TRENDER: Artist and Teacher Leslie Hirst of RISD

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

Who are the Rhode Islanders leading in arts, fashion, food, and style? They're Trenders, and GoLocalProv offers glimpses of the people you most want to know on the scene. Today's Trender is Leslie Hirst, a visual artist from Pawtucket and a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Hirst is one of three recent recipients of a MacColl Johnson Fellowship from the Rhode Island Foundation. She accepted this distinction along with the 2014 Academy Award nominated animation artist and previous GoLocalProv Trender Daniel Sousa, along with future Trender contemporary artist Anthony Giannini. The Fellowships rotate on a three-year cycle between visual artists, writers, and musical composers. This award provides emerging and mid-career Rhode Island artists alike with a $25,000 grant to help them expand their crafts and to keep the arts alive and well within the Ocean State. Throughout her thirty-year career, Leslie has demonstrated impressive creativity, versatility, and adaptability in her paintings.

Hirst’s portfolio includes works such as: The Graffiti Project, Clover Paintings, Airplane Drawings, and Inhabited Landscapes. These creations span the last decade and illustrate Leslie’s ability to work with a number of different mediums to beautifully express truths about human life through a variety of diverse concepts, highlighting her refusal to be tied down to one idea. Hirst’s manipulation of the written word, as well as her depictions of human history and the physical world showcase this artist’s ability to successfully convey her desired messages through the use of several imaginative vehicles. During the months of November and December last year, Leslie was a resident at Yaddo, a retreat for artists in Saratoga Springs, NY. The pieces that she created during her stay with Yaddo are anticipated to be released sometime soon. In other recent career news, Hirst’s essay entitled “Groundwork” can be found at the beginning of a new book called The Art of Critical Making: Rhode Island School of Design on Creative Practice (Wiley) which investigates the creative process and the capabilities of the human hands. The grant which Leslie Hirst recently received will assuredly assist her to augment an already burgeoning career. Rhode Island residents should look forward to whatever the RISD professor can come up with next, and can view her entire portfolio via her personal website at: http://lesliehirst.com/home.html.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLASTWhen did you first decide that you wanted to become an artist?

It wasn't a decision at all, but rather a life that chose me. I've always been a maker, and have been particularly proficient with creating images as far back as memory takes me. The difficult part has been coming to terms with what that means.

How have your experiences as a resident in the state of Rhode Island and as a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design influenced your works?

It is a gift to be part of a creative community as rich as RISD's. It may be that those who have been here for a while don't recognize this, just as we become attuned to our surroundings, no matter how awe-inspiring they are. Because of the respected educational institutions in RI, there are swarms of creatives packed into a very small state. Yet, since this is not a state with a thriving art market, lots of stuff gets made here, but it does not get seen here. We (makers) simply tuck away in our studios and work in isolation, and that can be limiting for someone with a studio practice already underway who arrives in RI without knowing anyone. Not having the advantage of community that being a grad student would offer, you just kind of slip in and hope that someone notices after a while. The upside of this is that my exchange with students and fellow faculty is so meaningful. I could not see myself as a visual artist without being a teacher.

Can you speak a little bit about what inspired each of your major artistic ventures – starting from Inhabited Landscapes and culminating with your Graffiti Project?

I like that you mentioned that I refuse to stay “tied to one idea," but it is more like a refusal to label what I make as painting or drawing or object. My ideas follow pretty consistent paths. I can easily identify the precise tipping points that have ignited every project - all of them have come from highly nuanced thinking - but those points are only visible to me in hindsight. I just spend my time in conversation with my ideas, disregarding limits or categories, letting things pile up, and eventually something rather odd gets stuck in there.

When I began Inhabited Landscapes, for instance, I was writing a thesis on the spirituality of place while I was also working in the studio on two 6 x 8 foot oil on canvas paintings depicting a type of infrared aerial surveillance image of suburban housing tracts. My technique was messy and required lots of solvents, which I scraped away to create cartographic grids. In the midst of this, I got bit by a dog in my hand - a puncture wound that went all the way through from my palm to the back of my hand. I certainly couldn't get into chemicals and solvents with this injury, but I needed to get some new work out for an upcoming show. There were several wood rings in my studio that I had cut from a pine tree earlier that summer. I originally intended to carve them and use them for woodcut prints, but sitting there in my studio, unable to make my big paintings, I thought: "why do I want to print this wood when what I am really interested in is the wood, itself?" So, I got out a tiny brush and began those pristine little paintings.

