The Highest Taxed Fire Districts in RI

Thursday, December 06, 2012

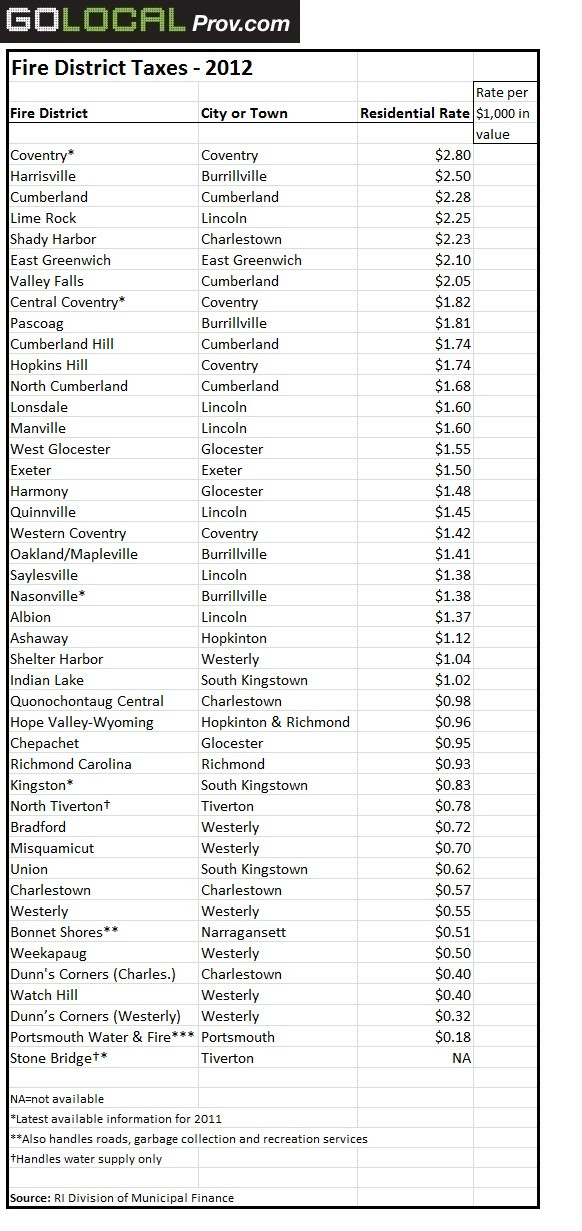

Fire districts tax their residents at rates that are all over the map, ranging from nearly $3 per $1,000 in assessed property value to as low as 50 cents or less, according to statewide data obtained through a public records request.

One fifth of the state population—about 200,000 Rhode Islanders—lives in an area served by a fire district rather than a municipal fire department.

Fire districts are autonomous units of government within a city or town that normally exist for one purpose: providing fire protection and related services. In all, there are 43 such districts, not counting the regular municipal fire departments as well as some all-volunteer fire departments that are scattered through the state.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTThe residential tax rates range from a high of $2.80 in the Coventry Fire District to 32 cents in the area of Westerly that is covered by the Dunn’s Corner Fire District.

In the Coventry Fire District, the owner of a single family home worth $200,000—the current median home price in the state—would pay $560 as compared with $64 for a home of the same value in the Westerly section of Dunn’s Corner. (See below tables for tax rates.)

The rates vary widely depending on whether a district has all full-time staff or a mix of full- and part-timers, public policy analysts at the Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council said in an interview. Other factors are the area covered by the district, the wealth of the community, and the range of services provided, such as whether EMS is included.

Case for consolidation

Many believe Rhode Island is ripe for the consolidation of its fire districts.

“For a state that’s [about] 45 miles long and a million people, we have more government organizations than we need,” said Gary Sasse, the long-time former head of RIPEC and also a former administration director under Gov. Don Carcieri.

A leading taxpayer advocate said the wide range in rates shows the particular need for consolidation among the many fire districts. “It’s just not efficient cost-wise or administratively for local cities and towns to be continuing to maintain separate fire districts. They should be consolidated into their respective towns across the board,” said Donna Perry, executive director of the Rhode Island Statewide Coalition.

“Regardless of the arguments you often hear from the fire districts that they are well managed and not creating extra layers of costs, the data shows that are simply not the case, they create a separate layer of taxes,” Perry added.

Does Lincoln need six fire chiefs?

The case for consolidation has progressed much further among fire districts than it has among school districts. So far, full-on merger efforts are underway in at least two communities: Cumberland and Lincoln.

Cumberland has five districts; Lincoln has six.

“In a town with six fire districts, if you were to consolidate, you wouldn’t need six fire chiefs. You wouldn’t need six tax collectors. You wouldn’t need six clerks,” said Mike Napolitano, the vice chairman of the board of commissioners for the Albion Fire District in Lincoln, and an advocate for consolidation.

