Bankrupt Central Falls Doled Out Raises To City Workers

Thursday, April 04, 2013

Despite deep cuts in pensions and other benefits, Central Falls employees will emerge from municipal bankruptcy later this month with something that is practically unheard of in the world of bankruptcies: raises.

“Raises are more unusual,” said James Spiotto, a Chicago-based attorney and a national expert in corporate and municipal bankruptcy. “That’s an interesting twist.”

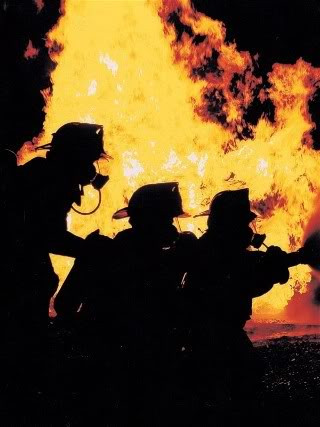

A review of the contracts negotiated while Central Falls was very much in the throes of the bankruptcy process reveals that the three major unions—firefighters, police, and other city workers affiliated with AFSCME Council 94—are set to receive on average 2.5 percent annual raises until 2016, when the contracts expire. The first round of raises took effect in July 2012. (See below tables for examples.)

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTThe base salary of a Central Falls employee is also higher now than it was before the city entered municipal bankruptcy in August 2011. The average base city salary at the time was $41,650. As the city neared the end of the process, one year later, the average base stood at $47,500, according to Gayle Corrigan, the chief of staff for the state-appointed receiver.

Raises called unfair

A leading taxpayer advocate called the raises unfair, given the sacrifices being made elsewhere in the city.

“While the residents of Central Falls suffer through a bankruptcy proceeding, struggle to repay the costs incurred from the bankruptcy itself, and lose a significant amount of equity in their homes, and while the Central Falls retirees have their pension slashed in half, it doesn’t seem that economic justice is served when working firefighters, police officers and city workers receive guaranteed raises averaging 2.5 percent a year over the next four years,” said Lisa Blais, spokesperson for OSTPA, a Tea Party organization.

Blais said the salary hikes raise the question of whether Central Taxpayers are also receiving raises in this economy.

For local property owners, their tax rates, at least, will increase by 4 percent annually over the next four years while a 55-percent slash in pension income takes effect for many retirees. The city workforce has also been shrunk from a pre-bankruptcy level of 174 to 117, as of this week, according to Corrigan.

In separate interviews, former receiver Robert Flanders and union officials said the raises were instituted as an incentive to keep city workers from leaving as a result of the numerous benefit cuts they took.

But taxpayer advocates said they remained unconvinced the raises were justified. Mike Stenhouse, the CEO of the Rhode Island Center for Freedom and Prosperity, said the raises were one example of the broad inequity between public and private sector pay found in a recent study the center issued. “We all want the government that works for all Rhode Islanders, not just some,” Stenhouse said. “I think this raise plays to that emotion.”

Officials: ‘Only half the story’

But officials who were on both sides of the contract negotiations said the raises had to be considered in the broad context of the deep cuts being made elsewhere in employee compensation.

“I think the opposite side of that story is there were cuts to each employee that were significant impacts to each employee’s life,” said Mike Andrews, the head of the city firefighter union, IAFF Local 1485. “To say that we got raises and that we made out I think is a misleading statement.”

Flanders largely agreed. “When you say they got raises, you have to put that in the context of what else why gave up,” he said.

The cuts were so severe that employees almost needed raises just to survive financially, said Michael Downey, president of Council 94.

Most severe were the changes to health care and retirement benefits. For firefighters, deductibles doubled from $2,000 to $4,000 for families and $1,000 to $2,000 for individuals—although city deposits into health savings accounts offset some of that. Co-pays went from 12 percent to 20 percent. And new rules on retirement mean that firefighters can’t retire before 57 and must have worked 25 years. Before, they could retire after 20 years at any age.

Other benefit reductions for firefighters included: dropping the annual clothing allowance from $1,800 to $1,000, eliminating the $10 per shift stipend for riding along on ambulance rescue runs, ending the $1,500 stipend for those who had EMT cardiac licenses, cutting two holidays, and shifting longevity pay from a percentage to a flat amount that cost firefighters anywhere from $500 to $1,000 annually, according to Andrews.

John Burns, the lead negotiator for AFSCME Local 1627, echoed those sentiments. “There were deep cuts,” he said, ticking off concessions on vacation pay, sick time, holidays, and health insurance.

Flanders and Corrigan pointed to other changes as well—the problem with disability pensions, in particular.

