaos reigned in the corridors. The House chamber lay vulnerable below us. No capitol police were in sight.

“Do you see him?” the man demanded. “Bianchini?”

With his neatly trimmed mustache and goatee, Bianchini would have been instantly recognizable. “I don’t see him,” I said truthfully. “let’s go outside and talk about this.”

The man ignored my offer, his eyes searching the throng of people below. I thought of Puerto Rican nationalists firing on Congress from a gallery half a century before and wondered about this grandfatherly man. Would he recognize Bianchini if he entered the chamber? did he really have a pistol? Would he try such a long shot?

The whole thing seemed wildly improbable. I hesitated, moved away from the white-haired man, and tried to fade from his presence. I climbed the gallery’s carpeted stairs and escaped into the rotunda. I searched for a police officer but could not find one. Racing to the Speaker’s office, I told a receptionist and asked her to call police to the gallery. Back in the gallery, I opened the door and looked inside, but the space was empty. The white-haired man had vanished. I bolted back out to the rotunda and scanned the long hallways without seeing him or police. an elevator beeped its arrival at the third floor, and a clutch of angry depositors spilled out. There were no officers among them. I hurried back to the Speaker’s office just as DeAngelis came out with his entourage. I said it was an emergency and pushed through to tell him about the threat. Distracted, he thanked me and strode down the back stairs. His retinue of representatives and staff followed.

At the top of the stairs, I felt foolish. I stepped into the west gallery above the rostrum and looked across at the opposite gallery. a dozen or more protesters occupied the front row. On the House floor below, Bob Bianchini was nowhere in sight.

The public’s hostility to RISDIC grew by the day. A week after the collapse, hundreds of us who had funds frozen in the East Providence Credit Union filled the seats and stood in the aisles of a school auditorium. The credit union’s officers sat on the stage behind a table. Anthony Aragona, the thrift’s president, rose with a microphone in hand but was hooted down.

“My business is going under,” shouted one woman near me. “I want to know how many of you people took money out before they closed the bank.”

Aragona shouted through the public address system that none had withdrawn funds and that his account was frozen along with hers. Meanwhile Sen. John F. Correia, a vice president of the East Providence institution, translated parts of the meeting into Portuguese. Correia tried in vain to convince the audience that he had not known that East Providence, or RISDIC, as a whole, faced grave financial peril. But time would reveal what Correia tried to hide; within days other senators tipped off reporters that Correia had helped bury D’Amico’s 1986 Senate bill requiring Rhode Island credit unions to get federal insurance. He knew that the East Providence Credit Union could not qualify for insurance from the National Credit Union Administration.

Sundlun and Gregorian

As the crisis mounted, Gov. Sundlun asked the president of Brown University, Vartan Gregorian, to form a panel and find out why the RISDIC system for protecting deposits had not worked. In answer to reporters’ questions, he admitted that Gregorian’s panel would have little money and no subpoena powers. The new governor had come into office with a mandate to clean up cronyism, but in the maelstrom, he seemed unable to focus on prosecuting those responsible for this disaster.

Atty. Gen. James O’Neil asked Sundlun for extra funds to hire investigators with expertise in white-collar financial crimes, but the governor refused, growling, “It’s more important to get the money into the hands of the depositors than to find out who may have been at fault.” O’Neil offered instead to find volunteers to run an investigation. Bank examiners and state troopers were already poring through boxes of files from Heritage Loan and Investment. Meanwhile, other lawmakers proposed separate investigations. Senate Majority leader John J. Bevilacqua appointed a committee of seven senators to study the causes of the crisis and suggest new banking laws. House leaders announced that the House Judiciary committee would conduct its own probe. Its chair, Jeffrey J. Teitz, had led the impeachment investigation against Bevilacqua’s late father, the former chief justice, for associating with mobsters.

RISDIC investigations multiplied like school closings in a blizzard. after two weeks it was hard to tell whose tracks might be lost in a snowy crime field trampled by many searchers. What would happen if legislative investigators were to grant immunity to key witnesses? It seemed clear that only an independent special l prosecutor from outside Rhode Island could follow the money, as Archibald Cox had done with Watergate.

