Good is Good: What I Learned (Again) from Dr. Seuss

Thursday, January 20, 2011

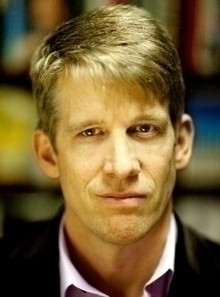

Tom Matlack is the former CFO of the Providence Journal and is the founder of The Good Men Project, a non-profit charitable corporation based in Rhode Island and dedicated to helping organizations that provide educational, social, financial, and legal support to men and boys at risk.

I was announced as the new Chief Financial Officer of the Providence Journal with operations all over the country and over 3,000 employees. I was 30 years old and had proven myself gifted in behind-the-scenes manipulation. However, as the public face of perhaps the most important company in the state, my new role would place me in full view.

I panicked.

A week after the announcement, I stood at a lectern in an empty Brown classroom on the east side of Providence. A middle-aged woman, the head of Brown’s drama department, sat in the front row. She had a smile as big as the great outdoors; a large pair of reading glasses dominated her beady eyes. “Go ahead,” she said. “Read your financial report like you were presenting to a bunch of Wall Street analysts.” I didn’t bother to explain that we were a private company. My heart felt like it was going to bungee-jump out of my chest. I couldn’t breathe. When I opened my mouth, I simply spat out a few words, hyperventilated, then mumbled a few more. I was about to be exposed.

GET THE LATEST BREAKING NEWS HERE -- SIGN UP FOR GOLOCAL FREE DAILY EBLAST“Okay, that’s enough,” she said, walking to the lectern where I was sweating profusely. “You can’t speak and hold your breath at the same time, Tom.”

For the rest of the session, she had me do nothing but breathe in and out.

“Do you read to your kids at night?” she asked when the session finally ended. The question stung me. I worked and I drank. I had more important things to do than read to my kids. Yet, in that moment, with that simple question, I realized who I had become.

I looked her straight in the eye and lied: “Of course.”

♦◊♦

The next week, she had be bring a few of my kids’ books. I searched my 2-year-old daughter’s bedroom and found three Dr. Seuss books: Go, Dog, Go!, There’s a Wocket in my Pocket!, and Oh, the Places You’ll Go! I volunteered to read to her at bedtime a few times, to practice for my next lesson—and because I knew it was the right thing to do as a dad.

A week later, I was at the same lectern trying desperately to spit out the words. “Big dog, little dog …”

I paused, letting a little air into my lungs, before reading the next line. It didn’t work. I still found myself struggling for breath, eventually having to stop and gasp. “Tom, you are exceptionally smart,” my drama professor said from the back of the room. “You make logical jumps without knowing it—you go straight from A to C. But when you are acting or speaking to a crowd, you have to slow your brain down so your mouth can keep up. Think A-B-C.”

I read again, looking for periods and commas to collect myself. “A little better,” she said. “Now, I want you to stand tall, drop your shoulders, and take on the voice and mannerisms of your favorite character.” I followed her instructions and read my Dr. Seuss script with passion and a heavy dose of overacting, trying to ham out each line as much as I could. She loved it. “Your assignment is to read just like that to your kids every chance you get,” she said. “Find that voice and project.”

♦◊♦

Back down the hill, the Providence Journal had been headquartered at 75 Fountain Street for nearly 200 years. The board met in a windowless, wood-paneled room. The aroma of pipe smoke was permanently in the air, the arms of the wooden chairs worn down by generations of use. This was no place for a boy. A massive mahogany table swallowed up the room, and portraits of former distinguished CEOs hung from the walls.

Steve, the chairman and publisher, sat at the head of the table. His board members sat in order of length of service. I was the farthest away. Steve called the meeting to order, dispensed with administrative items, and then turned to me for my financial review. All those older men focused their attention on the kid in the cheap seat. In the moment of transition from Steve to me, there was silence; skepticism filled the air. My blue suit, red tie, and new glasses couldn’t hide how out of place I was.

I took a deep breath in and exhaled. My diaphragm muscles worked just like my instructor said they would. I felt the air travel in and out of my lungs. I wasn’t holding my breath.

I imagined myself reading Go, Dog, Go! to my children.

“Thanks, Steve,” I said with a comfortable but serious smile. ”It was actually a very positive quarter financially for the Providence Journal.” I stopped and took another breath, in and out. The board wanted to hear what I was going to say next. I had them interested.

♦◊♦

Little did I know, less than a year later I would take the Journal public, play a key role in selling it, get kicked out of the house for being a drunk, and again be in need of my newly acquired public-speaking techniques: this time talking not about dollars and cents, but about the truth of my life as I got sober. And then, a decade later, traveling across the country speaking about the Good Men Project.

Even today, whether in a prison or at a screening in Hollywood, I still try to remember when I take the stage that it’s impossible to speak and hold my breath at the same time. And when I step down from the podium, I always tell myself, “I meant what I said, and I said what I meant,” adding, as only Dr. Seuss could, “and an elephant’s faithful, 100 percent.”

For more of Tom's works, as well as other pieces on related topics, go to The Good Men Project Magazine online, here.

Related Articles

- Good is Good: Men, Women, & Facebook

- Good is Good: The Superhero Myth

- Good is Good: Are Men Inherently Violent?

- Good is Good: Best Moment of the Day

- Good is Good: Men, Faith and Goodness