Good Is Good: Being a Good Man Has Nothing To Do With Feminism

Thursday, July 05, 2012

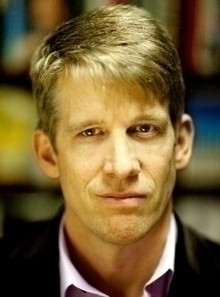

Tom Matlack is the former CFO of the Providence Journal and is the founder of The Good Men Project, a non-profit charitable corporation based in Rhode Island and dedicated to helping organizations that provide educational, social, financial, and legal support to men and boys at risk.

Here’s the basic axiom: power conceals itself from those who possess it. And the corollary is that privilege is revealed more clearly to those who don’t have it. When a man and a woman are arguing about feminism—and the women involved happen to be feminists and the man happens to be an affluent white dude—the chances that he’s the one from whom the truth is more obscured is very high indeed. That’s as true for me as it is for Tom Matlack.

– “Words are Not Fists” BY HUGO SCHWYZER

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLAST♦◊♦

“No fucking pictures!” the captain screamed. Soldiers have gotten violent with me when their comrades have been killed. I took a few frames then put the camera down and started helping to bandage the most badly wounded soldier. He had taken a lot of shrapnel, and his face looked like hamburger. We checked his torso for wounds, but there were none. He was pleading, “Doc, you got to give me something. I can’t take this pain. I can’t take it.” His friend was lying dead against his legs, but he didn’t know it. He couldn’t see through the blood in his eyes, and he felt nothing but the stabbing pain.

The scene was eerily quiet, save for a radioman calling for a medevac. A minute later, the soldier’s sobbing began to mix with the birdcalls in the stifling, still air.

I slowly walked over to the captain and told him that I was going to do my job and that he could take my cameras later if he wanted. He nodded to me, maybe knowing that no one was going to move through a minefield to stop me anyway. I walked among the wounded men, shooting as I went and trying to lend a hand where I could. Platoon members carefully put the wounded onto litters and carried them to a landing zone for the helos. Then four young men lifted the dead soldier’s torso gently into a body bag. One bent down and began to rip the gear off his comrade’s flak vest. Then he thought better of it, reached up, and quietly zipped the bag closed.

– Shooting The Truth BY MICHAEL KAMBER

♦◊♦

The end result is an unshakeable feeling that Tom and the men he claims to speak for are simply angry that their unquestioned male privileges are being eroded. It’s not that men are being edged out of the conversation at all, but that women are beginning to have a say that appears to be the problem. Watching privilege erode, even slightly, can be disconcerting for the privileged. But the bare minimum of being a “good man” is not conflating the erosion of your privilege with genuine oppression. The good men I know in my own life enjoy the challenge of shedding sexist stereotypes like “nagging wife” and “naughty man-child” to enjoy going forward with women, hand-in-hand, as equals and as friends.

– As Equals and as Friends BY AMANDA MARCOTTE

♦◊♦

One day, after I started going to the seminary, I was walking toward the chapel when up ahead of me a guy got stabbed really badly. Everybody just kept walking. “It ain’t none of your business,” someone said. Guys were jumping over the body and the pool of blood. When I got to the man he was bleeding out onto the floor and, I swear to God, I could not walk over that blood. It was like something was pushing me to look at this man, look at what was happening here. Guys were like, “Yo! Yo!” But I could not move. All I could do is say, “This shit has to stop.”

The guys looked at me like I was crazy; at one time I was involved in half the stabbings at the prison. They started swearing at me, saying, “What the hell are you talking about?”

I said it again: “This just has to stop, man. We have to stop killing one another.”

Everything changed for me at that moment. Finances didn’t matter anymore. It didn’t matter if I traveled around the country, or if I could do whatever. It didn’t matter. It was like, how do I not help people? How do I not stop and look at the humanity in each person, man? How do I recognize that these are all God’s children, man? And how do we become part of that human family so that we don’t kill each other?

I got the guy up off the ground and got his blood spattered all over me. The guards came running to us and got me out of the way. They didn’t question me because they saw what I had done. They thought I was crazy for helping this guy.

