Rescuing Providence: Part 2 - 0004 Hours Through 0230 Hours, a Book by Michael Morse

Monday, May 02, 2016

I always thought that a day in the life of a Providence Firefighter assigned to the EMS division would make a great book. One day I decided to take notes. I used one of those little yellow Post it note pads and scribbled away for four days. The books Rescuing Providence and Rescue 1 Responding are the result of those early nearly indecipherable thoughts.

I’m glad I took the time to document what happens during a typical tour on an advanced life support rig in Rhode Island’s capitol city. Looking back, I can hardly believe I lived it. But I did, and now you can too. Many thanks to GoLocalProv.com for publishing the chapters of my books on a weekly basis from now until they are through. I hope that people come away from the experience with a better understanding of what their first responders do, who they are and how we do our best to hold it all together,

Enjoy the ride, and stay safe!

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTCaptain Michael Morse (ret.)

Providence Fire Department

The book is available at local bookstores and can be found HERE.

Note From The Author

The adrenaline rush felt while driving toward a fully involved house fire in the middle of the night, past people running away from the inferno’s with what belongings they could gather carried on their backs is indescribable. The pungent smell of smoke gets heavier the closer you get. Running into a burning building that anybody with a rational mind would be running out of is something that firefighters live for. I’ve spotted ladder trucks next to burning buildings, extended aerial ladders and rescued people hanging out of windows. On cold, wintry nights on rooftops full of ice I’ve clung to precipices, straddled peaks and chopped holes to ventilate. I’ve forced open doors, or knocked them down and attacked fires from the inside. I’ve dragged inch and ¾ hoselines equipped with a Task Force Tips capable of discharging 50-350 gallons of water per minute through smoke filled buildings. I’ve felt the heat, then found the fire; it’s destructive power raging unchallenged and unstoppable, gaining strength... I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. Then, I was transferred to the rescue division. I was only supposed to go for six months. I found out that I wanted to stay.

0004

FRACTURED SKULL

“Rescue 3, a still alarm.”

The blow lights wake me before the PA system comes to life. I look at my watch through blurry eyes and am shocked to find that I have only been unconscious for 10 minutes—it feels like hours.

When a call comes in to the fire alarm office, the dispatchers, after sorting out the information from the caller, hit a switch on their console, beginning the process of dispatching the proper response. On our end, the first indication that we are going out is the activation of the “blow lights.” Every overhead light in the building is wired directly to the fire alarm office; when they trip the switch, the building goes from serene darkness to intense daylight. A few years of experience equips you with a sixth sense: a low hum, only able to be heard by some species of canine and rescue veterans, fills the air before the light blinds you. I feel the lights before they came on.

“Rescue 3, respond to 8 Stimson Street for a man bleeding from the head.”

I key my portable; I never had the chance to take it off my belt. “Rescue 3 on the way.”

I rest for a minute on the bunk trying to figure out if this is a dream or reality. Just in case I’m not dreaming, I slip on my shoes and head for the truck. Renato is already there, the motor running.

“I know where that is!” Renato exclaims. “My brother used to live over there. We’ll be there in no time!” I am refreshed by his enthusiasm. There is nothing worse than a miserable partner. With Mike leaving, I’m worried about my future on the rescue truck. Renato seems to be a great guy, but most young guys want nothing to do with rescue. The thrill of firefighting is something that understandably takes all the good guys away from EMS.

We ride to the call in silence. I silently ask myself why I do this. The money is better, but the real reason is because I am one of the fortunate few who can say that they love their jobs.

For 10 years I worked the engine and ladder trucks. I fought a lot of fires in that time and learned a lot. The adrenaline rush felt while driving toward a fully involved house fire in the middle of the night, past people running away from the infernos with what belongings they could gather carried on their backs, is indescribable. The pungent smell of smoke gets heavier the closer you get. Running into a burning building that anybody with a rational mind would be running out of is something that firefighters live for. I’ve spotted ladder trucks next to burning buildings, extended aerial ladders, and rescued people hanging out of windows. On cold, wintry nights on rooftops full of ice, I’ve clung to precipices, straddled peaks, and chopped holes to ventilate. I’ve forced open doors or knocked them down and attacked fires from the inside. I’ve dragged 1 3/4-inch hose lines equipped with a Task Force Tip capable of discharging 50 to 350 gallons of water per minute through smoke-filled buildings. I’ve felt the heat and then found the fire—its destructive power raging unchallenged and unstoppable, gaining strength, until it met me. I’ve given the order, “Turn in my line!” as flames rolled toward me and overhead, threatening to flash over, waiting for the pump operator to open the gate in time to release 90 pounds of pressurized water to the end of my line. I’ve knocked the fires down and waited for the smoke to clear. I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.

