State Pension Fund Pays $570,000 to Raimondo’s Former Firm

Thursday, October 10, 2013

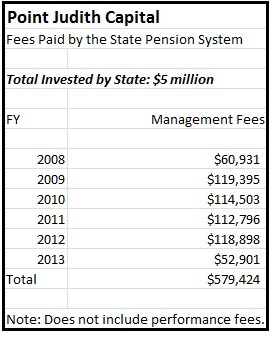

The state pension system so far has paid $579,424 to Point Judith Capital to manage nearly $5 million in assets, according to records obtained through a public information request submitted to the office of state Treasurer Gina Raimondo, a former partner in the venture capital firm.

In its response, however, the treasurer’s office declined to disclose any of the terms of its investment agreement with Point Judith, including the rate for the management fees the firm has been earning as well as Point Judith’s share in the profits, known as “performance fees.”

Sources: Point Judith earned higher fees

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTBut several sources tell GoLocalProv that the firm was paid at a rate significantly higher than the usual 2 percent. “It would be more than we normally pay,” said Marcia Reback, a former president of the Rhode Island Federation of Teachers and Health Professionals and a long-standing member of the commission. One source familiar with the deal, speaking on the condition of anonymity, pegged the rate at 2.5 percent.

In 2007, the commission committed to investing $5 million with Point Judith Capital. That amount gives the state a 7 percent ownership stake, as a limited partner, in the venture capital fund. (Point Judith had two funds, the state invested in the second one.)

Since its inception, in 2008, the fund has had an annualized internal rate of return of 6.2 percent, according to the treasurer’s office. Point Judith has earned nearly $580,000 off of the investment, while the state has received payments of $965,577, after all fees have been paid. “Seems to be expensive, doesn’t it?” Reback said.

The state did not invest all of its money at once in Point Judith. Instead it phased in its investment, meaning that for a few years, Point Judith was not responsible for managing all of the money. Nonetheless, state records suggest that the firm was paid a fee based on the entire amount of the investment, rather than the amount of actual assets it was managing.

A local investment professional confirm that practice was not out of the ordinary. “t is normal to receive a management fee on committed capital for a period of time and [then] transition to NAV [net asset value] management fees,” said Michael Riley, a principal in Coastal Management Group, which manages private equity investments and hedge funds.

(A former GOP Congressional candidate, Riley emphasized that he was speaking as an investment professional and that his comments should not be taken as indicative of his political leanings. He also noted that his firm doesn’t manage any pension assets.)

Normally, venture capital firms charge 2 percent management fees and 20 percent performance fees, similar to hedge funds. The management fees are based upon the entire amount invested, while the performance fees are the firm’s share of any profits earned when the companies in which the money has been invested go public or are sold.

When Point Judith appeared before the State Investment Commission it said it followed the standard 2-and-20 pattern, based upon a copy of its pitch book obtained by GoLocalProv.

Based upon the pitch book, Riley questions reports from other sources that Point Judith was paid at an unusually high rate. “I disagree they receive higher management fees. Again, the investment committee pitch book shows 2 and 20,” Riley said. He said to charge more than what was in their pitch book would have been a “dumb” move by the firm.

He also noted that the fee rate could not simply be calculated on the basis of how much in terms of dollars was actually paid to Point Judith. He noted that the actual dollar amount of the fees fluctuated year-to-year and pointed to a number of factors that could explain why that is, including early returns on closed investments and a transition from fees based on the amount of committed capital to fees based on the net value of the assets.

Based on the 2-and-20 fee structure, the Point Judith investment would not have been expensive, Riley concluded.

But smaller firms do sometimes charge management fees higher than the usual 2 percent rate, according to John Taylor, the research head of the National Venture Capital Association, a trade organization. “There are certain basic expenses any firm has, to attract and manage the best deals and to create the best outcomes,” Taylor said. For a larger firm, 2 percent management fees will cover those costs, but not a smaller firm, he said.

Questions about Raimondo’s background

But one Raimondo critic says the higher fees raise a red flag about Raimondo’s background and how her firm obtained the deal from the state. “The higher fee is just one of the questions—anomalies—that has come up in my review,” said Forbes.com columnist Ted Siedle, who is currently working on an investigate report on the state pension fund for AFSCME Council 94.

Siedle said it appears that Point Judith Capital got the deal with the state because of its partnership with the Tudor Investment Corporation, which at the time the partnership was announced had about $15 billion in assets under management. “So basically, she didn't have the credentials, the track record to merit the investment,” Siedle said.

Riley disputed Siedle’s characterization. “Point Judith did not lack for experience in 2007 when the decision was made to allocate state investment funds ….the bios and affiliation with Paul Tudor Jones show extensive background and experience… so I disagree,” Riley said.

He said the same goes for Raimondo’s personal qualifications. “I read her bio in the ‘pitch book.’ It’s very impressive. Maybe her health care focus and experience was unclear. I think she is extremely well qualified,” Riley said. (A state-redacted copy of the pitch book is linked below.)

Reback offered another explanation. “We were giving preference to Rhode Island firms,” she said, in an effort to support the local economy. “You know, it’s ‘buy local.’”

A call for comment to Point Judith Capital, which has since moved from Rhode Island to Boston, went unreturned yesterday.

Another hit to transparency

Ultimately, the state’s disclosure about the fees raised as many questions as answers about Point Judith’s fees.

In a September 30, 2013 letter signed by spokeswoman Joy Fox, the treasurer’s office said it was not required to disclose more information.