– Blood Spattered by JULIO MEDINA

♦◊♦

A few months ago I was interviewed by Tom Ashbrook, of NPR’s show “On Point.” I am a frequent listener to Tom’s program and have always admired how he can talk about controversial topics—from abortion to Middle East peace to Presidential politics—and remained inquisitive without bias. That’s what makes his show go. He gets people from both sides of an issue and is great at getting them to explain themselves clearly while letting listeners decide what they think without spoon-feeding them an answer.

I was excited to meet Tom and talk about the Good Men Project at the Boston Book Festival before a live audience that numbered well over 800.

Everything was going fine, I was telling my story and the story of our Project, when something remarkable happened.

I was in the middle of explaining the national context in which GMP sees the need to clarify what is going on with men. I referred Hannah Rosin’s headline grabbing article and book by saying, “And then you have female sociologists saying that men are over. If you think about it, if a male sociologist came out and said women were over we’d all be criticized for it.”

What I thought was a pretty non-controversial point.

Ashbrook cut me off to say, “We did that for like 5,000 years.”

I kept rolling, talking about the importance of feminism and how in a way what we are talking about at GMP is feminism in reverse: women were trying to get out of the house and men are trying to get back in as fathers and husbands.

But inside I was boiling. The guy who I thought never took a stand had just slapped me down. Hard. He’d made clear that any conversation of manhood had to be premised on an acknowledgement of the primacy of feminism in that conversation.

It caught me so off-guard that it was only in watching the video of the interview that I really appreciated the depth of his taking a side, something I so respected him for not doing, on the issue closest to my heart.

Quite honestly it made me want to puke.

♦◊♦

My formative experience as a man came as a recovering alcoholic. In church basements there is a very clear message that men help men and women help women. Falling in love is not going to get your sober. There are plenty of mixed sex meetings but in the end I always found myself gravitating towards all male meetings. And I had a series of male sponsors who saved my life.

On a daily basis I heard men tell a deep and painful truth about themselves that stirred my soul, made me cry, and often laugh at my own lunacy. After a lifetime of hating myself as a man, bit by bit I began to see that I was not alone and that in fact I might be able to live my life in a different way. My first sponsor often told me that the psychic change required to transform a hopeless drunk into a sober and recovering alcoholic starts in the head but ultimately happens in the heart. What happens when one drunk tells another the truth about themselves is that both the teller and the listener are forced to look in the mirror. And drop by drop what they see moves from the head into the heart. It’s an agonizingly slow process for most, but in the end the soul itself is transformed and the man who couldn’t put down a drink or tell the truth about anything becomes a useful member of society.

For years I went to South Boston to sit in a room full of men very far away from my Yale degree and venture capital firm. The guys I met had done hard time. They’d hit bottoms just as painful as mine but often much more tragic. They wore ink and gold and spoke with thick accents often with poor grammar. But what I learned in that classroom (the meetings were held in a school) was that all my book smarts didn’t mean shit when it came to my life. I wasn’t going to think my way out of my problems. I had to listen to what these guys were telling me. And in a fundamental way they have figured out stuff about themselves that I had just begun to examine.

The bond I felt in those rooms was palpable. It wasn’t anything like the way I saw men portrayed on TV or in the media. These were total strangers who had every right to hate me but instead, loved me unconditionally. They taught me how to take responsibility for my actions, how to tell the truth, and how to stay sober. They taught me to aspire to a completely different kind of goodness than I had ever contemplated in my prior shadowy world of immobilizing fear and quick fixes. They taught me the courage to look deep inside for the answers, to help another man no matter what, and feel my emotions.

Could any of that have happened if women had been in the room with us? Absolutely not. Did each man in that room leave with the very direct intention, reinforced by their brothers, to treat women categorically better than they had before entering? Absolutely yes.

♦◊♦

As the founder of The Good Men Project I’ve spoken about manhood well over a hundred times by now, in places as diverse as a treatment facility for teen prostitutes to a Hollywood premier. Inevitably the question comes up: “Yeah, this is all really interesting but what exactly does it mean to be a good man?”

At the beginning I would bumble around with a long-winded explanation about the importance of personal narrative, moments of truth in every man’s life, and the infinite possible definitions of goodness.

Now I just say that I don’t know.