It's funny: every body of work that I've explored began because I was doing something else. We don't look at art that way - we only see what it is and not what it was intended to be or what it came from.

What lies behind the abstract meaning of your Graffiti Project? What comment do you believe this eye-catching collection makes about contemporary society?

I love history and artifacts. They help us get to the "why" of something. I'm not necessarily talking about things in a museum or vault. I collect everything, and I'm drawn to practices of embellishment and ritual as heightened forms of routine. On top of this, my relationship with type and graffiti is a long one that extends from interests in Illuminated manuscripts, advertising design, Roger Dean album covers, Japanese calligraphy, as well as 16th and 17th century needlework. I used to keep these things in separate compartments, and now I simply let them all exist together. That's what we do today. Everything is a meld.

It always feels strange to say that I am influenced by graffiti because I do not make tags and pieces, but rather, I appropriate them. I find a wall of graffiti as infatuating as a fresco by Giotto or a painting by Raphael. The good stuff (graffiti) adheres to design conventions of proportion, balance, and continuity. It is all about the body: arcs of the shoulder and elbow in relation to the core, yet it is not a free-for-all of movement. Graffiti writers spend time working out their designs so that these motions are trained, ingrained and consistent. Because I am also an athlete, I've thought about the links with this type of body training to the skilled penmanship of eighteenth and nineteenth century scribes or Asian calligraphers. I've thought about the encryption that graffiti writers engage with to obscure their identity and to distance their designs from legible forms of written communication. I've thought about how the look of something changes our interpretation of it, and the amplified distance between signifier and signified. I've thought about the role of the hand-written word in our digitally driven communication platforms and the congruencies of binary code with needlework. I just let it all come together. It's all the same thing.

Where did you find the tags which appear throughout these works?

I find good and bad pieces and tags all over the US and Europe. I haven't been to many other parts of the world - I'm certain that there are plenty more. But I prefer old-school rail graffiti due to the imposed restraints of the surface and the fact that the material structure of railcars is not significant for historical preservation. Rail graffiti is clumsy. And rail provided the means to move these designs around. I'm amazed to see pieces by a single writer popping up in so many regions and covering such an expanse of time. I've become a bit of a scholar, although I've never knowingly met any writers. I always have a sketchbook with me. And I've photographed the trains that sit along the I-95 corridor between Providence and Pawtucket several times.

I was especially taken back by your piece entitled, “Nana”, which is composed of watercolor, dye, and fittingly – spray paint. Can you talk a little bit about this specific work of art?

More than once, someone has asked me about that work. They want to know where I got my lace. I made it up, and it is not lace at all, but rather a swirl of the word "NANA" painted over and over in watercolor. There are other elements in there, too, such as a little girl's bus ticket and a hand-written business document composed in French. The "NA" crew is big in Paris. When you start seeing it written over and over on those old, stone rail walls, it looks like a taunt: na na na na na.

How do you choose which mediums to use in each of your individual paintings?

I don't generally begin my work with a medium in mind. It always grows from thoughts and actions that accumulate through play or curiosity. I understand that many songwriters work this way, too, beginning with gibberish and sound before thinking concretely about language or form. Maybe "play" is a deceivingly fun word. Sometimes it is painful and goes beyond having a conversation with materials – it is more like wrestling with them. For instance, it was a completely ridiculous thought to make paintings with four-leaved clovers, but that's what they looked like to me: little units that form a larger composition. Do you have any idea how hard it is to adhere dried plants into a painting? I wasn't conscious of choosing to do it. I just had to figure it out.

What artistic endeavor of your own are you most proud of? Which one required the most work?

That's a tough question. The most difficult work is always the next one. Starting something can be daunting. As artists, we begin with a vocabulary that we have developed over time, and mine feels obvious to me but is not necessarily evident to others. I've always admired painters who pursue structured systems for their applications. They know their materials and applications so well that composition becomes the driver for every new work. I have worked on continuing series in the past, but because I concentrate so much on what that material has to say about that application, I eventually reach the point where the work feels burdened and strained by structured applications. Besides, I always seem to be more interested in the residue or leftovers of what I am making instead of the thing that I set out to make (such as the wood rings). All of this is dependent upon keeping my eyes wide open to everything I am doing and thinking about, and freely inviting anything into my process.