“The specific structure of the fees, expenses, and performance fees is considered proprietary information to Point Judith Capital. Rhode Island General Laws § 38-2-2(4)(B) exempts from disclosure information that contains, ‘information obtained from a person, firm, or corporation which is of a privileged or confidential nature.’ While we deem the actual amount paid … in management and performance fees to be public information, the limited partnership agreement is not a public document,” Fox wrote.

It’s not the first time the treasurer’s office has withheld information on investment management fees. In August, the treasurer refused to release information related to the state’s investment in hedge funds, prompting a letter of concern from a coalition of good government groups, including Common Cause Rhode Island and the Rhode Island ACLU.

Those advocates said Raimondo may be on firmer legal ground when it comes to the issue of its agreement with Point Judith.

“Based on RI Supreme Court decisions interpreting this provision of the open records law, the withholding of the fee structure information is probably allowable. Whether it should be withheld is another question. While there may be legitimate commercial reasons for keeping various details of the partnership agreement confidential, fee structure information may be one of those important pieces of data where state officials should, as they say, go ‘above and beyond … to provide additional transparency’ in light of the public interests at stake,” said Steven Brown, the executive director of the Rhode Island ACLU.

“However, I don’t know enough about the confidentiality concerns underlying these agreements to speak more definitively about it,” Brown added.

John Marion, the executive director of Common Cause, contrasted the transparency citizens expect from the government with the opacity one usually finds in the business world. “So when the government deals with the private sector that makes it a much more complicated issue because there is a whole different set of rules that apply to the private sector,” Marion said.

He agreed with Brown that the law may be on Raimondo’s side. He cited a 2001 state Supreme Court case, The Providence Journal v. Convention Center Authority. In its ruling the state judges invoked Critical Mass, a 1992 federal appeals court ruling that defined what confidential financial and commercial may be exempt from Freedom of Information Act requests. “We agree with the holding in Critical Mass and its progeny and adopt the test set forth therein, including the protection afforded to commercial and financial information that the provider would not customarily release to the public,” the state Supreme Court ruled.

In other words: if Point Judith Capital would not normally be required to produce a document, the state shouldn’t have to produce it on its behalf either.

“It’s clear that the Rhode Island Supreme Court’s interpretation of the state’s Access to Public Records Act is such that confidential commercial information can be withheld based on the Convention Center case,” Marion said. “It’s a trade-off we make to take advantage of these sort of investment partnerships. We wish the state didn’t have to make that trade off.”

Riley agreed that, ideally, the information on the fees should be made public. He added: “Raimondo’s office takes the position that when they invest as a limited partner in a private equity investment that their fee is negotiable and may vary from one limited partner to another. Terms can be waived by managers of the funds from time to time,” Riley said. “It may violate terms of that fund to reveal the fee structure the State has versus other limited partners.”

“I would also say [Rhode Island] provides as much if not more information than most state sites I’ve seen. The treasurer's office has done a great job,” Riley added. “I also think you guys have helped focus their efforts to the benefit of us all.”

Raimondo accused of double standard on truth, transparency

For public employees, the issue of transparency is personal. In an interview, Michael Downey, the president of AFSCME Council 94, took issue with the fact that Raimondo is still potentially earning money from the state pension system’s investment with Point Judith.

Before taking office, Raimondo resigned all her positions with the firm and put her any assets she had with Point Judith in a blind trust, a common way elected officials avoid conflicts of interests between their public work and the management of their private finances.

But Downey suggested that the blind trust is really just another limit on transparency. “It seems that the only thing that’s blinded is the truth to the taxpayer,” Downey said. “It’s high time that she tells the truth about it.”

Downey said Raimondo was employing a double standard. In her first year of office, Raimondo released a report on the pension system titled “Truth in Numbers.” That report became the factual basis for pension reform, which included the suspension of cost of living adjustments and other benefit reductions.

But Downey said Raimondo is only telling half of the ‘truth in numbers.’ “We know what we lost, but what has she gained?” Downey said.

Point Judith’s performance

Besides the amount in fees, the treasurer’s latest disclosure also revealed that the internal rate of return since the inception of the fund was 6.2 percent as of June 30, 2013.

Previously, Raimondo and her staff have provided different figures for what the rate of return has been. In an April 15, 2013 interview with WPRI.com Treasurer Raimondo said the “realized return” had been 22 percent. But in a correction to that story the Treasurer’s office said the “return” was actually 12 percent. Then, in a May 1, 2013 e-mail, the Treasurer’s office told a GoLocalProv reporter that the “annualized rate of return … was 10.9 percent as of June 2012.”

Riley said the key measure of Point Judith’s performance would be the “risk adjusted rate of return after fees.” But the treasurer’s office was unable to provide that in time for publication.

GoLocalProv also asked the treasurer’s office to reconcile the 12 percent figure with the 10.9 percent figure and explain whether the disparity in the two estimates was the result of an error or something else. The treasurer’s office declined to respond. “As explained in detail during our conversation, the above questions do not constitute a public records request,” Fox wrote.

Stephen Beale can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @bealenews

Related Files

Related Articles

- AFSCME Taps Forbes Finance Expert to Probe Hedge Fund Investments

- David Bettencourt Previews “Behind The Hedgerow”

- NEW: Caprio Splits with Raimondo on Hedge Funds

- NEW: Siedle Blasts Raimondo for Withholding Hedge Fund Info

- Rhode Island Steers Clear of Hedge Fund Trap

- EXCLUSIVE: RI Pension Investment in Raimondo’s Pt. Judith Had Steep Losses

- Should Raimondo Release Contracts with Hedge Funds

- Raimondo Receives up to $500,000 Payment from Pt. Judith Firm

- Ted Siedle: Hedge Fund Industry Loves RI Pension—For Good Reason