New Hope for Old Bones: Grace Cemetery––Architecture Critic Morgan

Saturday, April 24, 2021

Grace Church Cemetery on Broad Street in South Providence is more than a forlorn, seemingly abandoned burying ground. Rather, it is a template for a unique kind of urban green space, one that would serve as a park of memory and offer the possibility of a more whole neighborhood.

If anyone thinks about this cemetery at all, it is only as that wide place in the road, with hundreds of toppled and vandalized gravestones, a sad reminder of the struggles of somewhat less advantaged South Providence. Grace Cemetery, however, has a distinguished history and is a significant facet of the area's identity.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLAST

Grace Church is itself the pre-eminent ecclesiastical landmark in downtown Providence, with its towering spire. The parish bought land to bury its dead in 1834, only five years after building their first church. The original four-acre cemetery was later doubled in size in 1845, with room for 850 plots for noted Episcopalians, including the first Bishop of Rhode Island, John Prentice Kewley Henshaw, two governors and two United States Senators, one a nephew of Nathanael Greene.

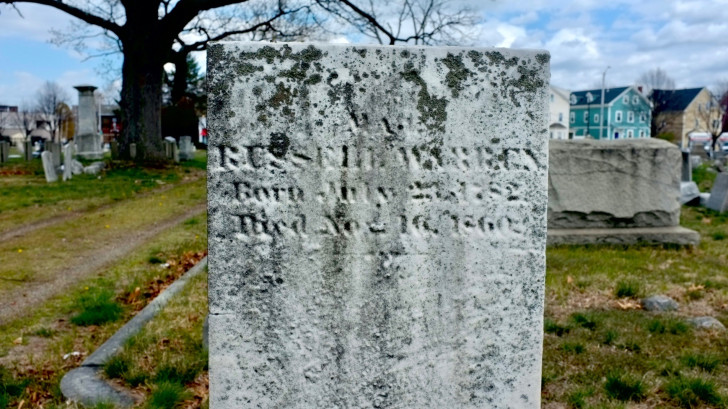

Buried not far from the bishop is Russell Warren, one of the leading Rhode Island architects of the early 19th century, who designed the original Grace Church, but is known for his co-authorship of the Providence Arcade. He built a number of Greek and Gothic revival houses in Bristol, Providence, and New Bedford, as well as Charleston, South Carolina. The charming gatehouse at Grace Cemetery, as well as the more lugubrious receiving tomb in a severe Greek style, is by Warren.

Around the time of the Civil War, Providence's first denominational burying ground began opening interments to non-Episcopalians. Along with abandoning the expensive practice of perpetual care, Grace Cemetery thus became more affordable and approachable. While mainstream Roman Catholics and Protestants were no doubt less welcoming, Grace became the preferred necropolis for Armenians, Blacks, Asians, and Eastern Europeans, and well as the South Providence Swedish community. And over 250 veterans from the Revolutionary War to World War II rest here.

Grace Church found it increasingly difficult to maintain the cemetery, so the parish has decided to focus on the living (their Matthewson Street Food Pantry is an example of Grace's community outreach). Maintaining the fabric of the church itself has proved exceptionally costly. So now, Trinity Gateway Historical Improvement Association, in concert with other neighborhood groups, oversees the fallow ground. But a couple of Saturday cleanups a year barely holds back the nibbling tides of neglect.

A possible path to the preservation of Grace Cemetery could be found in recent placement of a monument to honor the African-American soprano Sissieretta Jones, whose grave was unmarked for eighty-five years. The draw of the "greatest singer of her race" ought to be enough to create some sort of pilgrimage tour for mavens of Black music.

Sissieretta Jones could be the inspiration for other groups to discover, organize, and contribute to supporting other prominent figures and groups within the cemetery, whether minorities, veterans, or family patriarchs. Architects, for example, might band together to restore Russell Warren's eroding limestone monument.

Grace Cemetery could provide an entire curriculum and hands-on learning for preservationists involved in gravestone restoration. Landscape architecture students could begin the transformation of ratty grass and undernourished soil into the reflection of the green oasis that Grace was in the mid 19th century. Before there were public parks, picturesque garden cemeteries such as this acted as parks for urban dwellers.

Capt. John Martin, who died in Santo Domingo in 1802 at the age of 37. Slate stone with then popular funerary imagery of a neoclassical urns and weeping willows. PHOTO: Will Morgan

In short, Grace Cemetery could become a public park, with considerable greenery and horticultural richness to enhance South Providence. It could become a place to have concerts, community gatherings, and an outdoor market–think memory park, a neighborhood gathering point, and a public event space like no other.

This is the point where skeptics shake their heads. How will we pay for this? A revitalized Grace Cemetery refashioned into Sissieretta Jones Community Park, is a worthwhile expansion of the definition of infrastructure in President Biden's American Jobs Plan.

Such innovative solutions to urban blight ought to be part of the thinking and projected programs of our mayor and mayoral candidates. Grace Cemetery could become a national model for bringing urban cemeteries back to life.

Will Morgan is a landscape historian, a former editor of Landscape Architecture Magazine, and the author of American Country Churches.

Related Articles

- RI’s Celebrated Architect St. Florian Breaking the Code in Fox Point – Architecture Critic Morgan

- The Invasion of the Over-Scaled Buildings––Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- Brown’s New Policy Toward Old Houses –– Architecture Critic Morgan

- The Post-COVID Office –– Architecture Critic Morgan

- Urban Wish List – Architecture Critic Morgan

- RIPTA’s New Bust Shelters––Architecture Critic Morgan

- Post Pandemic Providence – Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- What Will Our Houses Look Like? – Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- CCRI Back to the Future – Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- Handsome New Apartments on Eighth Street – Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- Embracing Sidewalk Culture – Architecture Critic Morgan

- In Praise of the Post Office –– Architecture Critic Morgan

- The Best and Worst of New Construction on the East Side–– Architecture Critic Morgan

- Newport’s Most Fascinating Neighborhood – Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- Modern Master: Ira Rakatansky –– Architecture Critic Morgan

- Are We Designing Better Looking Parking Garages Than Hotels—Architecture Critic Morgan

- East Providence Is the Future –– Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- “What Can Brown Do for You?” University’s New Mega Project –– Architecture Critic Morgan

- Newport’s $100 Million Fixer Upper - Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- Brown Versus the Neighbors, Again – Architecture Critic Morgan

- A New Gateway for Pawtuxet Village – Architecture Critic Morgan

- Two East Side Apartment Blocks –– Architecture Critic Morgan

- Providence’s New Apartments: Wrong Building, Wrong Place –– Architecture Critic Will Morgan

- A Modest Proposal for Smith Street –– Architecture Critic Morgan

- Saving Newport by Destroying It? –– Architecture Critic Morgan