What did you get out of your stay with Yaddo at the end of 2013 and what did you work on while you were there?

I gave myself two incentives when I arrived at Yaddo: the first was to begin anew and to not pick up with anything that I had previously begun; and the second was to work with some beautiful, hand-made Japanese paper that I had been given several years ago. I was also reading Jorge Luis Borge's El Jardin de senderos que se bifurcan, which includes the essay "The Library of Babel." Thinking about the twenty-five orthographic symbols that Borge's describes in this essay, and how these symbols contain the whole of universal knowledge through order and arrangement, I began developing my own set of repeating calligraphic symbols that overlay and obscure one another.

What is great about being in a community of artists like Yaddo is the conversations that arise about creative practice and process. Composing, whether it is a drawing, a chapter, or a musical score, is as much about what is not there as what is. Some days I would destroy entirely what I had created over the previous days. There were days when I (and each of the residents) made nothing at all but rubbish. It is necessary.

How do you plan to use the money which was granted to you by the Rhode Island Foundation through the MacColl Johnson Fellowship?

I'm finishing an artist's book that I started five years ago. I'm upfitting my studio so that I can be more productive. Also, during my sabbatical, I will be traveling to locations, art collections, and institutions that are meaningful to the conceptual underpinnings of my work. Part of this travel will take me to Venice, Italy, where I will work during a two-month residency over the summer. Finally, the money will help me to develop some projects that have been brewing for years. This is such an amazing gift for an artist like me who has never had extra resources to pursue experimental work.

And, I'm looking around for a venue to exhibit my work.

What are some of your anticipated future projects? Can you tell us about the topics and the mediums which you plan to employ in these upcoming works?

I'm working on a proposal for an installation that uses water - specifically, the reflections of water - as the primary material. This is a project that combines the visual and verbal language of materials, and it will be the first completely site-specific work that I have embarked upon. It may take more than a year to work it out. Everything that I do takes a long time.

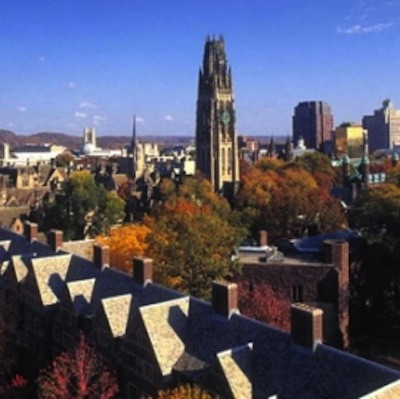

Related Slideshow: New England Colleges With the Best Undergraduate Teaching

U.S. News & World Report released a survey conducted in 2013 of college administrators on the best schools for undergraduate teaching. Several New England made their lists for best National Universities, Liberal Arts Colleges, and Regional Universities. See which schools made the lists in the slides below:

Related Articles

- TRENDER: Accordion Master Cory Pesaturo

- TRENDER: Fashion Designer Kate Brierley

- TRENDER: Observatory Design’s Cutter Hutton + Ayako Takase

- TRENDER: Architect Christine West

- TRENDER: Glassblower and Metal Worker Kim Vredenburg

- TRENDER: Photographer + Jeweler Nancy Reid Carr

- TRENDER: Artist + Writer Scott Simmons

- TRENDER: Green Penguin Electronics’ Benjamin George

- TRENDER: Rockstar Body Piercing’s Jef Saunders

- TRENDER: Artist Toots Zynsky

- TRENDER: Midday Records’ Davey Moore

- TRENDER: Sculptor Boris Bally

- TRENDER: Author Stefana Albu

- TRENDER: My Little Pony Illustrator Mary Jane Begin

- TRENDER: Tattoo Artist Mike Boissoneault

- TRENDER: Chef Ben Sukle

- TRENDER: Natural Science Photographer Diana Brennan

- TRENDER: Warren Jeweler LeeAnn Herreid

- TRENDER: Chorus of Westerly’s Andrew Howell

- TRENDER: New Urban Arts Director of Programs Emily Ustach

- TRENDER: Wilbury Theatre Group Artistic Director Josh Short

- TRENDER: Academy Award Nominated Animator Daniel Sousa

- TRENDER: Educational Game Designer Alan Tortolani

- TRENDER: Newport Architectural Historian John Tschirch

- TRENDERS: Lily Ricci + Victor Bartash of Cape Commons Brewing Co.