Good Is Good: Where Have All the ‘Mad Men’ Gone?

Thursday, April 28, 2011

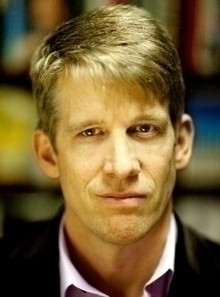

Tom Matlack is the former CFO of the Providence Journal and is the founder of The Good Men Project, a non-profit charitable corporation based in Rhode Island and dedicated to helping organizations that provide educational, social, financial, and legal support to men and boys at risk.

It’s ironic if not downright bizarre that viewers have become obsessed with the highly stylized version of 1960s Madison Avenue when the ad world of today is, in all reality, a world of true desperation for some of the most creative and well-liked men in the industry. Men with families, fancy degrees, and packed resumes that didn’t have to rely on Don Draper’s lies to build a reputation. And yet, none of that mattered when they faced into the teeth of a dying industry and the vestiges of what’s expected of us as men:

“You could just feel it coming down. You could just feel everyone’s assholes getting a little tighter.”

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLAST“And then I got this little beep on my phone.”

“The HR person came in with her hatchet, and closed my door.”

“It’s not you. It’s not your work.”

“She looked at me and said, ‘we’re letting you go.’”

So begins a very different sort of story in the film Lemonade, the true story of unemployed ad men trying to make the best of it. There are no three-martini lunches, no sign of men being able to weasel their way into a new job at another glitzy agency. While Lemonade shows the lucky ones—the guys (and a few gals) who got out of the ad business and were able to launch careers where they could reinvent themselves, others are not so lucky. For every story of reinvention, there are ad guys with missed mortgage payments and cars in hock, guys with a roomful of trophies who can’t get them a job because they aren’t “digital natives”—the new and rising superstars in a business turned around.

♦◊♦

Jack Crumbley still lists the Good Men Project on his Facebook account. His Twitter account lists Tehran, Iran, as his (fictional) home town and provides the following self-description: “Writer, creative director, Irish bouzouki player & supervised lunatic.” His website, “Call Me Jack,” is still up. The “about me” section is particularly humorous:

Jack’s long career in advertising started at McCann-Erickson Worldwide, then on to a position as creative director and partner at a company which later became Holland Mark Martin (the Martin being Jack’s middle name). In the late ’90s, he worked as a freelance advertising writer; most recently, he was a partner at the firm of Martin Randall. “He was always the same, a very kind and generous person with a generous and easy smile,” says friend Arch Di Peppe. “He did write brilliantly,” notes another, Ben Adams, “and always kept up a splendid series of emails.”

But in a world where reality doesn’t always reward the résumés and the talent, Jack took his own life on August 23, 2010.

♦◊♦

For every woman who commits suicide, four men will do the same.

The higher rate among men is a worldwide phenomenon. And while a recent report from MRC clinical scientist Dr. Ciaran Mulholland states that the reasons for this are far from clear, many of the proposed explanations share a common feature: the changing role of men in society. Men often have a more stressful time in achieving educational goals than in the past and are now less successful in this regard than women. Financial independence comes at a later age. Work is much less secure now; periods of unemployment are the norm for many. The psychological threat of unemployment is at least as harmful as unemployment itself. The suicide rate has been shown to rise and fall with the unemployment rate in a number of countries. In the recent recession, a full 82 percent of job losses have befallen men, according to a story in The New York Times.

It is also surmised that men are less likely to recognize that they are under stress or unhappy, let alone ill. And perhaps it’s therefore less likely that the rest of us can see the signs of trouble in other men and reach out to help them.

♦◊♦

One of my best friends in business school at Yale was a guy named Joel. He was brilliant, able to ace the most advanced finance classes without studying. He had a certain elegance about him. Some mixture of ancestry gave him long, jet-black hair, piercing eyes, and swarthy good looks I admired with more than a little jealousy. We often went running together after class was over—me huffing and puffing and Joel seeming to glide along, barely breaking a sweat, at a pace that threatened to kill me.

Like me, Joel got a summer job on Wall Street between his first and second year of business school, but he decided to do something that to him was more rewarding. He fell deeply in love and planned to marry. The last I heard he was working an important consulting job for Amtrak in Washington, D.C. Knowing Joel, he was probably some kind of special assistant to the whole thing, charged with turning a billion-dollar deficit into a surplus for our national rail system.

Then I got the call that he had been found in his apartment with a bag over his head.

His death shocked me so much I refused to believe it. His family held a memorial service on Capitol Hill. I didn’t go. I asked my mom to instead. She said the family really hadn’t been able to grasp what had happened yet. They still talked about their son as if he was alive.

♦◊♦

The opening credits to Mad Men show a man free-falling, his world literally thrown out from under him. With all the talk of glass ceilings for women trying to get in and up in industries such as advertising, I wonder whether there’s a glass bottom for the men who are discarded.

Advertising is about style and looks and creative directorships. Being in the center of the capitalist universe is an oft-coveted spot. But a career falling apart in the recession has nothing to do with perceptions and everything to do with humanity and manhood as it’s situated in 2011. In the worst of scenarios, it can be a continued grinding down of who we think we are supposed to be as male providers and thinkers and doers, and the reality of how increasingly hard it is to maintain that façade. Openness and honesty, talking about the real issues, getting past the façade—without judgment, without censoring—is the way we can get beyond the Mad Men glitz and into what’s real.

For more of Tom's works, as well as other pieces on related topics, go to The Good Men Project Magazine online, here.

If you valued this article, please LIKE GoLocalProv.com on Facebook by clicking HERE.

Related Articles

- Good is Good: Adultery’s Double Standard

- Good is Good: Are Women’s Colleges Outdated?

- Good is Good: Men, Faith and Goodness

- Good is Good: What Men Say to Themselves (When No One’s Listening)

- Good Is Good: The Illusion of Success for Men