Then I was transferred to the rescue division. I was only supposed to go for six months, but I found out that I wanted to stay. Had I not spent 10 years on the frontline firefighting trucks, I never would have been able to change my career path. I still miss the smoke and fire, and someday I might go back. For now, EMS is my life. It is more suited to my personality anyway. Thinking back to my childhood and the dreams I had, it was the obvious choice.

The popular television show Emergency was my favorite show back in the ’70s. Johnny Gage and Roy DeSoto were my first role models. As early as I can remember, I wanted to do this kind of work. When we played war games as kids, I always wanted to be the medic. My vision of wartime heroism never involved killing the enemy; rather I dreamed of running through the rice paddies in Cambodia, bullets whizzing past my head, close enough to smell gunpowder, mortar rounds exploding all around me, with dead guys everywhere. Disregarding my own safety, I would go to the aid of my fallen comrades, taking bullets along the way, spitting out shrapnel and pushing morphine into the wounded soldiers. Once I killed their pain, I would carry the fallen on my back, using the fireman’s carry, back to the jungle and the safety of my unit. “Thanks, Doc,” was all that I needed to hear.

“Rescue 3 on the scene,” I say into the mike.

Engine 9 is already there. The victim is being helped down the front steps of his apartment house, a firefighter on each side, holding him up. Inside the house I see Arabic writing on posters adorning the walls. He has a towel on top of his head, covered in blood. It drips from the edges, onto his silk shirt and the sidewalk.

The officer of Engine 9 gives me his report: “Thirty-four-yearold male, smashed his head on a stone table, no loss of consciousness, but he has a huge laceration to the top of his head.”

“I can see that,” I say.

The patient walks into the truck, holding the bloody towel on his head and sits in my seat, dripping blood everywhere.

“You’re sitting in my seat,” I tell him, trying to mask my irritation.

“I don’t care; my head is splitting,” he replies with a MiddleEastern accent.

“Get out of my seat,” I tell him and point to the bench next to the stretcher. He reluctantly moves, mumbling something; I don’t care what.

It has been several years since 9-11, but the wounds still run deep. I am not proud of the fact that I look at this patient with disdain. I’m sure he had nothing whatsoever to do with the terrorist attacks on that day, but something residing deep within me comes to the surface and it takes every ounce of restraint for me to treat him with the respect I know he deserves. I have always prided myself on my fairness and respect for people of all races, religions, and sexual preferences. I don’t want to think poorly of this man, bleeding profusely from a serious wound to the top of his head, but I can’t stop it. It bothers me that I can’t see him as just another person who needs help. Something snapped in me on that beautiful September day, and I pray that I am not broken forever.

I have worn the turnout gear, Scott pack strapped to my back, and carried the irons and high-rise packs up numerous flights of stairs to fight fires on the upper floors of tall office buildings. I have felt the exhaustion from carrying equipment up flight after flight of stairs, wondering if I would have anything left when I finally get to the fire. Thankfully, I never felt what those New York City fire - fighters felt as they walked bravely up those stairs into heaven. Their sacrifice doesn’t fill me with pride in my profession; it fills me with rage at the people who perpetrated that heinous crime and continue to do so in the name of Allah. God damn them all.

That attitude isn’t going to help the guy in my rescue. I’m slowly becoming more rational when it comes to dealing with people from the Middle East. I truly don’t want the rage to live inside me any more.

The back of the rescue is very confined. Here, I am the alpha male—I need my space to be unspoiled. It’s not a lot to ask, one small corner in the back. I hate for it to be contaminated. This guy is off to a bad start. I spray my seat with disinfectant and wipe it with a clean towel before I sit and begin figuring out what is going on.

“What happened?” I ask.

“I tripped on a rug that I had rolled up in the corner of my kitchen. Before I could get my balance, I fell into the table. I hit my head. I’m losing a lot of blood.”

“I can see that. Renato, get a board.” I reach into the overhead compartment and grab a cervical collar. The device is collapsible, so I have to make some adjustments before applying it to the patient. Before I do that, however, I take a look at the injury. Lifting the towel from the man’s head, I see an enormous laceration, at least 12 inches circling the top of his head. I can’t believe that he wasn’t knocked out cold. I’m not mad at him anymore.