I can see the disappointment in people’s eyes. They want some magical formula for being a good father, husband, and man.

I usually go on to explain that I am not a particularly good man. I aspire to a personal goodness that I have caught glimpses of through my own path to manhood, including plenty of blood, sweat and flat-out failure.

♦◊♦

My son Seamus goes to a Jesuit High School. I was brought up Quaker, so anything with a direct pipeline to Rome is highly suspicious in my book (not to mention having a close friend who was a victim of sexual abuse at the hands of a priest). Over the last four years I have come to greatly respect my son’s teachers and the Jesuit institution he attends.

The cornerstone of everything that goes on at my son’s school is the simple concept of becoming a man for others. On parents’ night I talked to his biology teacher who made clear that they would indeed learn some biology in his class but the real topic was manhood. On Veteran’s Day the teacher made all the students interview a veteran on videotape and come into class and do an oral report on what they learned. More than once, Seamus’s biology homework the weekend was to do two hours of service work.

This last spring break Seamus and a dozen classmates went to the Dominican Republic on a service trip. They went to the Haitian border to witness men attempting to buy life-saving food to save their families before having their bags of rice slit by border guards. They held deformed children in an orphanage. They sat with kids who spent their life picking metal out a huge trash dump. And they helped plant coffee in a subsistence hill village.

Certainly this idea of compassion for those less fortunate is an appealing one when thinking about male goodness. But even service, as the charismatic woman who led my son’s trip explained so movingly, is about personal connection. It comes from the heart not the head. So you can’t tell someone else how to do it, only try to listen to your own soul.

♦◊♦

My original motivation in founding the Good Men Project had little to do with what I thought men should do and more in realizing what we were lacking. What I saw in myself, and many of my male contemporaries, was a sense of confusion and depression over the male landscape. And I also saw a lack of conversation about what was really going on just under the surface for men in a very wide spectrum of circumstances.

My goal was not to proselytize in any way, shape or form. It was simply to bring individual stories of manhood to the surface in hopes of inspiring others to share their stories and, while doing so, become better men. That, in the end, is how it has always worked for me. An abstract discussion of manhood is boring as dirt to me. Listening to a guy spill his guts is transformational. At least to me.

And when I started The Good Men Project, it happened for me again. I sat with Julio Medina as he told me about being a Sing Sing inmate for years until he picked up a friend who had been stabbed off the prison floor and in that moment changed forever. I traded hundreds of emails with Michael Kamber from the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan and ultimately the day his best friend, Tim Hetherington, was shot and killed taking combat photographs. I met Ron Cowie at an outdoor café and listened to him weep as he retold the story of losing his wife to a rogue virus. As he wiped away his tears, their toddler daughter asked for a bagel.

These stories, and scores of others like them, changed me forever. They made me a better man. They gave me more insight into how to connect man-to-man in ways that are too often shunned by us collectively. I don’t know whether it’s by nature or by training, but men who reveal such personal stories, particularly those including failure and sadness, is, in my view, far less common than it should be.

I may not know what being a good man is but I am quite sure that a key part of any process to figuring it out is a deep level of honesty and self-revelation that we all too often pass on for more superficial pursuits.

♦◊♦

So how does all this relate to women and, more specifically, feminist doctrine? I know I led with that big headline and have made you wait to get to the heart of the matter. But since I know this topic causes a lot of people to lose their minds, I wanted to at least explain the path by which I found myself in this feminist sinkhole.

Going back to being a man for others, the clear implication of that goal is the “other” is generally someone who needs your help and may in fact be less fortunate. That most certainly includes orphans in the DR and teen prostitutes at the Germaine Lawrence School right at home in Boston. And God knows it means, just to me now, looking at the way that race, gender, sexual orientation, and wealth play into systematic discrimination and oppression.

I have often said that the conversation amongst men about what it means to be a good father and husband has obvious benefits for wives and mothers. The aspiration is to figure out how to do and be better men, and that means in relation to the women in our lives.

But here comes the problem. The stories that transformed my life where not told by women. They were told by men. My fundamental view is that there is a male experience that is too often squashed in our society by a culture that perpetuates a deeply flawed view of manhood. What I hope to do is not dictate what replaces that simplistic view of what it means to be a man, but simply create the space for a more nuanced discussion.