Napolitano said the main impetus behind the merger is saving money. Beyond personnel, he said merging districts would cut costs on fire apparatus, which can run as high as $700,000 or $800,000 for a ladder truck.

Sasse agreed: he said consolidation should reduce overhead and allow fire departments to more efficiently use their resources.

But Lincoln may also be a lesson in how difficult consolidation can be. Three years ago, the town administrator, Joe Almond, held a meeting with officials from all six districts, encouraging them to consider consolidation. But most of them weren’t interested. Currently, merger talks are being held between just two of them: Albion and Saylesville. A third district, Lonsdale, was a partner to those talks for a while, but has since withdrawn.

One sticky issue in consolidation: how to deal with two different firefighter union contracts. An official at the Rhode Island State Association of Fire Fighters said his organization is open to consolidation—as long as collective bargaining rights are respected.

“No one knows what the details are until we get to the table,” said Robert Neill, a state representative at the state association and president of the Pawtucket Fire Fighters. “That’s the bottom line.”

Combining districts is more likely to win over the support of rank-and-file firefighters than creating a new town fire department, according to Napolitano. A new department means firefighters would have to re-apply for their jobs without any seniority to guarantee them a position. That problem is averted if the merged fire district remains independent, he said.

“Obviously if you don’t have the firefighters on your side to do this and they’re in a union, then you have a big problem,” Napolitano said.

When consolidation may not work

Consolidation may not be a taxpayer panacea, however, according to analysts at RIPEC.

John Simmons, the executive director, said consolidation has to be evaluated on a case by case basis. He said it may not be economical if consolidation involved one district with volunteers and one with full-time staff and the new district would be all full-time.

Consolidation could also backfire in cases where the collective bargaining agreements for the two districts have a significant difference in compensation—say a base salary of $40,000 in one case and $50,000 in the other. “Are you going to take a $10,000 pay cut or are they going to get a $10,000 pay bump?” said Ashley Denault, director of research at RIPEC.

If the merged districts adopt the contract with the higher compensation levels or a compromise between a higher and lower level, that could undermined the sought-after savings, according to Denault.

On the other hand, if the merged district opts for the cheaper of the two contracts, that could lead to resistance from the rank-and-file.

“It just isn’t very simple on the wage structure,” Simmons said.

Simmons said the greatest opportunity for consolidation or collaboration is in various office functions at the fire districts, such as information technology, human resources, and payroll.

Controversy in Central Coventry

One other advantage of consolidation, according to Sasse: accountability.

“People don’t live in districts,” Sasse said. “People live in cities and towns.”

Mayors and town councils, he said, have higher visibility than somebody elected to a board of commissioners for a fire district. And, with that visibility comes more public attention and accountability, according to Sasse.

He pointed to the Central Coventry Fire District as an example of what can happen when there’s less transparency and accountability.

This fall, it was suddenly revealed that Central Coventry had a $1.6 million budget deficit. Firefighters at the district went without pay for weeks and the district sought receivership. Now, it’s expected that the district will seek a significant tax hike to make up the shortfall.

Months before the budget flap, the district’s fire chief took a position in Smithfield, citing better organization in a municipal fire department as one of the reasons for his move. (Officials at Central Coventry did not respond to calls seeking comment in time for publication.)

Central Coventry currently has a residential tax rate of $1.82, making it among the top ten highest taxed districts, at least in terms of the residential rate. Local taxpayers fear the recent budget troubles could vault it to the top of the list.

And fire districts, unlike cities and towns, are not bound by the statewide property tax cap, making such wild swings in rates from one year to another possible.

Why tax rates vary so widely

Less dramatic factors account for most of the disparities in tax rates between districts in the same year. The differences stem from labor force, district size, and assets, according to Napolitano.

Does a district have all full-time staff or a mixture? Does it cover a large area with few properties? Does it serve a wealthy community? The answers could explain the variations in rates, experts say.

The wealthier a community is, the lower the tax rate needed to raise the same amount of money as a poorer community. That means that the district in the wealthier community may not necessarily be running a less expensive operation—it may just not need as higher a rate to generate revenues. That’s why Simmons and Denault say it’s important to also look at each district’s levies—defined as the amount they hope to raise in tax revenues. (The latest available statewide figures for levies are for 2006. A link to the levies is below.)

“All these districts run the gambit,” Napolitano said. “That’s why you see such a swing in the districts.”

If you valued this article, please LIKE GoLocalProv.com on Facebook by clicking HERE.

Related Files

Related Articles

- Warwick Strikes New Deals with Fire & Police Unions

- NEW: Senate Approves Update to State Fire Code

- NEW: Warwick Fire Department Receives $3.1 Million Federal Grant for New Hires

- Providence has Dished Out $22 Million in Police/Fire Overtime Since July 2010