The newly elected Sundlun had no responsibility for the credit unions’ collapse, but RISDIC was fast becoming his crisis. Days slipped away, and crucial decisions were skidding out of control. On behalf of Common Cause I wrote him that it was time for an independent prosecutor, which would help to avoid any appearance of a cover-up. The letter encouraged Sundlun to insist that legislative leaders halt their separate investigations, since otherwise key evidence might be lost: “Uncoordinated, compartmentalized investigations will inevitably have the effect of disbursing, losing or destroying information.” Finally, I urged Sundlun to protect all RISDIC-related files from tampering, particularly documents scattered around various credit unions.

On January 11, I hand-delivered the letter to Sundlun’s office and then walked around the building, leaving copies for General assembly leaders. Finally, I dropped off copies for reporters in their cramped basement offices.

a few days later, after an evening hearing of the House Judiciary committee, chairman Jeff Teitz drew me into his office. Teitz towered over me, looking down through thick glasses. “I wanted you to know,” he began, “that I’ve been talking with our leadership in the House and with the governor. We’ve agreed on a single RISDIC investigation, as you requested.” He described to me the commission that he would lead and whose members would be appointed by the governor, attorney general, and legislative leaders. “We will have the power to subpoena documents and witnesses, and I assure you that we will be extremely cautious in granting immunity.”

“I don’t mean to question your judgment,” I said respectfully, “but we asked for an independent prosecutor from outside Rhode Island.”

“I was just getting to that,” Teitz said, not taking offense. “We’ve spoken with a number of people, but I’m leaning toward two respected prosecutors whose names I’m sure you’ll recognize. Both are from out of state, and both have extensive experience with white-collar crime. We’re nearing a final agreement that I think will please you.”

Almost as if it had been planned, his phone rang. He thanked the caller for getting back to him. I rose to excuse myself, but he gestured for me to stay. The call was brief, confirming arrangements for a flight from Washington. Teitz hung up, wrote himself a note, and looked across his desk at me. “You may have guessed who that was, and I trust you to keep this confidential until we finalize the details and make an official announcement. That was John Nields, who was lead prosecutor in the Iran-contra investigation.”

The second outside prosecutor would be Alan I. Baron, who had led the investigation of a federal judge impeached in 1988 by the U.S. House of Representatives, found guilty by the U.S. Senate, and removed from the bench.

A few days later, Atty. Gen. Jim O’Neil called our office to let me know the governor would soon announce a RISDIC probe that would involve two out- of-state special prosecutors and a single investigating commission. “I have one appointment on the panel,” he said, “and I’d be open to any suggestions from Common Cause.”

I suggested Rae Condon. “She’s an excellent lawyer who ran the Conflict of Interest commission for ten years.”

“I haven’t met her,” O’neil said. “Is she related to former chief Justice Francis condon?”

“His daughter,” I said and gave him her phone number.

As weeks passed, several credit unions got insurance from the NCUA. While they reopened, most remained locked tight.

Impatient depositors turned their rage against Sundlun and his staff. No one seemed immune. after one late hearing, I went to ask Sheldon Whitehouse, Sundlun’s young executive counsel, about an ethics bill. The receptionist had left, and I found Whitehouse alone in his office looking shell-shocked, sunk back in his chair.

“Sorry,” he said. “too many hours burning the candle at both ends.”

I could feel his isolation. “Do you think that they can’t tell who’s responsible for the mess and who’s stuck with cleaning it up?”

“I think they know by now who’s who,” the young lawyer said.

“But they’re venting at you?”

“The word’s around that we made it worse by declaring a bank holiday.”

“Did you have a choice?”

“I don’t think we did.” In the dim light, Whitehouse looked utterly bereft. “I

got here this morning at six-thirty and there was already a little old lady waiting at the sub-basement entrance. She looked sweet and grandmotherly, like the muffin lady. She squinted at me as if she recognized me. ‘are you Sheldon Whitehouse?’ she asked.

“‘Yes,’ I told her. ‘Why do you ask?’

“‘You mother-f**ker,’ she hissed at me. ‘I hope you burn in hell and that your children die of cancer.’” Whitehouse shook his head sadly. “It’s like they’ve all flipped out on something. They can’t hear a word about where we are or where we’re going.”

I suggested that he go home and have dinner with his wife and children.

“The kids are probably in bed already,” he said. “We just got a big new TV for christmas, and Molly saw me on it. She thinks I’ve gone somewhere far away. She keeps asking Sandra when I’m coming home.”

“Right now,” I said. “and I’m walking you to your car.”

“And hope the muffin lady’s gone by now?”

“And hope she feels some remorse.”

“Don’t hold your breath waiting.”