♦◊♦

The most disappointing, and in fact dangerous, aspects of the Good Men Project’s success, in my view, has been the extent to which we have been sucked into a debate over gender theory in general and feminism in particular. Whether or not you agree with any of the wide variety of definitions of feminism, the Good Men Project is not about gender theory and it certainly isn’t about feminism. Or at the very least that was never my goal in founding it.

I realize to some that the litmus test of being a good man is being a card-carrying member of a strident form of feminism that puts the burden of proof on every male for the sins of their brothers. But to me that is the most extreme form of the same old nonsense which keeps men from searching their souls for what manhood is really all about, to them. If you define manhood purely from a female perspective most guys are just going to turn off. And in my view, rightly so.

That’s why it saddened me to engage in such non-productive debates with the likes of Hugo Schwyzer, Amanda Marcotte, and Roseanne Barr who all attacked me for saying that being a dude is a good thing.

Perhaps even more significant than my fist fights with feminism over manhood has been the steady stream of highly trafficked pieces on our site about the female view of men, from gas lighting (one of our most popular pieces ever—“Why Women Are Not Crazy”) to the constant drum beat of posts in which manhood is viewed in the context of gender theory. Stuff like, “On Women’s Rights: Yeah, Yeah. Blah, Blah. Whatever.” And “A Rant.” And “Five Ways Feminism Helps Men.”

None of this is to say that a healthy debate of feminism isn’t a valid enterprise and one that is important. It just saddens me that it has become such a core part of what we are doing at GMP.

To be crystal clear what I wanted most is a nationwide discussion of manhood and god knows we have sparked that. We have over 400 regular contributors and a vibrant community of readers and commenters. In the end I do not decide what gets published nor do I even moderate comments. I am a sometimes contributor and very interested reader. There’s a team of amazing people behind the scenes making the magic happen. And you, the readers, first and foremost decide what you want to talk about. If nothing else the web is a purely democratic vehicle. I can say that I want you to read first person accounts of men at war, in prisons, and recovering from addiction but unless you read those stories we won’t likely do a lot more of them.

I have often said that the demographic which I most want to reach is not the guy at any extreme but the non-famous father, husband, and worker trying to figure out what the heck is important to him whether he is a venture capitalist (like me) or a stay-at-home dad or an inmate or a soldier coming back from Afghanistan.

I just have a really hard time seeing how debates over gender theory advance the ball in that guy’s thinking. Sure pretty much every discussion of manhood involved a discussion of sexuality and men as they relate to women, but a man-to-man discussion of those topics, in my experience, is very different than one set up to be in the context of a woman’s point of view. It may very well be that it ends up coming to conclusions very in line with what feminists believe but the process is a very different one.

I often think of Kent George, one of our originally contributors whose story I read for the first time early one Saturday morning while drinking my first cup of coffee while still in bed. I almost fell out of bed because I was laughing so hard. And that was before I started crying. His story is about being beat up physically by his older lesbian sister and abused verbally by his Irish Catholic mother in working class neighborhood of Boston. The story is funny because of the gender reversal and the way he tells it. But in the end it’s sad because it’s clear how much damage Kent suffered and also how much compassion he has for his mother, who he later found out had a profound mental illness, and his sister.

What’s the feminist moral to that story? I don’t know. But I do know that Kent is a damn good man and his brutal honesty, and humor, inspired me to be a better man and treat the women in my life the best I can no matter what the circumstance.

♦◊♦

I had a female at GMP read an early draft of this piece and her response stopped me cold:

Here’s the thing — and you may not like me very much for this.

—Women shouldn’t be in the conversation about men IF women are viewed by men as sexual objects instead of just people.

—Feminsm’s whole reason for being is to stop women from being viewed as sexual objects.

To me — it’s as simple as that. And so a phrase like — “In church basements there is a very clear message that men help men and women help women. Falling in love is not going to get you sober.” — reduces women to “the other” — someone who cannot be helpful because they are the ones you either fall in love with or have sex with.

And I just don’t get that.