At one time, approximately 60 percent of firefighters and police officers were retiring on disability pensions, according to Corrigan. She said it was actually current employees who had taken the lead in proposing stricter rules on disability pensions. Those include distinctions between total and partial disabilities and counting out hypertension as a disability if it can be controlled with medication.

Cost of the raises

Blais said the pay raises beg two other questions: Do they exceed the $2 million that statewide taxpayers are contributing to the city budget? And, what are the costs of the new contracts compared to the old ones, before the bankruptcy?

Andrews said he was certain the total compensation of his members—once raises are weighed against all the cuts—had dropped overall, as compared with their compensation before the bankruptcy. Corrigan said she agreed. But neither was able to provide direct figures on the total differences in compensation.

When the contracts were settled, Corrigan said she had not done an independent analysis of the cost of the new agreements against the old ones. At the time, she said the paramount concern of the receiver’s office was the big picture: bringing the city to a point where its budget was balanced. By the end of fiscal year 2012, that had been achieved, according to Corrigan.

The dramatic restructuring that city departments underwent only further frustrates efforts to make independent assessments of the cost of the new contracts. For example, in fiscal year 2010, the budget for the Police Department was $2.8 million, according to the audited financial statements for the city. In the current year, the budget is $3.2 million.

But Corrigan said the Police Department is different today. She noted that it absorbed dispatch services, which previously were not included in the police budget.

She said it’s easier to make apple-to-apple comparisons in other areas, like overtime. And there records indeed show a significant decrease. In 2010, Central Falls budgeted $100,000 for firefighter overtime but ended up spending $408,000. In 2012, overtime had dropped to $116,974, according to Corrigan.

Reasons for the raises

Flanders said one of the issues he faced as the receiver for the city was how to retain a workforce with “radically different pensions.” He said he was committed to not compromising public safety in the process and said he was pleased that the city had been able to strike agreements with the fire and police unions, rather than outsourcing those services—an idea that was once considered by his office.

He also considers it an achievement that the city was able to reach agreements that eliminated so many abuses in the budget, such as overtime and disability pensions. On balance, he said the contracts were a “very favorable deal” for the city.

As it is, turnover is still high in the Fire Department, Andrews said. But without the raises, he suspects it would have been even higher.

He pointed to another reason for the raises. Before bankruptcy, he said Central Falls firefighters were the lowest paid among municipal fire departments in the state—a statement with which Corrigan said she agreed.

Burns said the raises emerged during the negotiating process. The specific 2.5 percent figure, he added, was put forward by the receiver’s negotiators.

A precedent for other communities?

The outcome of the Central Falls bankruptcy could set a precedent for others, especially any Rhode Island cities on the edge of the fiscal abyss.

Prior to Central Falls, the most notable municipal bankruptcy was Vallejo, in California, which filed in 2008. Unlike Central Falls, Spiotto said that he believes city employees in Vallejo did not emerge from bankruptcy with raises.

But Vallejo was still in the midst of bankruptcy when Central Falls went broke. “That precedent wasn’t available to us,” Flanders said. “We didn’t really have precedents to look to in terms of other communities.”

And Flanders added, Vallejo did not go after pensions to the same extent that Central Falls did.

“This really was terra incognita for all of us,” he said.

Stephen Beale can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @bealenews

Related Articles

- NEW: Central Falls Bond Rating Upgraded

- Central Falls Bankruptcy - City Reacts

- NEW: Central Falls Bankruptcy—General Assembly Leaders Speak Out

- Tom Sgouros: Why is Greece like Central Falls?

- Central Falls Mayor—Don’t Blame Me for Bankruptcy

- Municipal Bankruptcy: Who’s Next In RI?

- The Fall of Central Falls

- Chafee—Central Falls Bankruptcy a ‘Positive’ for Economic Development

- Will Central Falls Bankruptcy Damage RI’s Brand?

- Expert Says Municipalities Should Stop Threatening Bankruptcy

- 38 Studios Bankruptcy Hearing Begins Today: Company Owes $150 Million

- Is Providence on the Verge of Bankruptcy?

- 38 Studios Bankruptcy: Executives Say Tax Credits Could have Saved Company

- Ten Ways to Save Providence from Bankruptcy

- BREAKING NEWS: Central Falls Files for Bankruptcy

- NEW: RIPEC Report Finds Bankruptcy Might Not Solve Cash-Strapped Cities’ Problems

- Central Falls Mayor James Diossa: 13 To Watch in RI in 2013

- Can Woonsocket be Spared from Bankruptcy?

- NEW: Central Falls to Emerge from Bankruptcy