We walked out to the parking lot. His was one of the last cars left.

On Valentine’s Day, Rhode Island’s new governor convened a press conference in the ornate State Room to announce the creation of a single RISDIC Investigating Commission. The white-haired governor burst from a doorway to his office and marched to the lectern, with aides in tow. Those who were to serve on the new commission filed in after him and took seats in rows of chairs slanted toward the lectern. Sundlun stood in front of the carved white marble fireplace, under the full-length portrait of George Washington.

Sundlun spoke with gruff authority. “I’m about to sign an executive order that will establish a select panel to probe the risks taken by RISDIC and its member institutions. Our investigation will search out failures of government, particularly insider influence.” The entire crisis, he told us, was caused by “irresponsibility, naked greed, and a casual standard of political ethics.” Then he introduced Jeff Teitz to lead the investigation: “I have complete confidence in his integrity, his intellect, and his independence.”

Sundlun next presented his four appointees: retired Superior Court Judge William M. Mackenzie, District Court Judge Alton W. Wiley, Supreme Court Disciplinary Counsel Mary lisi, and North Kingstown Police chief John J. Leyden. He also introduced four panelists selected by other state leaders: Common Cause Vice President Rae B. Condon, chosen by the attorney general; Rep. Francis A. Gaschen, by the House majority leader; Sen. John F. McBurney, by the Senate majority leader, and Rep. David W. Dumas, by the House and Senate minority leaders.

By naming Gaschen, House leaders seemed to show that they understood how wrong their predecessors had been only five years earlier when the House Finance committee scorned him and his bill to require federal credit union insurance. For his part, Sundlun clearly relished presenting Nields and Baron as co-counsels. He outlined their accomplishments in a list of high-profile federal cases. “As a former federal prosecutor,” he proclaimed, “I have an absolute intolerance for corruption. If there have been insider deals, they will be exposed. If we find civil liability, we will sue. and if we find evidence of crime, Mr. Baron and Mr. Nields will recommend indictments. Starting today, the people’s demand for justice will be served.”

Teitz rose to speak. He dwarfed Sundlun at the podium and had to bend down over the bank of microphones. He promised gavel-to-gavel cable television coverage. “We will ask all the tough questions,” he assured the crowd, “and we will follow the evidence wherever it leads.”

Since January, Brown University President Vartan Gregorian and his faculty team had been poring over documents and interviewing RISDIC players. On a rainy Thursday in March, Gregorian delivered a 186-page report whose title played off RISDIC’s television commercials showing muscular hands sculpting a fierce eagle into granite while an authoritative voice promised security “carved in stone.” The cover displayed RISDIC’s familiar logo with the ironic title, Carved in Sand. This illusion of strength and invincibility, Gregorian said, “remained intact until RISDIC actually had to fulfill its function as an insurer for a major loss.”

The report singled out strong ties between lawmakers and the boards of RISDIC and its member institutions. Gregorian called the relationship “incestuous,” and his report noted: “Bills endorsed by RISDIC were received with favor; those opposed by RISDIC were not.” Gregorian criticized Arlene Violet for failing to press legislative leaders over Stitt’s report and faulted Atty. Gen. James E. O’Neil, who defeated Violet less than a year after she received the Stitt report.

Gregorian noted that during four years as attorney general, O’Neil had paid little attention to RISDIC. The report also blamed DiPrete and his Department of Business Regulation, which was responsible for bank examinations, for failing to communicate what they knew or do anything to head off the disaster.

Only days after banner headlines about Carved in Sand, Ira Chinoy reported in the Providence Journal that during six years as governor DiPrete had taken “a steady stream of contributions” not only from RISDIC itself but also from its insured institutions and from their officers. Several top players belonged to DiPrete’s $1,000 dinner club, giving them regular access. The reporter also identified $8,900 that Mollicone, the fugitive owner of Heritage Loan and Investment, had funneled into DiPrete’s campaigns. At least $29,000 had come from other officers of two troubled RISDIC institutions: Heritage Loan and the Greater Providence Deposit Corporation. Meanwhile, it came to light that Duffy & Shanley, the public relations firm that created RISDIC’s “carved in stone” commercials, had given $16,400 to DiPrete, who insisted that the connection was only “coincidental.”

“I don’t care how much they gave or didn’t give,” DiPrete said. “It didn’t do them any good.” But Frank Gaschen had told me that DiPrete had done nothing to support his 1986 bill to require federal credit union insurance. If RISDIC’s contributions “didn’t do them any good,” why had DiPrete apparently not lifted a finger during the next four years to prevent RISDIC’s collapse?