“I can’t believe you weren’t knocked out cold!” I say to him as I put the collar around his neck. Renato comes to the back door with a long backboard. I take it from him and put it on the stretcher.

“Here, sit here,” I say, pointing to the middle of the purple, hard-plastic board. The patient does as I say. I dress his wound with a trauma dressing, wrap his head with some gauze, and help him lie on his back. It is a little uncomfortable at first and then becomes unbearable. I lie to him as he grimaces.

“You will get used to the backboard. It only hurts for a little while.”

Renato takes his blood pressure and pulse, while I check his pupils and ask him a few questions.

“Do you know what day it is?”

“It is Thursday morning, the 8th of April at 12:30 in the morning.” he responds. He is more alert than I am, I realize as I look into his pupils and see that they are equal in size and reactive to light. I start an IV because Renato has informed me that his pulse is 124 and his blood pressure 130/90. The blood pressure is fine, his pulse irregular. A rapid pulse is indicative of a potentially serious head injury. I place a nonrebreather mask over his mouth and nose after setting the flow to 10 liters.

I hand Renato the EKG leads.

“White right, smoke over fire,” he says with a smile, reciting the age-old way to remember where on the body to place the EKG leads. The monitor’s green light glows and shows a sinus rhythm, rapidly moving along. I note “sinus tach” on the state report and record the other vital signs.

“You guys are all set,” I say to the members of Engine 9, who have waited outside the truck to see if they can be of assistance. If the situation had warranted, I would have needed one of their guys in the back with us to help with the patient and another to drive the rescue. But this patient is stable. Engine 9 goes back in service, and we go to Rhode Island Hospital. The patient’s wife locks the house and rides in the back of the rescue with us, holding her husband’s hand during transport. I find out that they are from India. He is a professor at Brown University, and she is a student. They are two young professionals in love hoping to start a life in the United States in the medical field, helping others. Damn those terrorists for turning me into a cynical bastard.

Things at the hospital are crazy. Elliot, a gentle-giant security guard from Alabama, is waiting outside the ER doors. He looks at our patient and shakes his head. Dressed in his security uniform and well over 6 feet tall and weighing 250 at least, he is an intimidating presence. It is unfortunate that the hospital has to hire security guards, but the city is a nut house, and all the nuts think this is their home.

We move our patient from our stretcher onto the hospital bed and wheel him in. Tonya is at the triage desk, waiting for my report.

“What do you have?” she asks, no nonsense in her demeanor. I am not fooled. She is a riot when given the chance. Nobody is better when the pressure is on, although she tolerates incompetence with barely concealed contempt. We have been through this hundreds of times and have learned to trust each other. I give the report; she assesses the patient, agrees with my findings, and starts the procedure of his care. This patient is going to the trauma room because of his unstable vital signs. When I return to the truck, Renato has cleaned and restocked it. We are ready for the next patient as we wheel back into the city.

We make it back to the station. Renato still hasn’t finished his dinner. It takes a while to learn to eat at rescue speed.

“If it wasn’t so busy, I wouldn’t mind staying on rescue for a while,” he says while shoveling cold stuffies into his mouth and dribbling clam chowder down his chin. “It’s a great way to learn the streets. I’ll lose some weight, too, if I never get a chance to eat,” he laughs.

“In six months on rescue I learned more streets than 10 years on the trucks. It’s different over here. You have a little more time to figure out where you are going. When a call comes in for a fire, you had better know where it is without thinking. There’s nothing worse than blowing a street and having a ladder truck and chief follow you down the wrong road,” I tell him, leaving out the fact that it has happened to me, more than once.

“Has that happened?” he asks.

“More than once,” I reply, hiding my grin by looking out the side window.

“Rescue 5 and Engine 2, a still alarm.”

“You have got to be kidding,” says Renato as I key the mike.

“Rescue 3 in service,” I say.

“Roger, Rescue 3. Rescue 5, you can disregard. Rescue 3 and Engine 2, respond to Route 95 North at exit 24 for an MVA.”

The stuffies and chowder disappear as we walk down the stairs toward the apparatus. Renato starts the engine, hits the lights and siren, and we are on our way.