The reason it stopped me cold is that in my AA example, I did not distinguish by gender. My language was intentionally gender neutral. The reality is that new sober alcoholics of every sexual orientation and gender behave the same way—they’d prefer to take a hostage and have sex than do the real work required to get and stay sober.

But the female reader assumed that I was viewing women in this context as sexual objects even though the words that she quoted quite clearly didn’t say that and in fact that is not the case at all—men and women are both grabbing for anything to fill the hole of addiction.

So even a colleague who has read countless pieces I have written and I think understands what I was getting at slapped me just as hard at Tom Ashbrook. And completely without merit.

The further discussion I had with the reader was around this idea of single sex discussions and whether or not my going into Sing Sing with Julio on the first stop of our book tour to meet with a room full of men sentenced to life would have been different if a woman was present. I tried to explain why I thought an all male conversation was different than a mixed gender one: “It’s about a level of honesty that men wouldn’t reveal with a women there.” She responded:

I’d love to know WHY that is. And I think so many women are interested in GMP because they want to know why also. That’s the crux of everything. Honest discussions about the difficult issues. And … If men can’t be honest with women, and men are the ones in power … I think that is part of what feminism is also.

It is the crux of the issue indeed. This idea that just because men want to have a discussion about manhood on their own terms that they are lying to women about it. There are plenty of forums for women to talk about men. I have made my way over to Jezebel more than once and gotten my ass handed to me.

What happened in that classroom in South Boston and in the bowels of Sing Sing with those inmates was a kind of man-to-man honesty that benefits women but isn’t going to happen if the frame is feminism or, when men are grappling with the deepest darkest secrets of their lives, if women are present. At least for me, there’s a kind of deep bonding that happens when a guy looks me straight in the eyes that is different than a similar conversation I might have with a woman. The transformation is only possible when I see that I am fundamentally not alone in my struggles to be a good man.

I don’t know but I expect women feel the same way. There are plenty of all women support groups in recovery and out in which I am quite sure men’s presence would disturb the safety of the boundaries established by the group.

All of this isn’t to say that the GMP should be a single sex forum. Far from it. Women are welcome for sure. But to my mind if the topic strays from a discussion of manhood in men’s own words to a feminist critique of manhood, my initial inspiration and hope for the Project is completely lost.

♦◊♦

From a macro perspective The Good Men Project was founded just as The End of Men went to print and the likes of Tiger, Charlie Sheen and John Edwards hit the front pages. In other words just as most men I know, and the thousands I met during the course of working on GMP, were digging deep for real answers to the questions about meaning and importance as a man, our whole gender was getting thrown under the bus.

According to the media we are less employable, less educated, inferior stay-at-home parents, and sexual deviants to boot. We are really good at going to jail, leading our country into meaningless wars, and taking down massive financial institutions.

The stereotype of what it means to be a man actually crystalized into a narrower stick figure as the ground under our collective feet gave way.

I look at the revolution in the work and family life patterns of men as not the end of men but the birth of something new and better. That is what GMP is all about: exploring that potential from every possible angle. And why viewing manhood from the perspective of a feminist wrecking ball, that leaves every one of us men guilty of gender oppression, a death spiral in my view.

In the end I think we all want the same thing: a new kind of macho in which men are allowed to express themselves as fully formed human beings who change diapers, are capable of intimacy, do meaningful work, and aspire to goodness in whatever way they define it.

But I refuse to see the world with a reductionist lens that dismisses the possibility that men can have their own stories of struggle for goodness that can be shared man-to-man in a way that changes the teller and the listener alike quite apart from what a woman or a feminist might say about that story.

For more of Tom's works, as well as other pieces on related topics, go to The Good Men Project Magazine online, here.

If you valued this article, please LIKE GoLocalProv.com on Facebook by clicking HERE.

For more Lifestyle coverage, don't miss GoLocalTV, fresh every day at 4pm and on demand 24/7, here.

Related Articles

- Good Is Good: When I Was a Bad Dad

- Good Is Good: 10 Reasons Men Should Cook

- Good Is Good: Do Teen Boys Want Love, Not Sex?

- Good Is Good: Father of the Grad

- Good Is Good: Should Boxing Be a Women’s Sport?

- Good is Good: Macho Men

- Good is Good: What Do Men Really Talk About?