After her narrow 1986 loss to James O’Neil, Arlene Violet parlayed her legal training and gift of gab into a daily talk show on WHJJ-AM. Rapid-fire, she spoke with authority. Detractors had lampooned her as “Attila the Nun,” but in the wake of RISDIC’s collapse and Stitt’s report, callers treated her like a modern Joan of Arc.

Several times, she brought Bob Stitt to her cramped studio at WHJJ. On April 17, he arrived with a briefcase full of papers and went live with Violet after the 5 o’clock news. They were talking with Lou from North Providence when Stitt fell silent. He rubbed his eyes, then slumped over the counter on top of his documents.

Violet signaled for a break, rushed to him, wrapped her arms around him. “Stay with me,” she urged. “Come on, Bob, breathe!”

She shouted to call 911. doctors at Rhode Island Hospital pronounced him dead of a heart attack.

The inconvenience Anne and I experienced from RISDIC’s collapse never compared with the anguish of thousands who were locked out of their retirement funds. Our checking and savings accounts were frozen with our mortgage in the East Providence Credit Union, but our paychecks were drawn on commercial banks, and we opened new accounts at a federally-insured bank.

Just after Memorial Day, a rumor spread that the governor would announce a rescue plan for the East Providence Credit Union. I slipped into the State Room behind a crowd of reporters and dozens of people eager with anticipation. Members of Sundlun’s staff emerged from a door to his office, followed by legislative leaders from both the House and Senate. Sundlun strode in with four men I did not know and positioned himself at a lectern full of microphones. “Without a lot of preliminaries,” he declared in drill sergeant mode, “we have a deal to reopen the East Providence credit Union. We couldn’t have pulled this off without the cooperation of the people I’m about to introduce.”

The four were investors from Boston who had put together thirteen million dollars from private sources to take over the credit union’s modern building, properties, and portfolios. They would form a community bank under a complex agreement that Sundlun outlined. The deal would need approval by federal bank regulators and the Superior Court, as well as to be ratified by a newly formed depositors’ economic Protection corporation (DEPCO) that had custody over insolvent credit unions and banks. as the white-haired governor spoke, people sighed and relaxed. a woman in front of me wept silently.

“This is a good deal,” Sundlun rumbled. “It’s good for the depositors and good for the state.”

A few days later, DEPCO began making payouts to depositors at other RISDIC institutions that would never reopen. Newspapers printed the rules and conditions of repayment. The computations were complicated, but money finally began trickling back to depositors. A few grumbled that they were required to sign waivers absolving the state of further liability before they got their funds; others complained that they had more on deposit than DEPCO would repay. Thousands were in the dark about their accounts, worth an estimated $1.16 billion, still frozen in credit unions that would probably never reopen. Meanwhile, critics railed about the higher taxes needed to cover the bailout of RISDIC institutions that had been underinsured and poorly regulated.

Bruce Sundlun never projected sympathy well, and his repertoire did not include charm. Instead he came across as self-assured to the edge of arrogance. No sooner had the burdens of office landed on him than he became the target of taunts and jeers nearly every time he ventured into a public hallway at the State House. Nor did Sundlun seek sympathy. He had turned seventy-one during his first month in office but seized the RISDIC disaster like someone half his age. lights burned in his corner office long after the rest of the State House had gone dark. Gruff and abrasive, he seemed to harbor no doubts about himself or his mission. like Roosevelt taking office in the depths of the depression, Sundlun seemed sure his grit and gumption would triumph.

Early in the crisis, he bulldozed the General Assembly into creating what he called a depositors' economic protection corporation (DEPCO), which few understood. Sundlun exposed himself to blame by chairing DEPCO’s board as it seized the assets of credit unions that would never reopen. Depositors whose accounts were still frozen quickly forgot the insider loans and risky practices that had brought the system down as their rallies turned venomous against DEPCO and its creator, Bruce Sundlun.

As weeks stretched into months, Sundlun increasingly became the target of caricature and blame, even though RISDIC had declared itself insolvent before he took the oath of office. After June, when Rhode Island’s part-time legislature adjourned and stopped coming to the State House each day, Sundlun became the depositors’ primary target.

“I made a mistake,” Sundlun told a Providence Journal reporter. “I spent too much time encouraging these depositors groups to come up with these plans. We should have moved quicker and said, ‘The hell with you.’”