0107 HOURS

MOTOR VEHICLE ACCIDENT

A highway response has its own set of potential problems. Scene safety is paramount. Every year firefighters and police officers are killed on the highways, struck by cars. At this time of night, the possibility of a drunk driver passing the emergency scene is great. I always tell my drivers who are new on the truck the same thing.

“Be careful—these people will kill you.”

“I know. We got hit on Engine 2 last week,” Renato says. “Some drunk slammed into the back of the truck and then took off. The funny thing was, his license plate got embedded in the truck’s bumper.”

“Bad luck for him,” I say. Sometimes the good guys get a break.

Engine 2 has arrived on scene and transmitted its findings.

“Engine 2 to fire alarm, we have a 25-year-old male, conscious and alert, complaining of neck and back pain, a laceration to his forehead.”

“Rescue 1 received,” I say into the truck microphone as we continue to the accident scene on 95 North. Traffic is light, the roads are dry, visibility is good, and there is only one victim. Chances are good that a drunk driver awaits us farther up the road.

“Rescue 1 on the scene.”

Engine 2 has blocked the two low-speed travel lanes by parking their truck across the lanes with its emergency lights activated. The State Police are on the scene, directly in front of the engine. A four-door sedan is stopped in front of the State Police vehicle, its nose imbedded in a guardrail. The air bags have deployed and the windshield is broken. I can’t tell if the air bag broke the windshield or if the driver’s head did. I plan on giving him a thorough going-over when I get him in the truck. I have seen hundreds of similar scenes over the years. The driver is standing next to the police officer, his arms waving around as he proclaims his innocence. Without even being in earshot, I know what he is saying.

“I was doing the speed limit and minding my own business. A big truck came out of nowhere and cut me off. He rode me right into the guardrail and kept on going. I only had a few beers.”

We stop the rescue in front of the victim’s car and walk over to him. Passersby flying past look at us instead of the road.

“What’s his story?” I ask the trooper

“He says he was cut off by a trucker who kept on going.”

“Has he been drinking?” I ask.

“A couple of beers,” says the trooper with a knowing smile.

“Are you hurt?” I ask the victim. He looks off into space.

“Hey, buddy, are you hurt?” I ask again, this time taking his arm and shaking him as I speak.

“I think so,” he responds.

“What do you mean, you think so? Are you or aren’t you?”

“I think so.”

“Get in the truck,” I say with resignation.

This guy looks wasted, but there is always the possibility of a head injury causing his lethargic reaction to my questions. We bring him to the back of the truck. Renato has gotten another long board from the side compartment, and we get him ready for transport. He complains about everything: the blood pressure cuff is too tight, the cervical collar hurts, the backboard is too hard, and on and on. When the state trooper comes to the back of the rescue to give him a ticket, the complaining really starts. His car will be towed to a garage, where it will be stored until he can retrieve it.

Engine 2 waits until we clear the highway to provide safety.

Renato gets in front to drive, and I finish in the back. The patient doesn’t give me any more information, but I have gotten all I need from the trooper. His vital signs are perfect, blood pressure 120/70, his pulse 68. He has a 1-inch superficial laceration above his right eye. His eyes are bloodshot, and he smells of booze. I put this information on the state report. Whether or not he is charged with drunk driving is up to the police. I hope he is charged. This guy could have killed somebody instead of ruining a perfectly good guardrail.

Renato takes the next exit from 95 North, makes a quick turnaround in Pawtucket, and gets back on 95 heading south toward Rhode Island Hospital. My patient lies quietly on the backboard, his neck immobilized by the cervical collar, and looks up at the ceiling. I look out the back windows of the rig, watching Providence glide by backward.

I hope the city sleeps until daybreak—I need the rest. Sometimes the rescue gods are kind; more often they are not. We make our way back to quarters, Renato to the dorm, me to my office. I am sleeping within seconds, I’m sure Renato is too.

“Rescue 3, a still alarm.”

0230 HOURS

SPLIT PERSONALITY

It feels like I have been sleeping for hours when the lights come on and the speaker starts to blare. The first words are indecipherable; luckily the dispatchers repeat the address a few times.

“Rescue 3, respond with Engine 15 to 174 Putnam Street for an emotional woman with a knife, bleeding from the wrists.”

Great. Just what I need. My 43-year-old body feels 65 as I stand, the pain in my creaky knees making its way up my back and into my shoulders. My joints groan as I put my rebellious body back into action. An hour’s sleep is a great nap but no substitute for a night’s sleep. Renato waits in the truck as I struggle down the stairs and into the rig.

