Theater Review: Trinity’s Clybourne Park

Friday, October 21, 2011

I recall, more a decade ago, sitting in Trinity’s Lederer Theater and watching a young Conservatory student named Jennifer Mudge Tucker on stage and thinking: this girl has it.

Last night in the same theater, I took in a 3rd-year Brown/Trinity Rep MFA student named Mia Ellis on stage. As I watched this young actor embody the controlled postures and tightly smiling deference of a Black domestic in 1959 with mature grace, I had the same happy epiphany.

This girl has it too.

Appearing in Trinity’s new production of Bruce Norris’ Clybourne Park as Francine, a Black maid in suburban 1959 Chicago, Ellis brings a taut warmth to her creation, her resonant alto modulated and sweet, yet revealing in just the right places the irritation, fatigue, and impatience with the racism surrounding her. Later, Ellis appears as Lena, the flip-side to her 1950s domestic--an educated, forceful, and fed-up woman in 2009 with a preening and controlling husband, 3 children offstage somewhere, and the necessity to get down and dirty to make her discomfort clear to a modern-day round of racism.

Mia Ellis: nuanced, memorable

The writing for both these roles is good, but what makes Ellis’ characterizations so memorable is her remarkable nuance of physicality and voice. Further, she displays not one bad acting habit, and in so young a talent this is a rarity. Finally, Ellis possesses the ability to mute her beauty, to make it go quiet in service of her character. When her Lena reveals the coarse punchline of a simultaneously sexist and racist joke, she flattens her face, makes her mouth go ugly, and stares, hard. She’s as ugly as the humor she’s wielding.

Clybourne Park and A Raisin in the Sun

In the first half, a white middle-class couple (Bev and Russ, played by Anne Scurria and Timothy Crowe) fraying from the suicide of their adult son are packing to leave Clybourne Park, the fictitious Chicago neighborhood created by playwright Lorraine Hansberry in A Raisin the Sun. Raisin follows a Black family moving to Clybourne Park. In Norris’ first act, Bev and Russ are the couple selling, unwittingly, to Hansberry’s Black family. Well-meaning vicars and less-well-meaning neighbors reveal this conflict and simultaneously prod at the weighty intransigence of Bev and Russ’s grief.

The second half of Clybourne Park leaps forward a half-century and this time, it’s a white couple (Mauro Hantman and Rachel Ward) who’ve bought into Clybourne Park, which we learn had been taken over by Black families, experienced urban decay and crime, is on the upswing and just the kind of place a well- (or not-so-well-) meaning white couple would look to buy, tear down, and rebuild.

Everyone is racist

But the Black couple in the room (Ellis as Lena and Joe Wilson, Jr. as Kevin) represent Clybourne Park’s neighborhood association in a pat turning of tables, challenging the architectural encroachments of the white couple’s new house design. Lawyers stir up the action this time around, and soon everyone is calling everyone a racist. Or a sexist. Or a homophobe.

It’s a simple mirror set-up, and while the play is sold as a darkly comic bitter pill with harsh truths, the fact is that Clybourne Park feels a bit light for all that. The writing lacks the Klieg-lamp brutality of Pinter or Patrick Marber (whose play Closer set the bar for what people want but will never have the courage to say to each other). And Norris' apparent respect for the seemingly-easy-to-imitate but impossible-to-equal rhythms of David Mamet has inspired stretches of multi-character staccato patter that just doesn’t work. It’s not the production. It’s the writing.

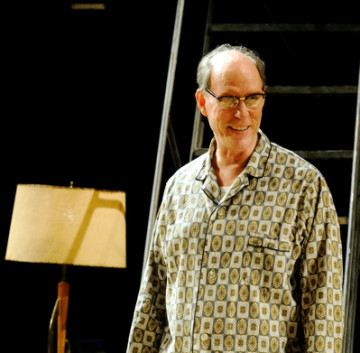

Timothy Crowe: masterful stillness

Nonetheless, the play moves well enough to keep us interested, particularly in the first half. Here, though, the dramatic momentum comes not from racial tension, but Russ’ mounting anger at the emotional incursions of his neighbors, vicar, and wife. And here, actually, is the other great note of this production of Clybourne Park: the performance of Timothy Crowe.

This gifted, increasingly grizzled mainstay of Trinity’s repertory company has brought a veteran stillness that beautifully echoes the nascent control of Ellis’ performance. Crowe’s Russ has to simmer for nearly an hour before he boils over, and Crowe gives us just enough foreshadowing in the nuance of the quickening of his reply, the fix of his grin, the tightening of his shoulders. It is a master turn, and his doubled role in the play’s second half, a delicate bit as a contractor, avoids every obvious note and makes you miss him when he leaves in search of a tool.

The young Ellis and the aging Crowe, in fact, although they barely share a dozen lines in direct interaction, anchor what is best about Trinity’s Clybourne Park. Two actors--one entering her career, one peaking in his--show us how humans struggle against control. How a maid refuses, with her voice, to accept a silver chafing dish forced on her by her employer, or how a father defends, with a glare, the right to his grief. This is reason, doubled, to see Clybourne Park.

Clybourne Park, through November 20, at Trinity Repertory. For more information/tickets, call 35-4242 or go to www.trinityrep.com.

Related Articles

- Theater Review: The Good Doctor at 2nd Story Theatre

- Theater Review: A Doll’s House at The Gamm Theatre

- Theater Review: Brown/Trinity’s Threepenny Opera

- Theater Review: Paul at The Gamm Theatre

- Theater Review: Trinity’s His Girl Friday

- Theater Review: Poe, at Trinity Rep