The bitter depositors returned his taunts on talk radio, picketed his house, burned a t-shirt from his campaign, and dumped its ashes on his doorstep. Their placards turned DEPCO into DEATHCO. Images of Sundlun with tiny mustaches like Hitler’s were a graphic insult to the state’s second Jewish governor. Sundlun admitted his annoyance but told reporters: “It doesn’t arouse a feeling in me where I want to strike back at the people who are doing it and hurt them. I’ve been Jewish all my life, so I’ve heard that stuff since I was in the schoolyard.”

Others attempting to solve the crisis inadvertently fueled the protesters’ rage. DEPCO mailed invitations for cocktails and dinner to its staff and the surviving workers at Rhode Island Central Credit Union, whose building the new agency occupied. But a copy of the invitation fell into the hands of Jack Kayrouz, the head of citizens for depositors’ rights, and he reviled the party as proof DEPCO was immune to the suffering of the depositors, taxpayers, and the elderly. On a sultry summer night, Kayrouz rallied a crowd of about 250 protestors at DEPCO headquarters in Warwick. Most were elderly; many were veterans wearing American flag pins on their jackets or caps. Yet the crowd crossed the threshold of civil restraint, spilling onto Jefferson Boulevard, a four-lane highway. Cars and trucks screeched to a halt. Horns blared.

“What do we want?” Kayrouz shouted.

“Our money,” the crowd roared.

“When do we want it?”

“Now!”

Most in the march had never engaged in civil disobedience, but they surged along Jefferson Boulevard and onto a nearby access road to Interstate 95. “We want our money,” they chanted as they tramped along. “We want our money!”

Police cars with sirens and flashing lights converged from all directions. There was no violence, but seven depositors were arrested, five of them over the age of sixty.

Depositors also began picketing Sundlun events. Hundreds protested outside Rhodes-on-the-Pawtuxet, where Sundlun and his political allies were scheduled to hold a black-tie reception for Ron Brown, chair of the Democratic National Committee. A quarter-mile driveway stretched from Broad Street to the hall, and depositors caught Sundlun in his Lincoln with Rhode Island license plate number one. They surrounded the car, pounded on its hood and roof, and splattered its windows with spit.

Sundlun shouted for his driver to stop. Through sheer determination he forced a car door open and stepped out into the hostile crowd. Aides and state troopers ringed the 71-year-old governor as he strode through the throng toward the hall.

Depositors spit at him. “Choke!” yelled one, waving a dollar bill.

“Choke,” the crowd shouted. “Choke! Choke!”

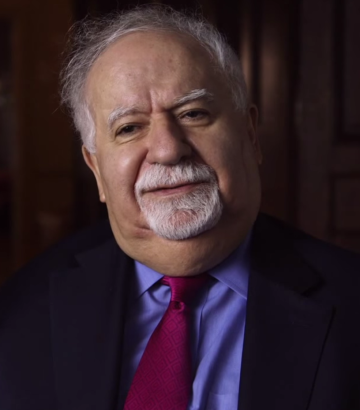

H. Philip West Jr. served from 1988 to 2006 as executive director of Common Cause Rhode Island. SECRETS & SCANDALS: Reforming Rhode Island, 1986-2006, chronicles major government reforms during those years.

He helped organize coalitions that led in passage of dozens of ethics and open government laws and five major amendments to the Rhode Island Constitution, including the 2004 Separation of Powers Amendment.

West hosted many delegations from the U.S. State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program that came to learn about ethics and separation of powers. In 2000, he addressed a conference on government ethics laws in Tver, Russia. After retiring from Common Cause, he taught Ethics in Public Administration to graduate students at the University of Rhode Island.

Previously, West served as pastor of United Methodist churches and ran a settlement house on the Bowery in New York City. He helped with the delivery of medicines to victims of the South African-sponsored civil war in Mozambique and later assisted people displaced by Liberia’s civil war. He has been involved in developing affordable housing, daycare centers, and other community services in New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island.

West graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y., received his master's degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York City, and published biblical research he completed at Cambridge University in England. In 2007, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Rhode Island College.

Since 1965 he has been married to Anne Grant, an Emmy Award-winning writer, a nonprofit executive, and retired United Methodist pastor. They live in Providence and have two grown sons, including cover illustrator Lars Grant-West.

Note that this online format omits notes which fill 92 pages in the printed book.