Putnam Street is located in the Olneyville section of the city, about a mile down the road from Atwells Avenue and Federal Hill. The neighborhood got its name from Christopher Olney, who in 1785 operated a gristmill and paper mill there. Before that, Native Americans lived there and called their settlement Woonasquatucket, meaning “at the head of the tidewater.” In the 19th century, the area was one of the leading industrial centers in the country. After World War II, textiles became the driving force of Olneyville’s economy. Workers lived in two- or threefamily homes nearby. As the textile industry moved to the southern states, the jewelry industry took over. There were not enough good jobs to go around, and the population declined. The area was notorious in the late ’60s and ’70s as poverty and crime invaded the area. It still has a way to go, but recent improvements in the area have made it an attractive destination for immigrant families.

Engine 15 is with the police at our destination. The 15’s officer gives his report by radio: “Engine 15 to Rescue 3, we have a 46- year-old female, conscious and alert but suffering from delusions, minor lacerations to the top of her wrists.”

“Rescue 3 received.”

“What are delusions?” asks Renato as we approach the house.

“You are about to find out,” I answer. I have no idea what to expect.

The patient sits on a wooden chair in the middle of the front room in the first-floor apartment. The sheets being used as curtains are tattered and filthy, and clothes are strewn around the room. The smell of unwashed laundry and skin assaults my senses as soon as I enter the home.

“What’s going on?” I ask the patient. She looks at me without focusing her wild eyes on mine, crouches lower in the chair, and says, “Vicky is in charge; ask her.”

I look around the room for another woman but only see a skinny man sitting on a white couch in the other end of the room.

The couch he sits on has the look of a curbside sale.

“Where’s Vicky?”

“I’m right here,” answers the woman.

“Why are your wrists bleeding?”

“Because Doris is bad, and I want to hurt her.”

“Who’s Doris?”

“I put her away.”

“Where?”

“Way down inside me where she’ll never come back.”

It all comes together. Doris is either playing a dangerous game with us or she truly has a split personality.

“Can I talk to Doris?” I ask as the three firefighters from Engine 15, four police officers, and Renato look on.

“I’ll kill her if she comes back.”

“We are going to take you to the hospital so you can get some help,” I tell her. No use pussyfooting around. Any sign of indecision on my part would strengthen her delusions.

“I’m not going to a hospital! Vicky wants to play!”

I have to let her know she has no choice in the matter. I have a weird knack for talking sense into crazy people, probably from talking to myself for years.

“Vicky, you hurt Doris, and I have to get her to the hospital. I can’t leave her here with you, or you might kill her.”

“I like to play with knives,” she says and stands up. The police officers begin to move toward her, but I raise my hand and they stop. They want to end this drama as quickly as possible without having to restrain Vicky/Doris. They trust me and let me go on for a while. Vicky/Doris sits back down and begins to cry. She wraps her arms around her knees and rocks gently back and forth as she sobs. I close in slowly, attempting to gain her trust. When I am 3 feet away I stop, crouch to her level, and ask her, “Are you ready to get some help?”

“I’ve got Vicky in bondage. Let’s go before she escapes.”

That is music to my ears. Doris is back and cooperative, and Rhode Island Hospital is only five minutes away.

“Do you want one of my guys to ride with you in case she acts up?” asks Dick, the officer of Engine 15.

“I should be all right; there’s only two of them.” My answer lifts most of the tension from the room. Even Doris chuckles. The skinny man looks relieved, and the police begin to retreat. As we walk out the door into the chilly night air, Vicky returns.

“I like to play!” says our patient.

“I’ll take you up on that offer,” I tell Dick. Will, one of the guys from Engine 15, accompanies us as we ride through Olneyville, up Atwells Avenue toward Route 95. One of the police cruisers follows us to the hospital. Doris returns once we get rolling, sobbing most of the way. I will never know if the whole thing is an act or if she truly is sick. Psychological illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are relatively common. I have a feeling that Doris is in the manic stage of her bipolar disorder and playing with us. She has five firefighters, four police officers, and her skinny boyfriend catering to her whims for half an hour. Not a bad night’s work for the two of them.

All I know is that if I don’t get a little shut-eye my alter ego will appear. I am not proud of my behavior at times, especially when lack of sleep makes me impatient with people who call 911 for a ride to the hospital. It sometimes feels as though I’m being tested by the people of the city who seem to never sleep. Rescue staff are routinely called between the hours of midnight and six in the morning for sore throats, headaches, toothaches, nightmares, tummy aches, and the like. It comes with the territory, and I knew that before getting onto the rescue truck, but it still drives me crazy. Most of the time I handle the abuse well, but lack of sleep takes my perspective away. Most of the people who call us feel that their emergencies are the real deal, and I treat them accordingly. But there are times, thankfully not too often, that the long hours add up and I lash out at the people who have called for help.

The city feels quiet. I look forward to three hours of uninterrupted rest. Renato is full of energy and runs up the 24 stairs from the apparatus floor to the living quarters two at a time. Youth is wasted on the young. I use the railing to pull my tired, aching body up the stairs toward my office and into the rack.

I feel the speeding truck sway in rhythm with the winding road, the IV bag swinging back and forth with each turn, hypnotic if I choose to be captured by its spell. Moonlight filters through the back windows of the rig, illuminating the cramped space. I am alone with a dying patient. His silence is haunting; the only sound his labored breathing, which has turned from gasps to a death rattle. I fumble with the catheter, my hands seeming to hold the needle for the first time. Where is all the help, I wonder, as I butcher my patient’s arms with pathetic attempts to start a line. For the first time since I was a trainee, I feel panic. The lights flicker as the truck starts shaking, the speed too much to handle. I shout to the front for the driver to slow down, but nobody answers. The oxygen mask falls from my patient’s face, revealing his identity. He looks at me with piercing blue eyes I remember so well from my childhood. With surprising strength, he grabs my shirt with both of his hands and pulls me within inches of his face. The smell of beer consumes the tight space between us, another memory stirred.

“You never could do anything right,” my father says between dying gasps for air. There is no menace in his tone, just resignation. I feel his disappointment to the depths of my soul. If only I could have saved him from the cancer that ravaged his body 15 years ago he would have lived to see that I actually could do something right.

I lift him from the stretcher, shake him, and shout, “I did it, Dad. I’m going to be all right! I straightened out right after you died!” My words are too late, just as I was too late getting my life together.

He dies again, just as dead as that night 15 years ago when he died in my arms, convinced that I was a bum. The driver of the truck turns around. My mother, her face glimmering in the dull moonlight, says, “Killed him again,” as the truck careens out of control

Michael Morse lives in Warwick, RI with his wife, Cheryl, two Maine Coon cats, Lunabelle and Victoria Mae and Mr. Wilson, their dog. Daughters Danielle and Brittany and their families live nearby. Michael spent twenty-three years working in Providence, (RI) as a firefighter/EMT before retiring in 2013 as Captain, Rescue Co. 5. His books, Rescuing Providence, Rescue 1 Responding, Mr. Wilson Makes it Home and his latest, City Life offer a poignant glimpse into one person’s journey through life, work and hope for the future. Morse was awarded the prestigious Macoll-Johnson Fellowship from The Rhode Island Foundation.

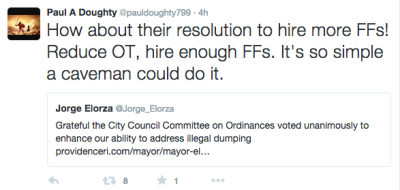

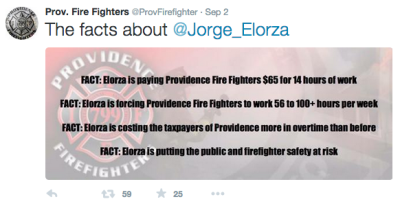

Related Slideshow: Providence Firefighter Tweets

Related Articles

- Starting Next Week: GoLocalProv Starts Publishing “Rescuing Providence” By Michael Morse

- Rescuing Providence: Part 1 - 0800 Hours Through 0840 Hours, a Book by Michael Morse

- Rescuing Providence: Part 1 - 1036 Hours Through 1339 Hours, a Book by Michael Morse

- Rescuing Providence: Part 2 - 1800 Hours Through 1946 Hours, a Book by Michael Morse

- Rescuing Providence: Part 1 - 1355 Hours Through 1646 Hours, a Book by Michael Morse

- Rescuing Providence: Part 2 - 2056 Hours Through 2233 Hours, a Book by Michael Morse

- Rescuing Providence: Prologue, a Book by Michael Morse